The new exhibit Dinosaurs Around the World: The Great Outdoors invites guests to discover hulking dinos in the landscape as you explore the Garden. But we can only go so far in evoking the deep past. The plants that surround our animatronic dinosaurs are not the same as those that lived millions of years ago—and there’s not much we can do about it.

That’s because when dinosaurs first walked the earth 250 to 200 million years ago, non-flowering plants dominated the planet. Today, flowering plants out-number non-flowering plants across the world—and in our Garden.

That means if you want to picture dinosaurs in their natural habitat, you have to remove from your mind’s eye every oak and pecan tree, every tulip and rose, every herb and grass. In their place, you need to imagine lots and lots of ferns.

Fortunately, the Garden has its very own a fern expert who can tell us everything we want to know about this fascinating form of plant life: Alejandra Vasco, a research botanist specializing in ferns and lycophytes. We turn to her to learn what ferns are and what makes them special. She also shares how considering the impact of the extinction of the dinosaurs on the planet can help us understand ecological change today.

Plant life in the age of the dinosaurs

The most common plants on earth today are flowering plants, known to botanists as angiosperms. All angiosperms produce seeds in flowers that contain plant sexual organs. All grasses, broad-leaf trees, shrubs, vines, aquatic plants and flowers are angiosperms.

The earliest angiosperms appeared about 145 to 100 million years ago (although some research points to earlier dates.) But angiosperms were the second type of plant life to cover the planet. Before the rise of angiosperms, ecosystems were dominated by non-flowering plants.

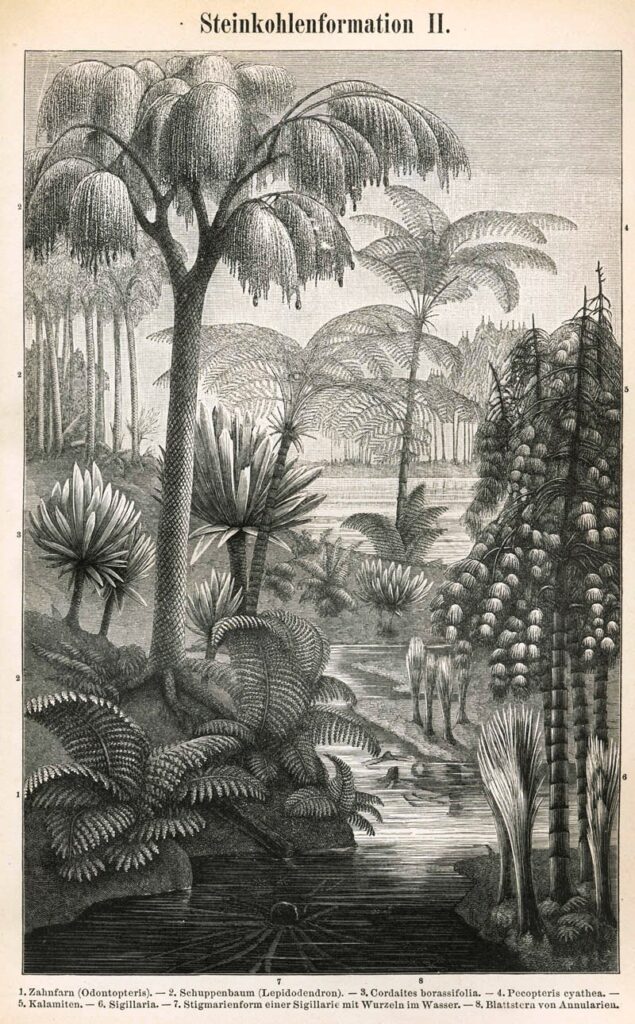

Non-flowering plants fall into several categories, including mosses, ferns, lycophytes and gymnosperms. Starting about 419 million years ago, these plants covered the planet’s landmasses, forming enormous forests dense with life.

Gymnosperms include conifers (such as cedars and firs) and ginkgos, of which the only surviving genus is the Gingko biloba tree. Lycophytes were also prolific. Today, most lycophyte species are small and unobtrusive clubmosses, spikemosses and quillworts. But 350 million years ago, some now-extinct lycophytes grew into trees more than 150 feet tall.

Ferns also played a major role in those ancient landscapes. Some ferns in the Carboniferous (358-298 million years ago) and Permian (299-251 million years ago) reached 50 feet tall. Vasco finds this era fascinating. “If I could go back in time, this is when I would go,” says Vasco. “I would love to see those incredible forests.”

During the Cretaceous Period (145-66 million years ago), the number of flowering plant species exploded, an event botanists call “the angiosperm radiation.” Flowering plants became so successful they came to dominate ecosystems, driving many species of non-flowering plants to extinction. Today flowering plant species outnumber non-flowering plant species twenty to one.The sudden rise of flowering plants so baffled Charles Darwin that he called it “an abominable mystery,” and exactly why and how it occurred remains unclear, although today biologists believe the simultaneous rise of pollinators may be part of the answer.

Nevertheless, ferns survived the angiosperm radiation and are still found around the world today.

What Makes a Fern a Fern: A Two-Generation Lifecycle

So, what are ferns? “What distinguishes ferns is their lifecycle,” says Vasco. This lifecycle can be divided into two separate phases or, more precisely, two generations.

If you envision a fern, you are picturing one phase of the fern lifecycle. The technical name for this generation of fern is sporophyte. The job of the sporophyte is to produce spores, which form in little bumps on the underside of fern fronds. (“Many people see these bumps and think they are a disease,” says Vasco.) When the spores are mature, the sporophyte ejects the spores into the wind.

It’s important to note that spores are not seeds. Each spore is a single cell. Seeds, on the other hand, are multicellular and include a fertilized plant embryo and a small amount of food to help the new plant grow, all enclosed within a protective coating.

With luck, one of these spores will land in an opportune place and grow into a different plant that is the second phase of the fern lifecycle: a gametophyte. Small and inconspicuous, many people are completely unfamiliar with gametophytes. Their job is to produce eggs and sperm.

When an egg is successfully fertilized, it grows into an embryo. This embryo grows up and out of the gametophyte into a new sporophyte—and the cycle begins again.

Studying ferns today

Vasco currently studies the Ferns of Colombia; Colombia is both her birthplace and the home to the greatest diversity of ferns in the Americas with more than 1500 species. Most of the ferns are found in mountain forests, but these ecosystems are at extreme risk of deforestation.

“Only ten percent of the mountain forest is left,” says Vasco. “We are on a race against deforestation. We fear that many ferns species will go extinct before we can describe them and show them to the world.”

Dinosaurs and the big picture of conservation

When people ask Vasco why she and her colleagues put so much effort into finding and protecting ferns that grow on remote mountains in a country two thousand miles away, Vasco points back to where this story started: with dinosaurs.

“Dinosaurs went extinct because a meteorite that fell to earth about 66 million years ago,” says Vasco. “That might seem like an isolated event—a meteorite striking Mexico. Yet this event changed the entire world.”

In fact, 75 percent of all species on earth were wiped out by the meteorite, including all non-avian dinosaurs and vast numbers of fish, insects, microbes and plants. This event wasn’t isolated at all, because the earth is actually a single ecosystem.

“It shows that everything is connected ,” says Vasco. “When something is not conserved in one place, the entire world suffers.”

When you visit the dinosaurs around the Garden this spring, close your eyes and try to imagine these remarkable creatures surrounded by towering ferns and enormous lycophytes. And remember: we are all connected, sometimes in ways we barely understand.