What is the origin of your interest in bryophyte collections and then specifically the Bryophyte Herbarium and the Peter H. Raven Bryology Library at the Missouri Botanical Garden?

I’ve been interested in nature since childhood, but it wasn’t until taking an undergraduate plant class with Dr. Carl Chuey at Youngstown State University that I took any notice of bryophytes. I still vividly recall my first look under the microscope at a clump of moss. I was pretty much hooked after that and began collecting bryophytes to study. A summer internship at the Duke Herbarium allowed me to work on bryophyte specimens alongside Dr. Lewis Anderson. That summer I met numerous other bryologists, one of which was Dr. Bruce Allen from the Missouri Botanical Garden (MO). He told me about MO and encouraged me to apply to its graduate degree program. Later, during a visit to MO, I was astounded by the size of the collection and knew I wanted to be connected with the institution. After finishing my M.S. degree, I was fortunate to be hired as a research specialist in the bryophyte herbarium and library.

What are the strengths of the Bryophyte Herbarium and Bryology Library?

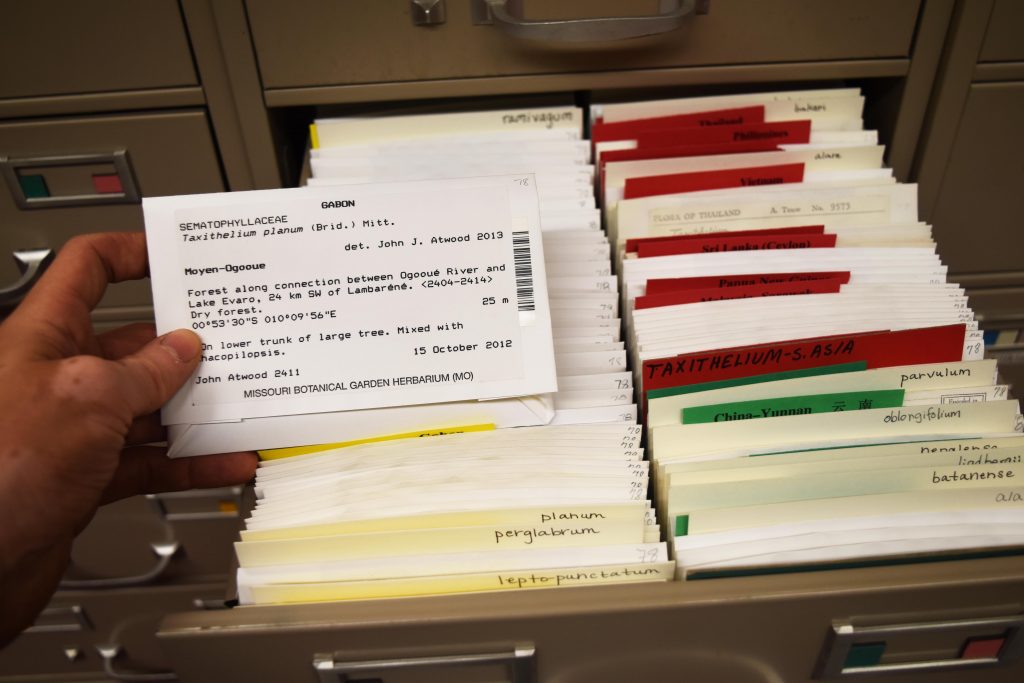

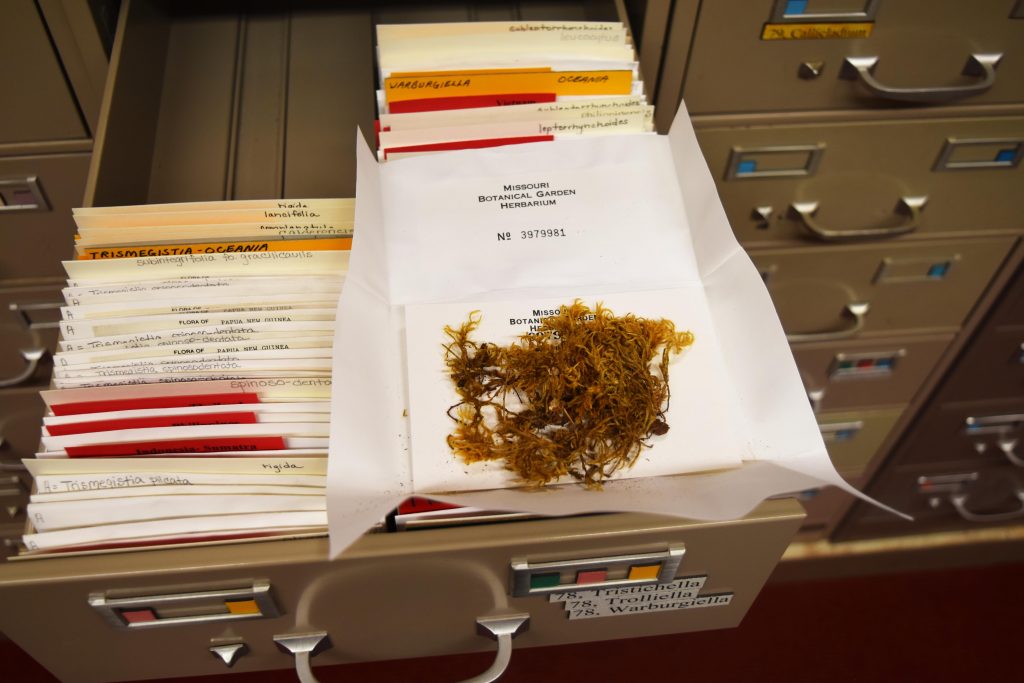

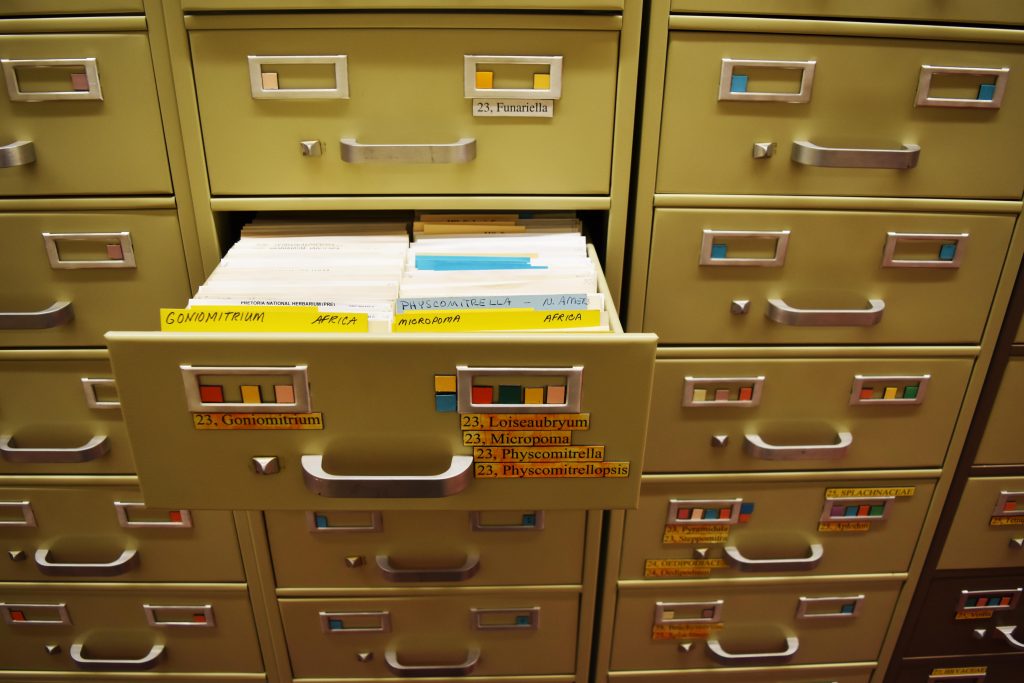

The size of the bryophyte collection, with nearly 600,000 specimens, is a strength that immediately comes to mind. Finding good, comparative material is almost never a problem. This strength can be attributed to MO’s collecting programs in numerous countries, an extensive list of specimen exchange partners, and its acquisition of several important bryophyte herbaria. A strength of equal importance is the number of relatively recent specimens in the herbarium. Many of these specimens are being utilized in molecular phylogenetic studies, making them critical reference material.

