Article originally published in The Leaflet (March 2014) by Brian Witte, PhD, BRIT Research Associate

Identifying a nameless specimen brings tremendous satisfaction. Naming seems simple. It’s just two words, after all. And yet, a world of stories is implicit in every name. Some of that story is explicit in the labels we affix to specimens: the when, where, and who of the moment it was collected. Much of the story, though, is implicit in the name of the plant. The two words of a scientific name, genus and species, refer to the place of the plant in 4 billion years of evolutionary history. Every species within a genus is, in theory, more closely related than to any species in any other genus. Likewise, all the genera grouped within a family are more closely related than to any genus in a different family, and so on up through order, class, phylum, kingdom, and domain.

A name, then, is a way of saying “I see this plant, with all of its unique association of leaf shape, seed pods, flower structure, branching pattern, and there is only one name that fits that pattern.”

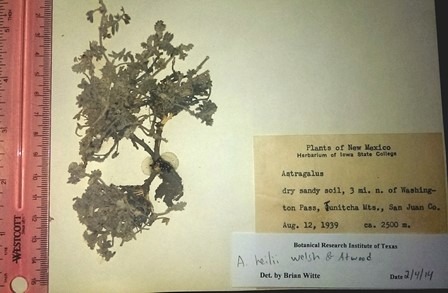

The satisfaction of naming a specimen is all the more profound when it has lain unnamed for some time. My Astragalus project, for example, focuses on specimens collected over thirty years ago. As much as I enjoy bringing resolution to that project, I sometimes find something truly remarkable. Most recently, this was collection number 3218 by Geo. J Goodman and Lois B. Payson. #3218 is a tiny tuft of gray-green herbage that was pulled from a patch of “dry sandy soil” in the Tunitcha Mountains of San Juan County, New Mexico…in 1939. For 75 years, these two tiny plants had lain unrecognized until I was able to determine their identity as Astragalus heilii.

In some ways, it is hardly surprising that these plants went so long without being known. In 1939 there was no Astragalus heilii. Or rather, the plants obviously existed, but no one had yet recognized that peculiar combination of characteristics was worthy of a name of its own. It wasn’t until 2003 that A. spheilii was defined, and as of 2014 only 8 (now 9) collections are known to exist, and all from two counties in northwestern New Mexico.

To anyone not intimately acquainted with taxonomy, this must sound painfully obscure, even trivial. Naming this one specimen, though, strikes close to the heart of why I love science and why I continue to drive 70 miles roundtrip to volunteer one day a week in the herbarium. Seeing the identity of this plant, unique among the 1.2 million specimens at BRIT, means that I am able to distinguish it from every other living thing on the planet. Finding a name for it means it can join the collection, that its atoms we prevented from returning to the atmosphere have a purpose in educating future generations of scientists. The plant itself can hardly care about a name (“A rose by any other name…” etc.), but without a name, it is simply an enigma to us…and for the past 75 years it has been just that: an enigma, albeit a small one. Now, thanks to George Goodman, Lois Payson, and me, the mystery is solved and our knowledge of the natural world is a tiny bit more rich.

You’re welcome. 🙂