This piece is authored by Mare Nazaire Ph.D, Administrative Curator, Herbarium, California Botanic Garden (RSA) as part of the Botany Stories series highlighting unheard stories of botanists at BRIT and beyond.

China: Collecting the Asian Species of Mertensia (Boraginaceae)

To answer questions about the biogeography of plants, you often must go to where the plants are. My dissertation research focused on the phylogenetic systematics and biogeographic patterns and origins of Mertensia (Bluebells), a genus in the family Boraginaceae. Mertensia is a genus of primarily montane, alpine, and northern latitude habitats in North America and Asia, and I was interested to understand and explain the current patterns of distribution and determine its origins. To understand relationships between North America and Asia requires having specimens from Asia, for which our North American herbaria are quite depauperate. I was fortunate to receive the East Asian and Pacific Summer Institute (EAPSI) fellowship to China in 2010, which permitted me to travel to, examine, and sample specimens in herbaria there and to conduct fieldwork to collect Mertensia in the northern regions of China, where Mertensia reaches the southern extent of its distribution.

EAPSI, funded by the National Science Foundation, provides U.S. graduate students in science, engineering, and education first hand research experience in Australia, China, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Singapore, or Taiwan. The program also provides an introduction to science, science policy, and infrastructure as well as an orientation to the society, culture, and language of a participating country. Students in the program are immersed in the culture of participating countries for two months. This is a wonderful experience to learn about the culture of another country and make important connections that often turn into future research collaborations. Unfortunately, this program is currently suspended.

Beijing: PE Herbarium

My fellowship began in Beijing, a big, energetic city with endless options for excellent food (food, by the way is a top priority for botanists!), and to learn the fascinating history and culture of the city through its historic sites. Much of my time in the beginning of my fellowship was spent in the Herbarium at the Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences [PE], where my host, Dr. Xiao Quan Wang, is located. I was particularly interested in working with Dr. Wang, considering that his research centers on biogeographic questions between Asia and North America with the genus Pinus (Pinaceae). He had an amazing cadre of graduate students that welcomed me, showed me around, and brought me to the best local restaurants and sites!

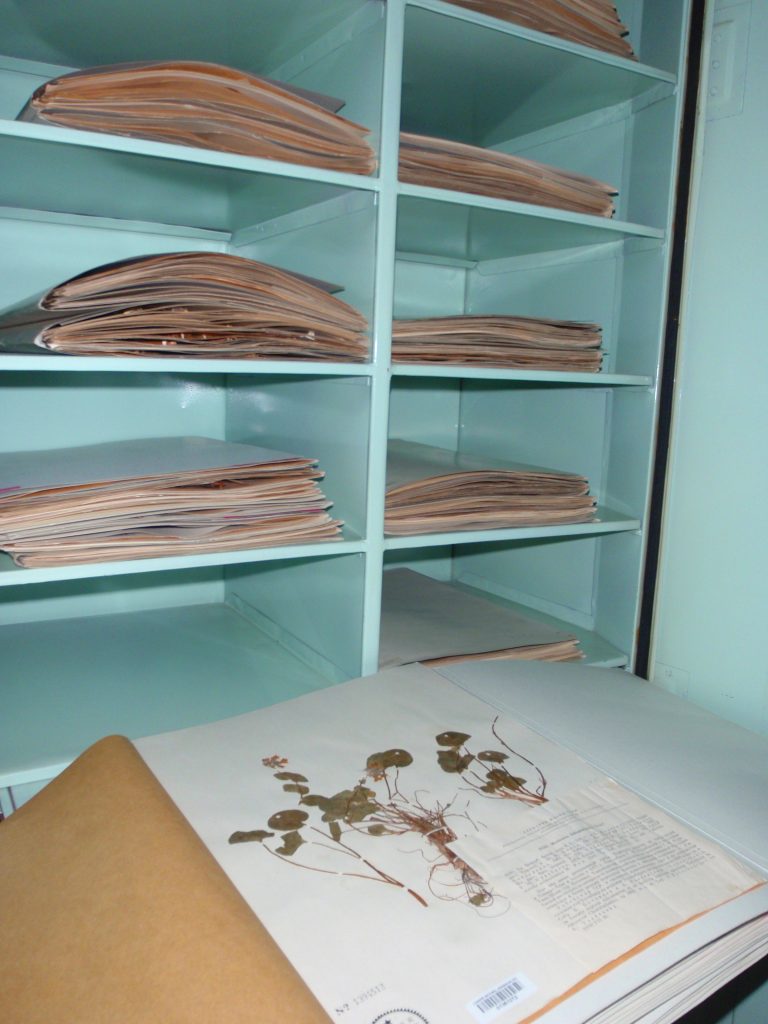

A confession: I love traveling to and visiting other herbaria! I learn so much by visiting other collections, and I love learning about the little details and nuances that make that collection unique. PE, a rather dark herbarium, the air thickly drenched in para-dichlorobenzene (so much so that your throat, nose and eyes burn after having spent a day there), has an amazing collection of vascular plants. While there I spent most of my time primarily in the wing where Boraginaceae is housed, examining specimens of Mertensia. In addition to an excellent representation of Asian Mertensia, I was quite surprised to discover the sheer number of North American collections there, and even some collections from California Botanic Garden Herbarium (which at that time it was inconceivable that I would later become the Administrative Curator of that collection!). One major challenge for me was that I was not well versed in translating the Chinese language, so I relied heavily (and thankfully) on my graduate student colleagues for helping me with the translations of the collection label information.