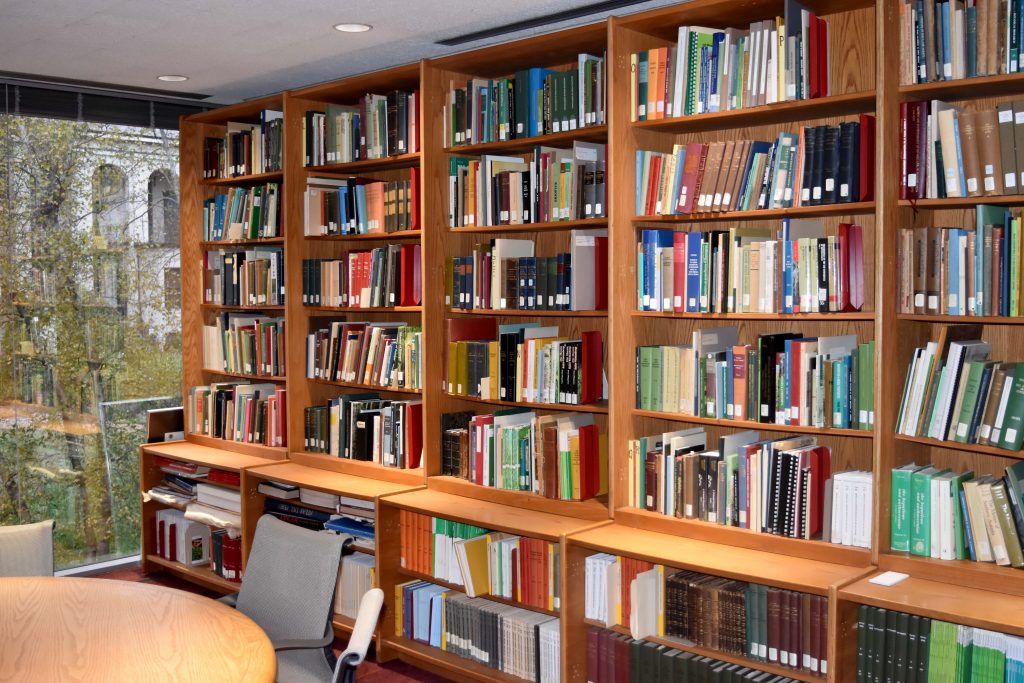

The comprehensiveness of the bryology library parallels the vastness of the herbarium. For nearly 50 years, MO has been coordinating the Recent Literature on Bryophytes project. This project compiles quarterly lists of bryological literature with the complete bibliography available in a searchable online format. A huge collection of articles, theses, technical reports and books have accumulated as a result of authors sending reprints for inclusion in the project.

What do you find most interesting about the collections? Are there any hidden gems within the collections? What is something only you know about the collections?

