This article originally appeared in BRIT’s former newsletter publication, Iridos, Issue 20(2) 2009.

“Hell — is sitting on a hot stone reading your own scientific publications.” ~ Erik Ursin, fish biologist (in Sand-Jensen 2007)

One of my favorite journal articles is a little number called “How to write consistently boring scientific literature” (Oikos 116:723–727. 2007). Penned by Kaj Sand-Jensen at the University of Copenhagen, this piece is a glib editorial about technical writing…that was somehow published and promulgated by a technical writing source. (Brilliant!)

Sand-Jensen complains that current science has lost its charm in recent years, dispensed with its sense of humor. We used to write with flavor, he says, with life. Not anymore. Somewhere along the line, colloquialisms became a no-no. “Unprofessional!” we were told. And now dry and lifeless prose is the norm.

But a pocket of resistance has survived, souls and humor intact, and some of these are the authors who contribute to Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas. Looking back through the archives of the journal one finds papers whose titles exude life and character, often sprinkled in among the less lively. In fact, non-boring titles are the cleverest of all guerrilla tactics in the anti-yawn movement because, really, what is a title? What does a title actually do?

Well, in the broadest sense, titles are everything. They set the tone. They underscore the message, the emphasis of the paper. They are the worm, dangling there on top of it all, hoping to ensnare a big, juicy, literate fish. They are the first impression! And good titles, most likely, speak to the cleverness of article contents.

But titles are also harshly scrutinized. They are often listed in multiple publications, both print and online, and are therefore subject to the rigors of public relations standards and judgment.

But if an author is clever enough, he can still show his feelings, his humor, and a bit something more than just words on paper. Through a carefully crafted title, a writer can summarize both his intent and his opinion in a mere line or two.

At times, all it takes to spice things up is well-placed punctuation. (Consider “Nicolletia occidentalis in Baja California!” or “A cypress in Jeff Davis County, Texas?”.) Aiming carefully, an author can then follow up former titles and play off his own riffs (“Another juniper in Jeff Davis County, Texas? We’re not convinced”). Simple alliteration will often improve an otherwise stuffy subject (“Published illustrations of Penstemon hirsutus: magnificence, malformation and misidentification”). Other times, a subtle confrontational note can be the hook that grabs (“Orthodon vs. Mosla”…this time it’s personal).

A title can show mere confusion (“Thomas, Townsend, or Townshend—What was T.S. Brandegge’s name?”) or outright despair (“What is the writer of a flora to do?”). It can be grandiose in scope (“Amur honeysuckle: its ascent, decline, and fall”), apocryphal (“The impending naturalization of Pistacia chinensis in East Texas”), or even biblical (“Commandments for communication”). Titles can contribute some literary philosophy (“The Gerbera complex: to split or not to split”) or esoterica (“Cuscuta—the strength of weakness”). Poetry, though rare, is greatly appreciated (“By any other name…”). And, just as with everything else in this modern world, sex sells (“Sex and the angiosperms—another proposition”).

Now, be honest. Did any of the above titles make you curious as to the contents of the rest of the paper? I’m guessing that most of you answered “Yes” even if somewhat begrudgingly. But that’s good! This means that the efforts of the guerrilla science writer are not in vain.

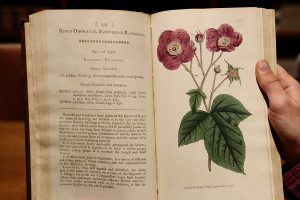

If you’re really curious and want more title excitement, you can go here and click on “Biodiversity Heritage Library.” The title is just the beginning. Imagine what awaits!