Our hot, dry summer continues, and humans aren’t the only ones struggling. Plants suffer, too. All around North Texas, you’ll find brown lawns, withered shrubs, flattened flowers and drooping trees.

Yet some plants thrive despite the persistent 100-degree-plus temperatures–even without supplemental water. What’s their secret? How have plants adapted to hot, dry conditions–and what happens when they reach the limit of their endurance?

Survival strategies

Heat and drought pose serious challenges for plants. In general, actively growing plant tissue cannot survive temperatures greater than 113 degrees Fahrenheit. (The exceptions are some desert grasses, cacti and agaves.) Under high heat conditions, it becomes increasingly difficult for plants to photosynthesize light and to take in oxygen. Cell membranes become unstable. Proteins break down and enzymes become inactive.

These issues are compounded by lack of water. Water is necessary for every aspect of plant development, and without it, plants are unable to photosynthesize light or complete any other metabolic processes. The plant cannot grow new cells or transport necessary minerals. The plant will wilt, scorch, lose leaves and branches and eventually die.

Nevertheless, plants have found ways to adapt to high heat and low water conditions. Plants grow in the hottest and driest places on earth, including in Death Valley and surrounding the Dead Sea. How do they survive?

Different plants cope in different ways:

Wait for the best conditions. Many plants have evolved seeds that can tolerate the most extreme drought and heat. The seeds remain dormant until the right conditions present themselves–such as a sudden burst of rain. The Atacama Desert in Argentina and Chile is one of the driest regions of the world, second only to some valleys in Antarctica. These dry conditions have persisted since at least the 16th century and most likely thousands if not millions of years. Nevertheless, when rain does reach the Atacama, the hillsides burst into bloom as wildflowers suddenly spring to life. This pattern is repeated around the world and is sometimes known as a “superbloom.” Generally, these plants live fast and die young; they mature rapidly and produce as many seeds as possible while conditions remain in their favor, then vanish again.

Seek out microclimates. Even within the hottest, driest areas, small areas of shade and/or moisture can still be found. There are several types of microclimates. Oases, for example, form around sources of freshwater in otherwise dry locations. For example, where Havasu Creek joins the Colorado River, the bare rock of the Grand Canyon is hidden by an exuberant display of maidenhair ferns, wild grapes, rockdaisies, prickly pears, cottonwoods and desert willows. Some microclimates are truly tiny, as small as bit of ground under a rock. Tiny mosses have been discovered growing under chunks of milky quartz in the Mojave Desert.

Adapt to heat and drought. Plants have evolved multiple strategies to live through hot, dry conditions:

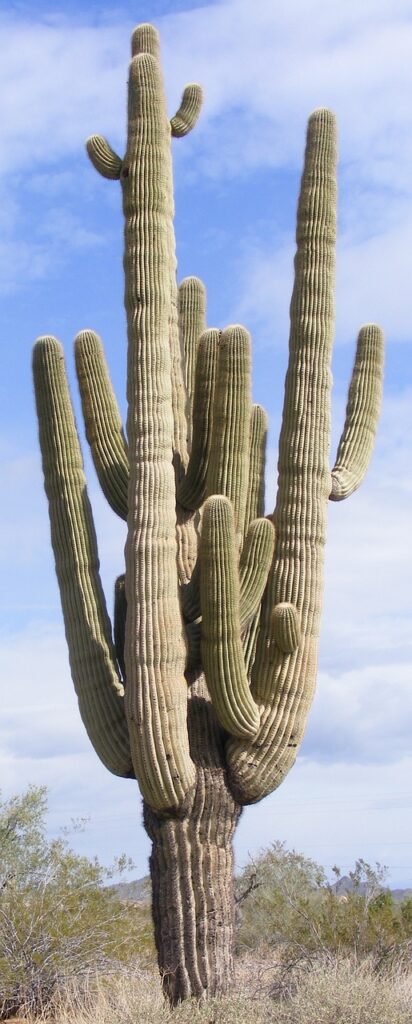

Succulents (including cacti and agaves) can absorb and store large quantities of water in short periods. Saguaro cacti can store up to 1,000 gallons of water in their trunks. This makes these plants targets of birds, animals and insects in search of water. Many cacti and agaves have developed spikes and thorns to protect their most precious resource.

Succulents have also developed a water-efficient photosynthesis process called CAM (Crassulacean Acid Metabolism) that significantly reduces water lost to evaporation and allows the plant to go into a dormant state when water is unavailable.

Non-succulent perennials known as xerophytes employ multiple methods of surviving drought. They have deep, extensive root systems that can find every drop of water in the soil and can photosynthesize with less water than most plants. For example, several species of mesquite have found to grow roots that reach nearly 160 feet deep.

Other strategies employed by desert plants include:

- A small surface area that limits water lost to evaporation. Plants might have small leaves, narrow leaves, or, in the case of cacti, no leaves at all.

- Reflective features such as light-colored leaves, waxes or hairs on the plant’s surface that help reflect light.

- Vertically oriented leaves that expose less surface area to the sun.

- Waxy surfaces that prevent evaporation.

Recent findings about how plants react to extreme conditions

The trend toward higher global temperatures has accelerated interest in how plants respond to drought and high temperatures. For example, a recent article in Annals of Botany described research on how wheat plants cope under extreme water stress. Wheat, they learned, prioritizes delivering water from the roots to the reproductive tissues over other parts of the plant, including leaves. This allows the plant to reproduce even when water is scarce.

Another recent article in the journal Cell looked at how plants react when experiencing stresses such as water deprivation or damage. The researchers found that tomato and tobacco plants under stress emit sounds comparable in volume to normal human conversation. Humans don’t hear the sounds because they are ultrasonic–that is, too high for our ears to detect.

The sounds, which have been described as rapid popping, could be detected more than a meter away. It is not yet clear exactly how the sounds are made, but there is no evidence that they are an intentional cry for help from the plant. One theory is that the pops might be due to air bubbles forming and bursting in the plant’s vascular system. Researchers have theorized that other plants or insects might have learned to react to the sounds, and studies are now underway to test this hypothesis.

Researchers also suggest the plant noises may have a practical use for humans. Distressed plants began emitting sounds began before any other signs of dehydration, such as browning leaves, appeared. Farmers might be able to monitor the thirst levels of plants and water them before further damage occurs.

If you have heaved a huge sigh when stepping outdoors or yelped when your hands touched a hot steering wheel, know that the plants of North Texas are likely making their own sounds of distress during the August heat. Until it passes, try to keep yourself and the plants you love hydrated until cooler fall weather comes again.