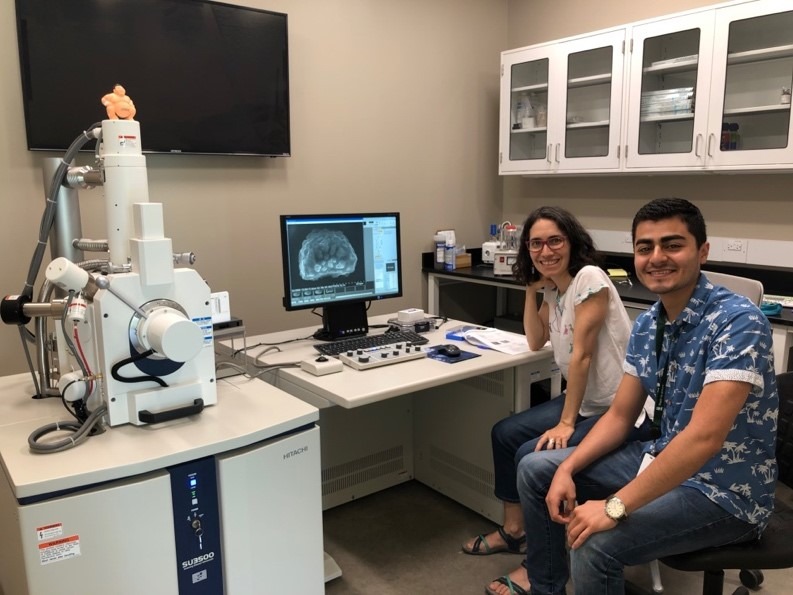

This article was written by Ivan Rosales, 2019 BRIT Summer Intern and student at University of Texas at Arlington. Ivan interned with Dr. Alejandra Vasco, working on fern diversity and anatomy.

Who Would Have Thought to Look?

The Micromorphology of DFW Metroplex Fern and Lycophyte Spores

Anthony van Leeuwenhoek was a scientist from the Netherlands who discovered and described for the first-time bacteria, microscopic protists, sperm cells, blood cells, microscopic nematodes, rotifers, and much more. Even centuries after Leeuwenhoek first looked at a drop of pond water through his early microscope invention and saw microscopic creatures, people still asked, “Who would have thought to look?” I asked myself the same question after seeing my first mounted fern spore using BRIT’s Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) at the George C. and Sue W. Sumner Molecular and Structural Laboratory.