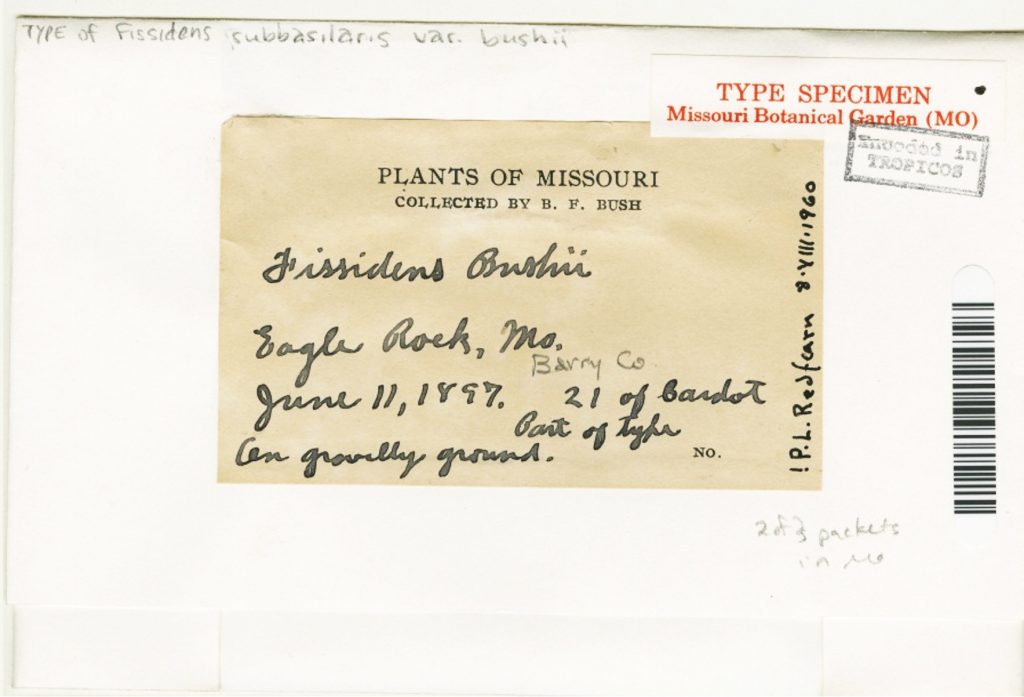

The backlog of undetermined, unprocessed specimens is immensely interesting. By opening these boxes, one can be immersed in an exotic destination’s flora. One week I might be matching labels to moss specimens from China and the next week be sorting liverwort specimens from Peru. The backlog is full of hidden gems, such as undocumented range extensions for species, species new to science, and poorly known species that have yet to be adequately studied. Working with the backlog is by no means straightforward and often requires a bit of detective work. Doing this work, however, gives me insight into the collection that few others have. For example, some specimens require considerable investigation because information gets lost or buried as specimens move between offices and staff retire. Resolving the location or collector of a specimen might involve comparing handwriting samples or looking for patterns between dates and collection numbers. Several boxes of specimens whose data would have been lost to time have since made it into the herbarium through this process.

