Texas is home to 448 rare vascular plant species, including 113 species categorized by NatureServe as Critically Imperiled (G1) and at high risk for extinction. For many of these species only a handful of individual plants remain in the wild. These plants are faced with increasing levels of threats, with population growth and the resulting development, land use changes, invasive species, and now climate change all threatening to push our rarest species closer to extinction. While conservation of a species within its natural habitat is the ultimate goal for plant conservationists, this approach is not always possible. Seed collections serve as a powerful tool in preventing extinction by serving as a genetic backup that can be used to repopulate a lost population.

Seeds serve as source material for research on rare species, but more importantly, they serve as a source for the reintroduction of plants into the wild. Catastrophic events, such as Hurricane Harvey in 2017, have the potential to completely eradicate entire populations of plants, especially in the case of extremely rare plants, where a single wild population may be all that stands between the plant and extinction. Seeds stored in a conservation seed bank can provide a source to repopulate lost populations and prevent a plant from becoming extinct.

Why seed banking?

Seed banks have several advantages as a technique for protecting rare plants. A large quantity of seeds can be stored in a relatively small space; thousands of seeds can be housed in a laboratory freezer that takes up no more room than a home refrigerator. Yet within this modest space researchers can ensure the plant’s future health by protecting the genetic diversity of the species.

Modern seed banks date back to the 1960s and 1970s, as plant researchers recognized threats to plants and sought to preserve their diversity. Seed banking takes a variety of forms across the globe. Some of the most well-known seed banks focus on plants in agricultural use; the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, built into a mountainside in Norway, for example, stores seeds from important food crops such as wheat, maize, potatoes, and rice. The Millennium Seed Bank of Kew Gardens in the U.K. has the most ambitious goal of any seed bank, seeking to store every plant seed possible; it anticipates reaching the milestone of banking 25 percent of the world plant species by 2020.

The BRIT Seed Bank opened in Fall of 2019 and focuses on the preservation of rare and threatened native plants, particularly those that grow right here in Texas.

Conservation partnerships

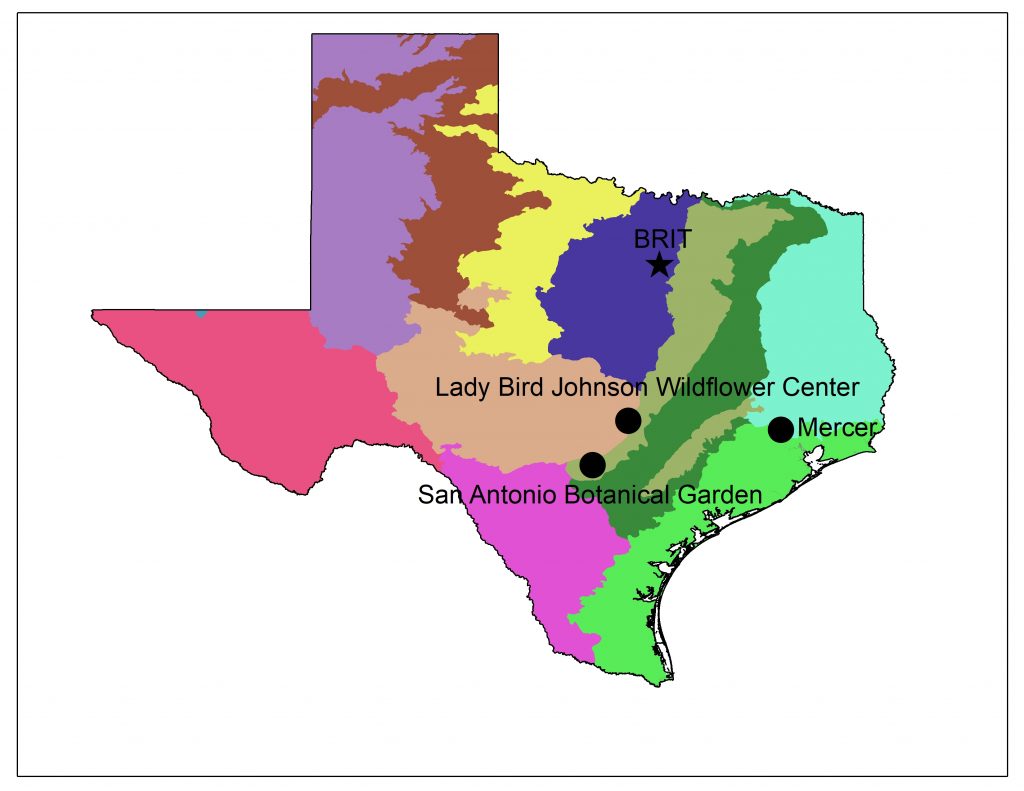

Researchers worldwide recognize the critical role seed banks play in preserving rare plants. Several organizations in Texas preserve seeds, including the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, Houston’s Mercer Botanic Gardens, and the San Antonio Botanical Garden. But Texas is so large and has so many rare plants, it’s difficult for any single organization to protect all of the state’s plant diversity. Furthermore, the more institutions storing the seeds of rare plants the better. The greater the number and variety of protected seeds, the better the chance of eventually reestablishing plants in the wild. BRIT joins the three existing conservation seed banks as a participating member of the Center for Plant Conservation (CPC). The four Texas members of the CPC have the joint responsibility to protect the rare plants of Texas. With almost 450 taxa at risk of extinction within the state and only 80 plants effectively conserved, there is a lot of work left to do.

Why are native plants at risk of extinction?

Numerous forces threaten native plants:

- Habitat destruction. Habitats can be destroyed by development, road construction, or any other change to land use.

