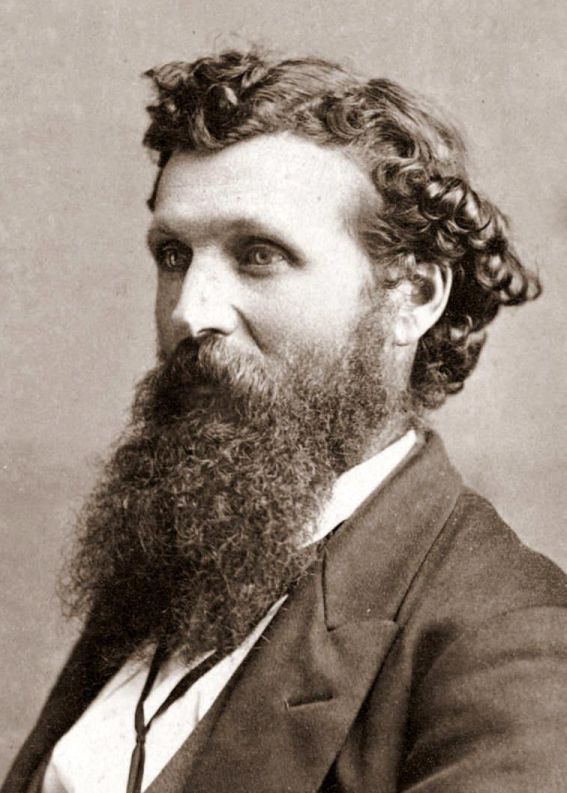

It was 1875, and John Muir was a busy man. He was already well-known for his journeys through central and northern California. His writing was published in newspapers and magazines around the country. But he still had time to help someone else.

