Article written by Lani DuFresne, 2018 BRIT Herbarium and Research Intern and student at Rice University.

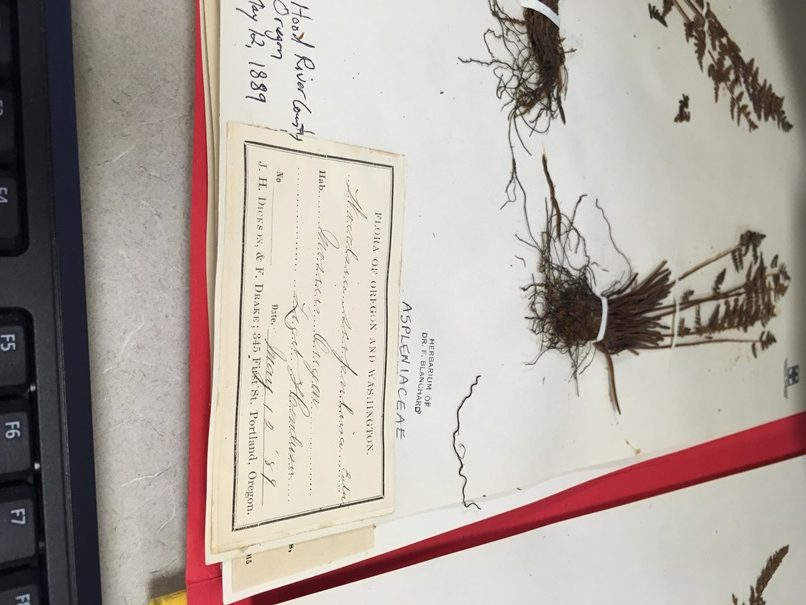

Out of everything I’ve learned so far in my education, cursive was one of the few skills I expected I’d never use. And yet, as I spent part of my summer trying to decipher the hastily scrawled, elaborate handwritten script a botanist from the 1880’s used in his collection notes, I found myself unexpectedly grateful for it.

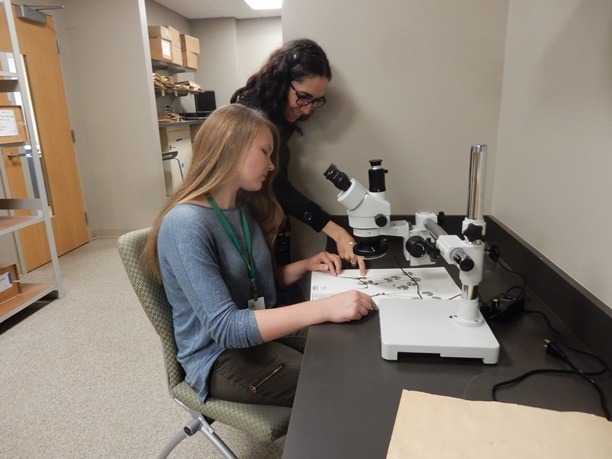

In all fairness, nothing else I did that summer was a task I would have expected to come across during my internship at BRIT with Dr. Alejandra Vasco, an expert on ferns. I participated in a project that aims to understand the history, distribution, diversity, and conservation challenges of native ferns in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex. On that morning in June I was trying to read handwriting from over a hundred years ago so that I could determine where this botanist had collected the fern in question – a dried, pressed specimen that had surprisingly withstood the test of time as well as his writing had. Once I had the location I could transcribe that information into a web portal called TORCH (the Texas Oklahoma Regional Consortium of Herbaria) that would share the record with anyone who searched for it. I was copying this information off of the collection label on the mounted specimen, which had been pressed, mounted, and labeled over a hundred years ago, and filed in multiple herbarium cabinets since then. In the span of a few hours, I had dealt with the processes of collecting, recording, mounting, filing, transcribing, and digitizing – all of which are crucial to research in the botanical sciences, and none of which I had known much about previously.

Even more astonishing was the timeframe of the work I was doing – the fern had been collected in 1889, mounted and shipped to a herbarium, filed away, and then transferred between herbaria and viewed by various experts over the span of decades. And now, in 2018, I was transferring the information to an online system making that record available to millions of people so instantaneously that no one in the 1880s would ever have dreamed of the possibility. But this is the reality of herbarium work: it is ever moving forward, advancing to the next level of accessibility while maintaining its permanent, growing collection of data for the use of all scientists.