- Invasive species. Plants not native to a region can sometimes overtake the habitats of local plants and force them to extinction. In Texas, numerous exotic plants, including salt cedar, Chinaberry, privet, and giant reed, often force out native species.

- Wild fires and fire suppression. Fire can be devastating to plants with isolated populations. At the same time, fire suppression efforts can also harm native plants that evolved to live in habitats regularly cleared by fire. Native grasslands, savannahs, and open woodlands can become overgrown with thickets of wooded species that drive out native plants.

- Climate shifts. Texas is experiencing shifts in temperature levels and rainfall patterns that are transforming local habitats. Some plants struggle to adapt to changing conditions and die out when their habitats change.

While these are the most common threats, other native Texas plants face unique pressures. Texas wild rice, for example, grows in a single mile-and-a-half stretch of the San Marcos River, within the city limits of San Marcos. The plant is endangered by development, recreational use of the river, and non-native plant and animal species. Hundreds of miles away in Big Bend National Park, cacti are threatened by poachers who trek deep into the desert to remove rare species to sell to collectors.

These unusual circumstances demand creative conservative strategies and often the cooperation of numerous local, state, and federal agencies. But no matter the unique pressures on native plants, seed banking can be an important tool in protecting the species.

How seed banks save rare plants: the importance of genetic diversity

Seed banks are one of multiple strategies conservationists employ to protect plants. One option is to sustain the plant in its native habitat, perhaps by partnering with land owners or state agencies to monitor and protect the plant. However, small, isolated populations can be difficult to maintain, and more intensive conservation strategies might be necessary to save the species.

Another option is to grow at-risk plants in a botanical garden. However, gardens have limitations—space, for one thing. Only so many plants can be grown within a garden, and this limits the genetic diversity of the plant population. Preserving the genetic diversity of plants is important because genetic variability can help plants adapt to changing conditions, compete against invasive species, and withstand threats such as pathogens. Genetic diversity is necessary to keep plant populations healthy.

Preserving genetic diversity in a botanical garden becomes particularly challenging when protecting large plants, such as giant cacti or large trees. It’s easy to grow several hundred wildflowers in a garden; it’s incredibly difficult to establish a forest of threatened tree species. On the other hand, hundreds of seeds from hundreds of parent plants, with all their genetic variability, can be stored in a single zip-top baggie. Seed banks are a highly efficient way to preserve diversity.

Seed banking 101

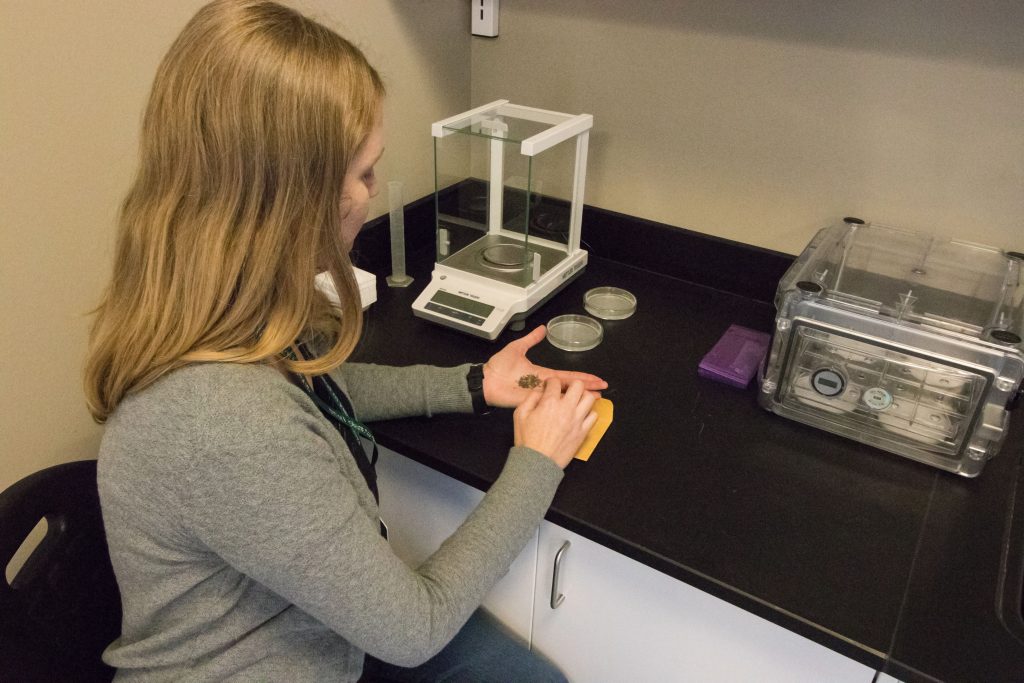

For the majority of plants, seed banking is a relatively simple process. Seeds are collected in the field, then brought back to the lab to be cleaned, dried, and preserved. Generally, seeds are then stored in a freezer at minus 14 degrees Celsius.

Some seeds, however, do not thrive under this standard protocol. It is estimated that about 90% of the rare plants in Texas are considered “orthodox” and can be stored using the standard protocol. A small percentage of seeds however, will not germinate if they are dried and frozen. The most well-known among these so-called “recalcitrant” seeds are the acorns of many oaks.

If scientists are uncertain how a particular seed will react to freezing, they must test samples and find the best preservation method for each seed. Some recalcitrant seeds, for example, can be flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen in what is called cryopreservation.

As a seed bank collection grows, work with the seeds doesn’t slow down. Researchers trade seeds with other organizations, work with conservationists on repopulation efforts, and conduct genetic research on the plants. Seeds are tested regularly to ensure they are still viable.