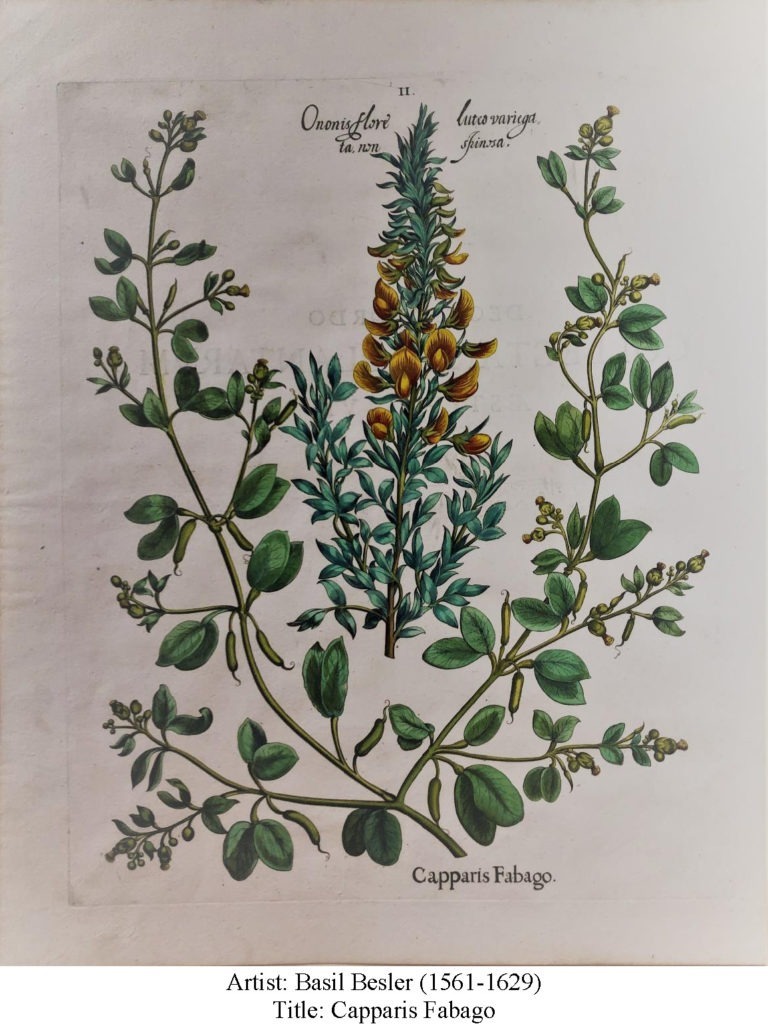

The history of civilization can be told through pictures of plants. The roots of botanical art and the science of botany began in ancient Greek and Roman times, depicting plants as a means of understanding and recording their potential uses. From the earliest medicinal plant books in the 1st century, through the first printed “herbal” around 1470, plants and nature slowly became depicted in a more realistic, accurate way. Today, we appreciate these illustrations’ beauty, but their real purpose was to provide reference for botanists. The scientific revolution in the 17th century gave way to discovery and exploration around the world, and botanists commissioned drawings of these curiosities that demanded a higher standard than found in most early books. The golden age of botanical exploration, discovery, and illustration was from the mid-1700s to the late 1800s.

Botanical illustration is still a vital part of the scientific discovery process today, and it is important in conveying information about plants. Art engages, attracts, and unifies people, increases plant awareness and appreciation, and builds consensus on the importance of preserving our natural world. The BRIT Arader Natural History Collection of Art now stands at 1,661 pieces and is an astonishing visual record of exploration of the natural world spanning four centuries.