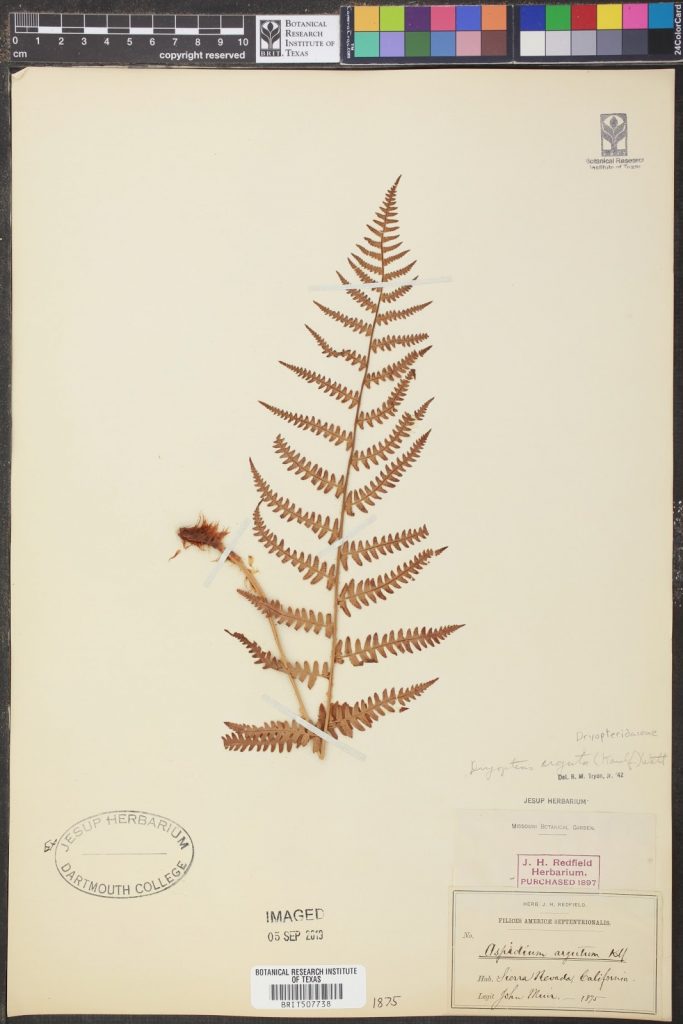

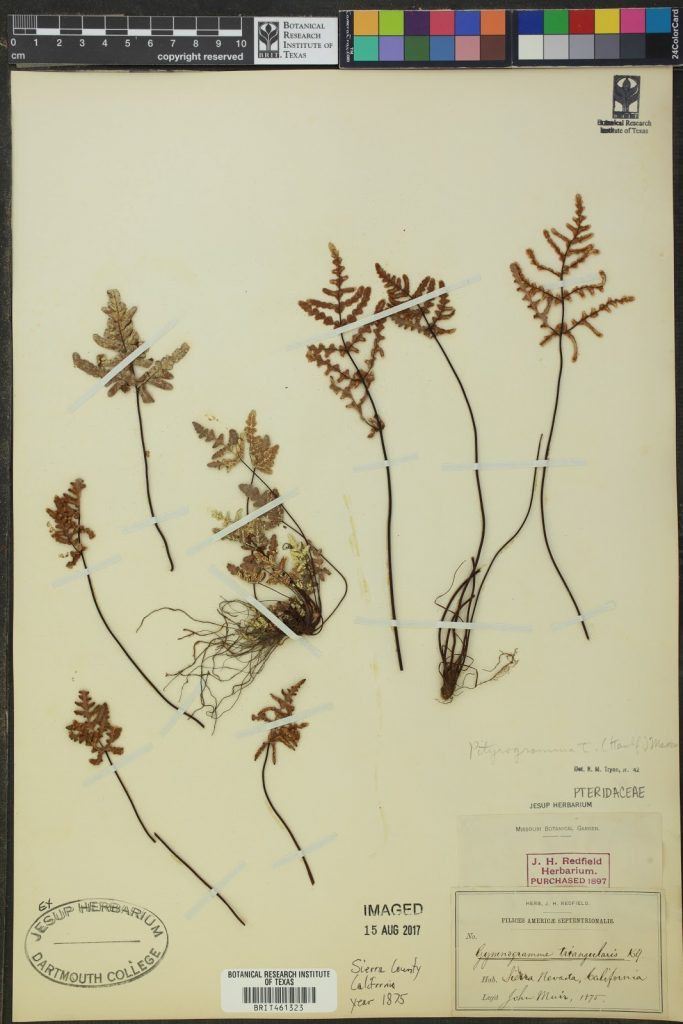

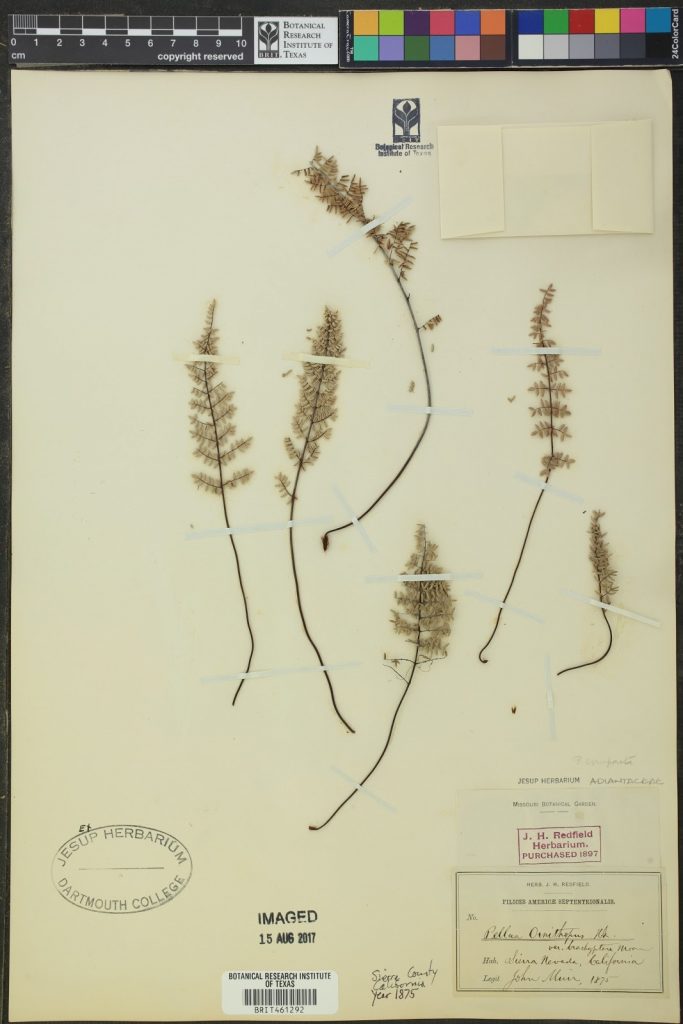

A colleague, John Redfield, wrote to Muir asking for specimens to add to his collection. John Muir wrote back in May of 1875 and promised to collect in a few weeks. True to his word, Muir collected plant specimens in the Sierra Nevada mountain range and sent them to Redfield for study later that year. They continued to correspond about the collections and other scientific pursuits for the next few years.

John Muir went on to campaign for the protection of natural areas. He wrote several articles and a few books describing natural areas and the wonders they contain. His efforts resulted in the creation of Yosemite National Park in 1890. For this achievement, he has been called “The Father of our National Parks”. In 1892, he co-founded the Sierra Club, an environmental organization that works to conserve natural resources and encourage people’s enjoyment of them. In his later years, John Muir traveled the world, taking part in expeditions north to Alaska, south to Brazil and Chile, and east to Africa. He worked for the conservation and appreciation of nature until his death in 1914.