Dongling Mountain: Mertensia davurica

Several key collecting trips were planned during my fellowship, one being to Dongling Mountain in the Ling Mountain Natural Reserve in Hebei Province south of Beijing. Mertensia davurica reaches the southern extent of its range in the highest mountains there. Accompanying me on this trip were two of Dr. Wang’s graduate students, Yu Zhi Cun and Yan Yan Guo. Yu Zhi was also working on his dissertation, examining the phylogeography of three closely related species of Tsuga (Hemlock) and was interested in making collections of any populations of Tsuga that we encountered. For all of the collecting trips in China, the journey to the site was always a story of its own. Our terrifying drive to the Reserve involved very narrow roads and passing cars and trucks on blind curves. This was followed by traversing partway up the mountain by horse. The last leg of our journey into the alpine zone was made on foot where we scoured steep slopes looking for our plant. On a west-facing slope in an alpine meadow I spotted our plant – the long, pale blue corollas hidden among the sedges, potentilla, geranium, and poppies. One unusual and defining character for Mertensia davurica is its extremely long corolla tube – the longest of any Mertensia. They curve in comical ways, not a character that I have seen in other Mertensias. We collected several specimens, and also leaf samples in silica gel – to dry the leaves quickly for better preservation of DNA, which I would extract later on when I returned home.

Guan Di Mountain: Mertensia sibirica

Guan Di Mountain is located in the Pang Quan Gou National Natural Preserve in Shanxi Province. With Yu Zhi Cun and another graduate student, Zhen Zhen Hao, we traveled first by train to the province, then by car with hired driver to the village at the base of the Preserve. In the village we inquired with the locals about the plant we were seeking and if they had ever seen it, and if so, its location. Yu Zhi arranged for one of the locals to drive us to the area where we might find it. We climbed into a bright blue three-wheeled vehicle, traveling up a rough, rocky, steep, gravel road until the vehicle could not go any further. We hiked the rest of the way into the clouds, the vegetation dripping with cloud mist and giving the summit a mysterious feel. Just as we turned a curve in the road, we spotted our plant: below the summit on a south-facing slope we found a very localized population of Mertensia sibirica.

Maybe other botanists feel this way when they are out searching for a specific plant, but with Mertensia I would frequently have this hunch that we were about to find our plant – the habitat seemed right, the associated plant species seemed right, the soils seemed right. I can’t remember exactly, but I might have squealed with sheer delight when we found Mertensia sibirica. It looks very similar morphologically to several species that occur in North America. We collected several specimens and searched along the mountain for other individuals, but this was the only patch where we found it. We returned to the village, the local people wanted to know if we were successful in finding our plant. We shared our stories – our vehicle breakdown and our discoveries – and I showed them the specimens we collected. They were delighted that our trip was met with success!

Xinjiang Province

Probably the most thrilling collection trip during my fellowship – despite the disappointment of not returning with any collections of Mertensia – was traveling to the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. Accompanied by Dr. Wang’s graduate student Ming Ming Wang, we traveled by plane across the country to the northwestern province of China. In Ürümqi, I met my second host, Dr. Dun Yun Tan, a professor at Xinjiang Agricultural University who studies plants of the cold deserts in northwestern China. Dr. Tan’s graduate student Ming Ming and Zhai Wei would assist me on several collection trips in this region. Both Dr. Wang and Dr. Tan had set up my permit to travel there.

Several species of Mertensia occur in the northern and western edges of the country, in the Altai Mountains bordering Mongolia and in the mountains bordering Kazakhstan-Kyrgystan: Mertensia tarbagatiaca, M. popovii, M. meyeriana, and M. dshagastanica. We had anticipated being able to locate populations of several of these species. Our first trip was to the Jimunai region bordering Kazakhstan. With each town or city in China a foreigner must register with the local police. Because I was not fluent in, nor could read Chinese, I was unaware that Ming Ming had brought me to a town that was not included in my permit. While they allowed us to stay a couple of nights in the town so that Ming Ming could collect in the Saur Mountains, an eastern extension of the Tarbagatai Mountains, I was not permitted to go, especially since they did not permit foreigners close to the Kazakhstan border.

This is pretty much how my trip in Xinjiang went – arriving to towns that were not on my permit and being asked (or told in some instances) to leave. This was coupled with many unsuccessful collecting excursions of not finding Mertensia. One trip to a mountainous area in the Yining region was thwarted by the road being washed out. With Zhai Wei we traveled to Wusun Mountain, and while we never did find Mertensia there, the landscape and hillsides of wildflowers were well worth the trip. Towards the end of the Xinjiang trip we met up with Dr. Tan and colleagues for some general collecting in the region.

While not successful with finding Mertensia, I was able to sample leaf material for DNA extractions from specimens housed in the herbaria at the Xinjiang Agricultural University [XJA] and the Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences [XJBI].

One final note to add is the important and lasting connections I made during my trip to China and expanding my botany community. My gracious hosts and their students greatly helped me to further my research and understanding of the biogeographic relationships in Mertensia. Indeed, without their help I wouldn’t have been able to answer any of those questions I had about the biogeography of Mertensia. I was eager to return the gesture. With students I helped with preparing their manuscripts for publication in English. It was extremely satisfying to help them in this way, and my collaborations with them have continued well beyond this fellowship.

Mare Nazaire Ph.D, is a research botanist and Administrative Curator, Herbarium, at California Botanic Garden (RSA).