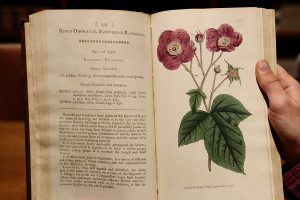

In our year-long “Hidden Treasures” series, Alyssa B. Young, Special Collections Librarian, features notable works in the BRIT rare book collection.

This is the second blog post about Alexander von Humboldt. Because he’s just too interesting! Our first post concentrated on his 1799-1804 South American expedition and a resulting book that is housed in our rare book collection. Click here to read that article.

You’ve likely heard the name “Humboldt” before. You might know of the Humboldt Current, which flows along the west coast of South America. California, Iowa, and Nevada all host a Humboldt County, and the latter state was nearly named Humboldt! How does a trip to “Las Vegas, Humboldt” sound?

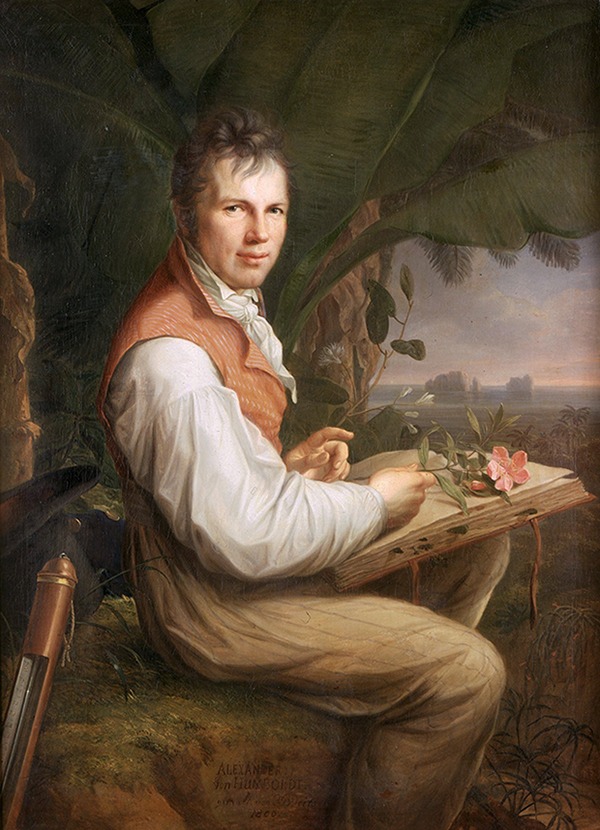

But you likely don’t know much about the man behind the name, Alexander von Humboldt. More species and places are named after Humboldt than after any other human being. The story of his life is one of dedication and exploration. Humboldt was a true man of the Enlightenment, diving hard into all subjects that passed before him, pushing his body to the limit in the pursuit of knowledge. He worked late hours, took on dangerous expeditions, and his health often suffered as a result of his relentless passion towards learning. Throughout his life, Humboldt made significant contributions to a wide array of scientific fields, including botany, zoology, electrophysiology, oceanography, geology, climatology, magnetism, meteorology, astronomy, and mineralogy.

Yes, you read that right. He made significant contributions to each one of those vastly different scientific fields!

Alexander von Humboldt was born in 1769 to a wealthy family in Prussia. He was drawn to science at an early age, collecting thousands of plant specimens and insects near his home. Much to the chagrin of his mother, who wished him to pursue a career in civil service, Humboldt dreamt of being a scientific explorer. After attending university and a prestigious mining academy, the young Humboldt proved a very successful mine inspector. This job satisfied his mother’s wishes for him and allowed him to explore his interests in geology. He had a ferocious work ethic when studying science and even completed his difficult mining courses in 8 months, as compared to the average student’s 3 years. He spent his spare time collecting thousands of botanical specimens from mines to study the influence of light, writing and reading until late into the night.