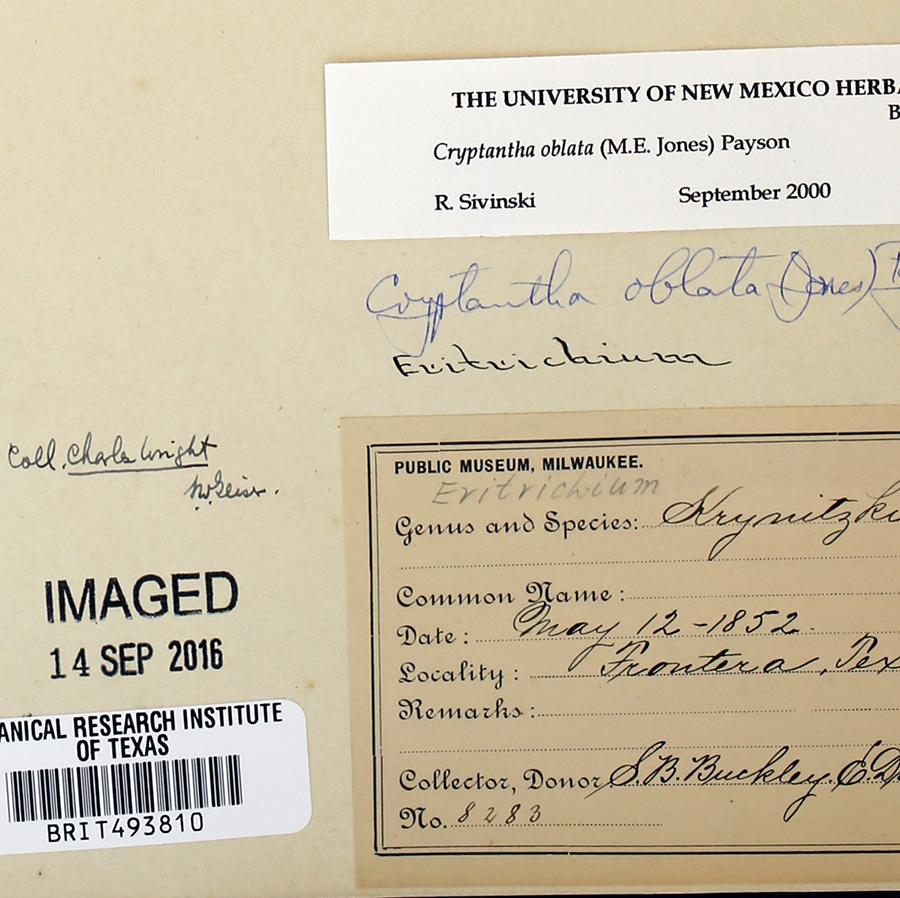

John Muir traveled extensively during his life, and the plants Muir collected went on a journey of their own. In 1875, the collections were sent to Redfield’s herbarium in Philadelphia. Twenty-two years later, in 1897, Redfield’s herbarium was purchased by Missouri Botanical Garden, and the plants were sent to St. Louis, Missouri. The collections stayed at Missouri for an unknown amount of time before they were sent to the Jesup Herbarium at Dartmouth College, probably in a shipment of specimens for exchange. The specimens stayed at Dartmouth College until 2002, when the Jesup Herbarium distributed a large portion of its holdings to other herbaria. BRIT received about 25,000 specimens from the Jesup Herbarium, these Muir fern specimens among them. That’s over 6,000 miles that these specimens traveled, a long way to go for plants that usually stay rooted in one spot! Since then, they have rested in our storage, undiscovered until recently, when a grant from the National Science Foundation gave us the ability to digitize our fern collection. This discovery underscores the importance of digitizing biocollections, as we can never completely know a collection until it is searchable in a database.

To see more of our digitized specimens, and maybe discover a few hidden treasures of your own, check out our Armchair Botanist program.

This fern work is part of National Science Foundation’s Advancing Digitization of Biological Collections (ADBC) program, grant number 1802270. Access the specimens digitized by the Pteridophytes Collections Consortium TCN here: http://www.pteridoportal.org/portal/.

Sources

- https://vault.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit/life/chronology.aspx

- https://discoverandshare.org/2019/04/18/collection-connection-john-muir-herbarium/

This post is part of our “Cabinet Curiosities” series that explores significant items from the Herbarium collection. Posts are written by staff, volunteers, and interns. Read more from the series here.