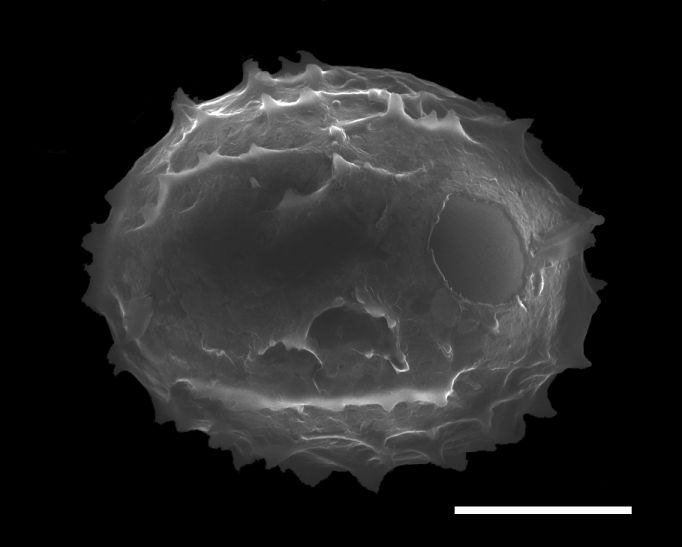

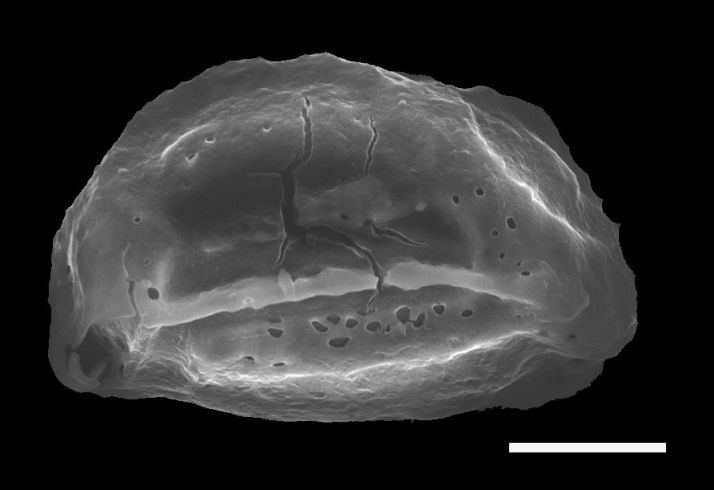

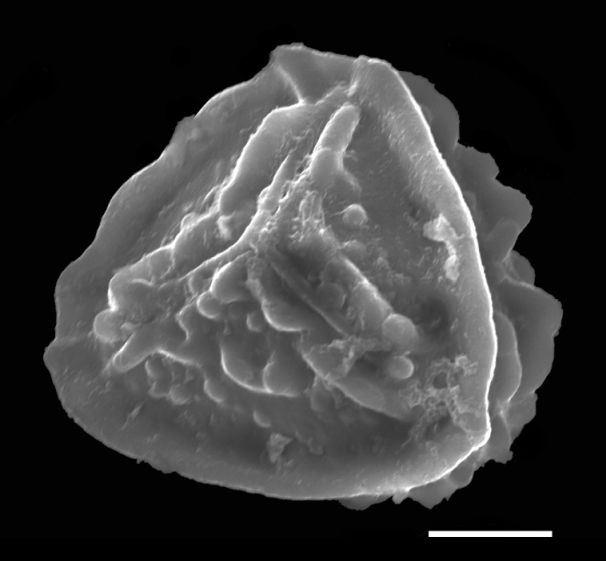

This summer during my internship at BRIT I worked with an avid fern expert, Dr. Alejandra Vasco, constructing a collection of SEM photographs of the spores of the fern and lycophyte species native to the DFW Metroplex. These spores can hardly be seen with the naked eye but have very interesting appearances when seen using a powerful microscope. The SEM is a very powerful tool in research, that can be used to view things unimaginably small. It uses an electron beam against what you want to see, in this case spores, and the image seen on the computer screen, rather than through a lens, is simply the electrons reflecting off it.

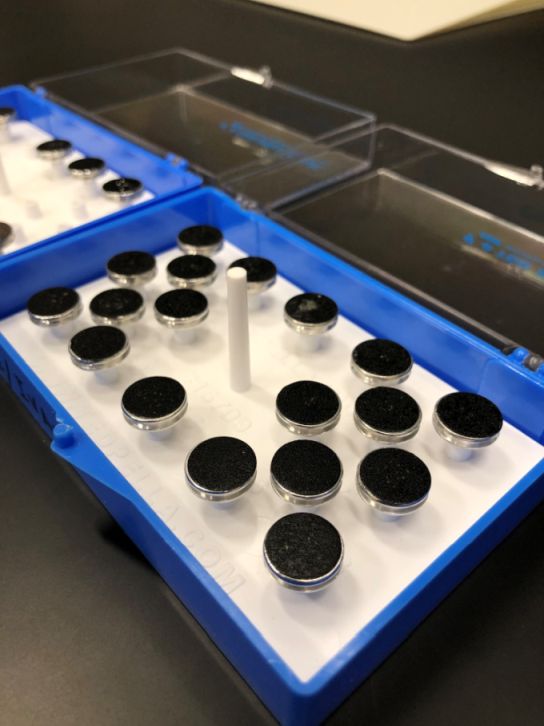

But, how do you prepare spores before they can be imaged? First you have to find spores! Ferns are quite different compared to the plants most people are used to seeing in that they disperse using spores and have no flowers or seeds. Fern spores can be found in the undersurface of the leaves inside small capsules called sporangia, that when fresh look like caviar. Spores can be found in live plants or herbarium specimens and for my project I used the collections deposited in the BRIT herbarium. I first pulled out all fern and lycophyte collections belonging to the DFW metroplex. Then, using a dissecting microscope, I removed 3-4 sporangia from some specimens and mounted them onto 15 mm SEM pins with double side carbon tape. I then carefully opened the sporangia with a dissecting needle and spread the spores on the tape. After that the spores are ready for viewing. The pin with spores is placed inside the viewing chamber of the SEM, air is evacuated from the chamber, and the specimen is ready for observation. Multiple parameters are then assiduously adjusted for the best image.

One would imagine that spores are perfectly round and smooth with very few surface features. However, during my internship I gained an appreciation for the complexity of plants after seeing how much there is to learn about these microscopic fern spores. Using the SEM was a very enthralling experience because of how powerful it is for capturing images with great detail. Much like with Leeuwenhoek’s observation of pond water hundreds of years ago, I ask myself the same question about these fern spores: “Who would have thought to look?”