Humboldt transformed the way naturalists and scientists had viewed nature for millennia. His studies expanded far beyond botany. In studying the natural world, he sought to gain an “impression of the whole” rather than focus on the small details. By studying different scientific principles, he saw the earth as a living organism. Whereas previous philosophers had viewed the earth simply as a resource created for man to use, Humboldt suggested it was full of connections and vulnerable to destruction: “In this great chain of cause and effects… no single fact can be considered in isolation.” Yep, he was the first to propose the idea of ecosystems.

Studying plants and their interactions with their surroundings led him to discover many more ideas that are integral to our work today, including man-made climate change, climate zones, use of guano as fertilizer, and the idea that South America and Africa were once connected. Such ideas are staples of the way we view nature now, but they were innovative and radical at the time. Humboldt’s expansive discoveries and theories provide the basis of numerous scientific fields – so much so that his naturalist prowess has been overlooked in many ways.

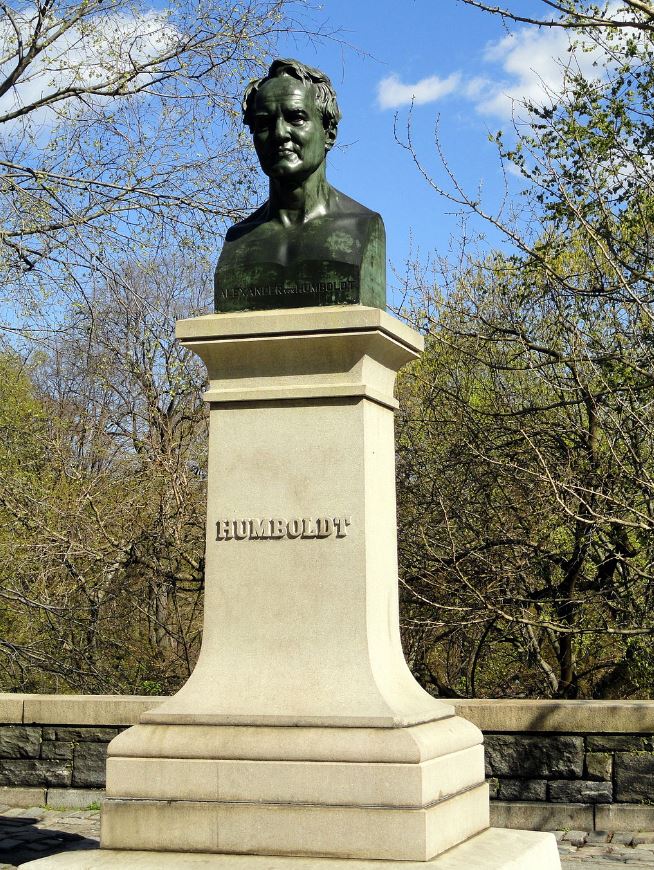

Things weren’t always such, though. Once upon a time, Humboldt was the most celebrated naturalist in the world. On September 14, 1849, the centennial of his birth, New York City hosted a festive parade, concluding in 25,000 people watching the unveiling of his bronze bust in Central Park. This day was celebrated nationally and globally, with parties stretching from San Francisco to Australia to Egypt to Russia. He was lauded as the “Shakespeare of sciences.” Isn’t that poetic?

So why in the last 150 years have we forgotten about him? As The Invention of Nature author Andrea Wulf summarizes, “Humboldt gave us our concept of nature itself. The irony is that Humboldt’s views have become so self-evident that we have largely forgotten the man behind them.”

Humboldt’s expansive contributions to natural history inspired the works of a great number of scientists, as diverse as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Thomas Jefferson, John Muir, Albert Einstein, Edgar Allen Poe, Walt Whitman, Henry David Thoreau, Jules Verne, Simon Bolivar, and Charles Darwin. Read through that list again, and think of all the different ways these men contributed to our world.

In the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Humboldt was one of those wonders of the world, like Aristotle, like Julius Cæsar, like the Admirable Crichton, who appear from time to time, as if to show us the possibilities of the human mind, the force and the range of the faculties…”

How’s that for a legacy?