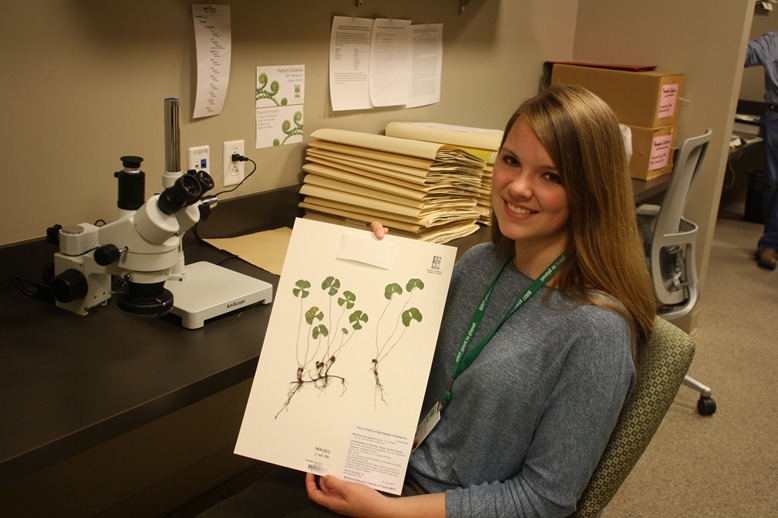

Reviewing the ferns that had been collected over a century ago left me with a sense of reverence; I was handling the expertly preserved specimen of a botanist who had long preceded me and whose work may outlast my own. Surprisingly, I found the same kind of awe while making my own first fern collection and one from the BRIT parking lot no less! I was now following the same steps collectors long before me had. I’d carefully collected as much of the plant and its reproductive structures as possible, pressed them between newspapers and cardboard, then packed them into a wooden press and shut them into a heater to dry out. From there they migrated to the freezer, and then I set about the task of arranging and gluing the specimen onto cotton paper to best preserve it. With the use of a local flora published by BRIT — The Ferns and Lycophytes of Texas — I identified the collection as a big-foot water-clover fern, Marsilea macropoda! Pteridologists (scientists who study ferns) of the past had then simply filed their work away into the corresponding cabinet of a herbarium. The recent rise of digitization meant that instead I first detoured to image my specimen, uploaded it onto the TORCH database, and georeferenced the exact coordinates of its location.

My work now sat amongst that of botanists old and young, famous and obscure, professional and amateur. As insignificant as it seemed in comparison to the collections from decades ago, it can be of just as much use to any researcher looking for information. In this way, herbaria are crucial to botanical studies for their role in preserving this type of data and making it accessible to researchers, especially with new advancements in online databases like TORCH.

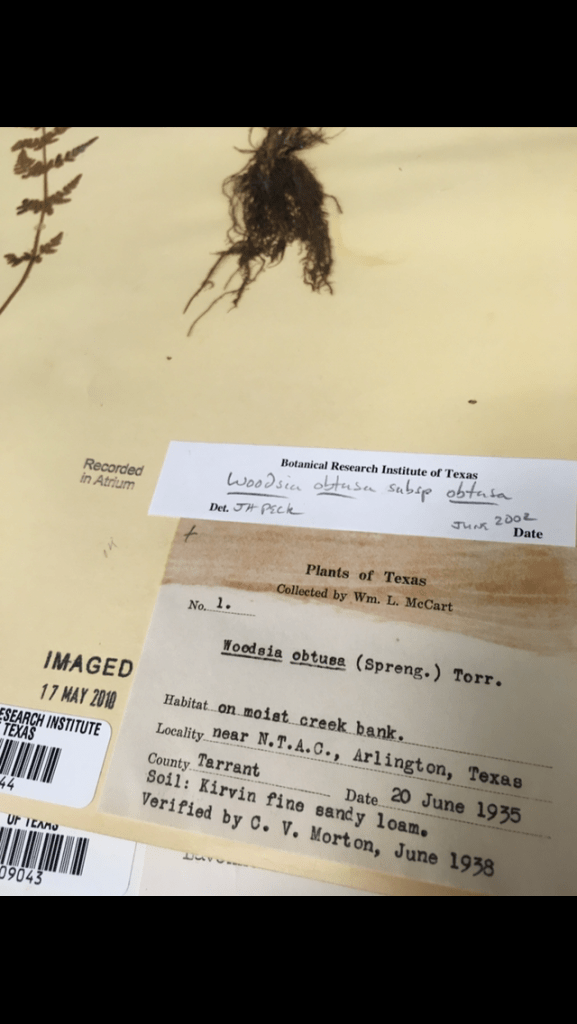

From all the Texas fern specimens I digitized this summer, I was shocked by one particular find: Woodsia obtusa, collection #1 from Wm. L. McCart in 1935. I later learned that McCart was a prolific collector with thousands of specimens to his name, and yet I’d managed to stumble across his very first collection. Clearly that fern had been only the beginning of a passionate career for McCart, and as I think about my own first collection, now sitting in the BRIT herbarium, I look forward to following in his footsteps.