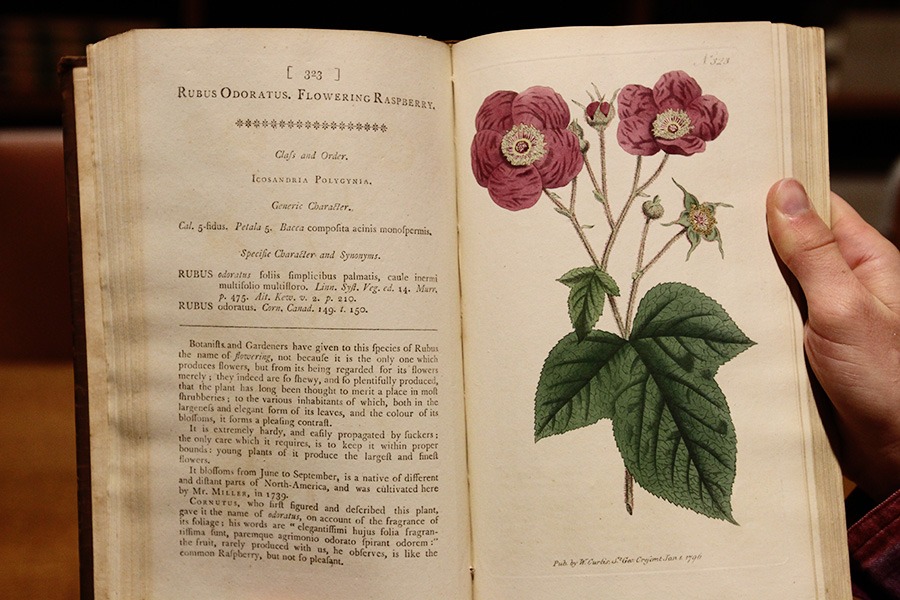

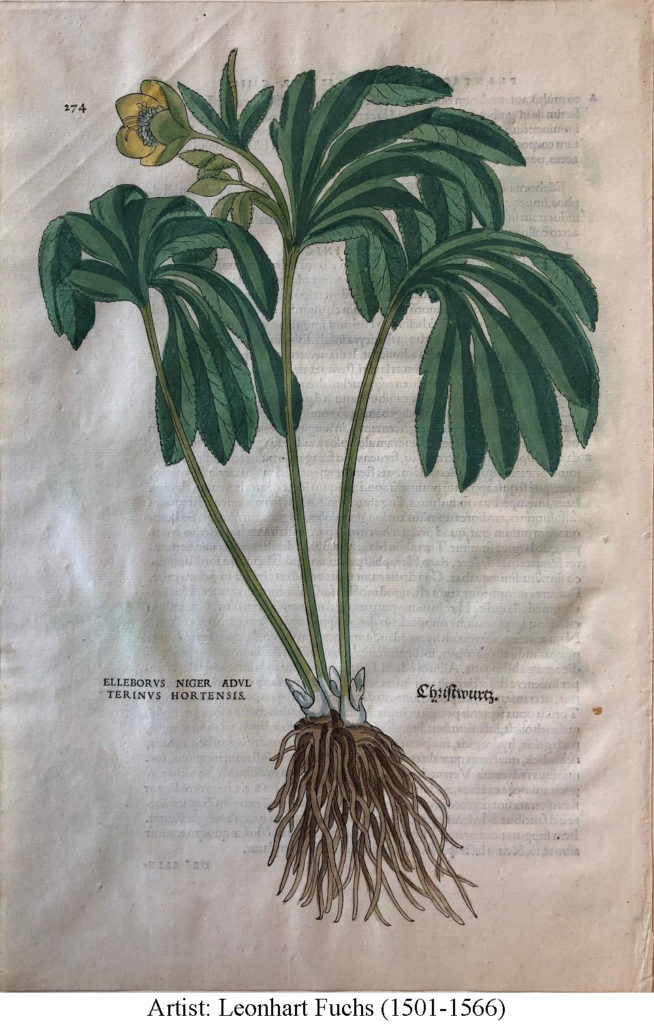

The earliest botanical illustrations at BRIT are the hand-colored, woodcut engravings from a large “herbal” (a book about plants and their uses in medicine). This book, first published in 1542 in Latin, is by Leonhart Fuchs, the great German physician and botanist (aka “herbalist”). The illustrations in Fuchs’ herbal represent a notable advance over its predecessors. The accurate and detailed drawings are really the beginnings of modern botanical drawing and had a far-reaching influence on botanical illustration for many years to come. These herbals and their illustrations of medicinal plants were significant early on in spreading information about plants. Despite its merits as an art form, botanical illustration is mainly an aid to science, and this generally means pictures in books rather than pictures on walls. In short, the science of botany depends not on original drawings but on printed illustrations, which is what is in the BRIT Arader Natural History Collection of Art!

Including line drawings/illustrations of each species known from East Texas are a vital part of the Illustrated Flora of East Texas project. Of particular importance for non-botanists is the inclusion of artwork for each species to aid identification. If you can draw and would like to contribute to science and the Illustrated Flora of East Texas, please contact Barney Lipscomb at barney@brit.org.

Research Team

-

Director of BRIT Press and Library, Leonhardt Chair of Texas Botany