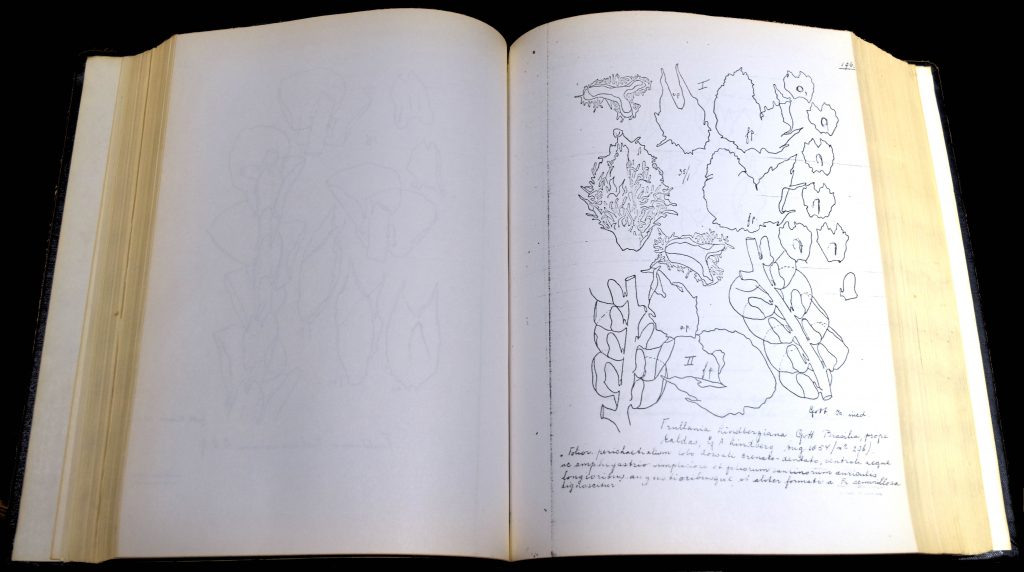

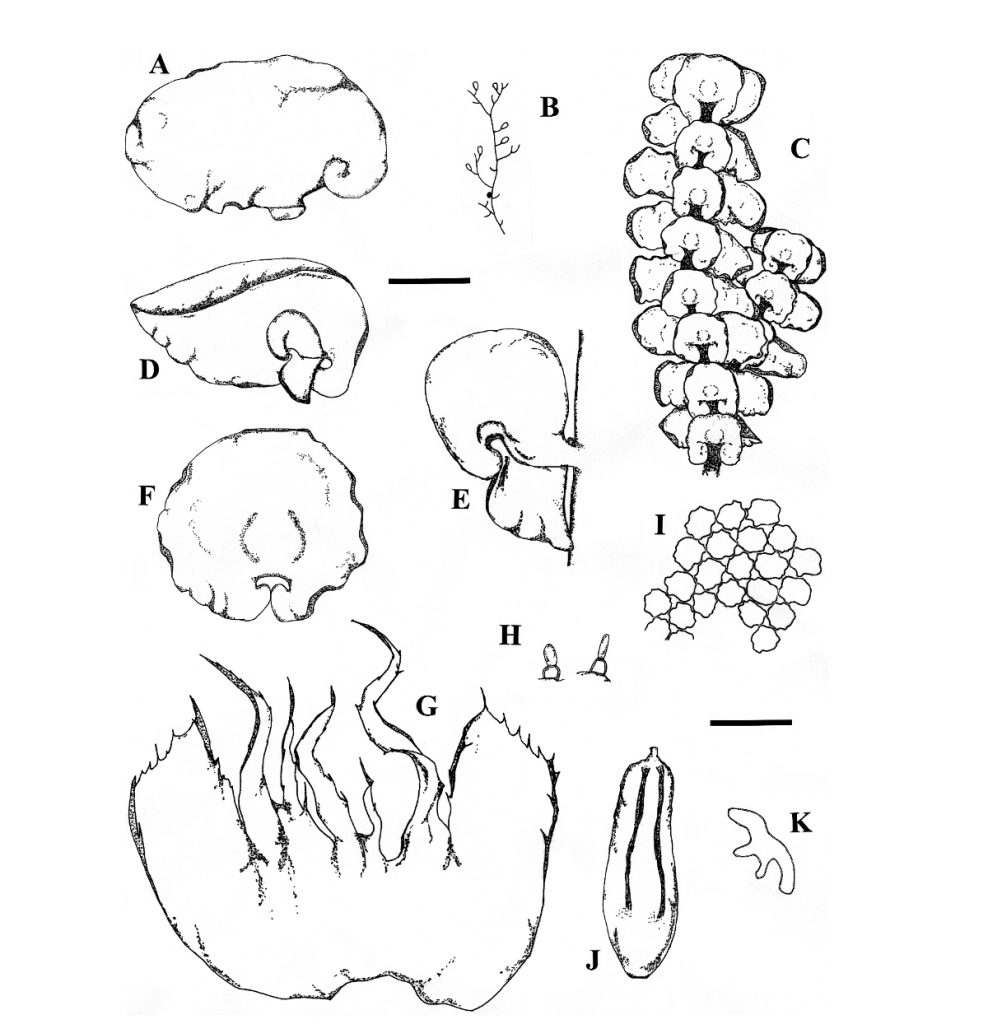

Some of the best gems in the Bryology Library are bound copies of unpublished specimen illustrations such as Frans Verdoorn’s “Icones Jubulearum”. The MO copy is one of only six in existence. Botanical illustrations can be valuable in their own right as works of art, however in this case, type specimens of numerous Frullania species are illustrated by an authority on that particular group of plants, making it a critical reference tool for taxonomic studies.

What has been the most compelling and challenging aspects of your position overseeing these two collections? What is one of the most valuable things you’ve learned through the years?

The MO bryophyte herbarium and library are some of the largest in the world, and I am often compelled to maintain a high level of organization within these collections. On the other hand, faced with numerous daily tasks that all require attention, staying focused and not getting overwhelmed can be a challenge. In addition to maintaining the collections, I am responsible for processing specimen incoming and outgoing loans, gifts and exchanges; databasing new specimens, mounting and filing; managing a pool of volunteers, and pursuing my own research projects. This challenge has taught me the importance of time management. Also, I have learned that multitasking does not make me more efficient. Rather, I have become a list maker instead. Checking off projects from a list is particularly gratifying, especially when those projects have been ongoing for days or weeks.

In what ways have the collections grown during your tenure, and what is one of the ways that it is currently growing that warrants particular attention?

I am particularly proud of growing the collection of liverwort specimens at MO. Historically, research in the bryophyte herbarium has focused primarily on mosses. Liverwort specimens, while collected and received as gifts and exchanges, were given less attention. Over the last several years, I’ve been working to improve their level of curation. Early on, this involved sorting specimens by genus and adding species and country cards to the alphabetical filing system. However, it soon became obvious that a new filing system was needed. Very little cross-referencing of synonymous names had been done, resulting in a chaotic arrangement with the same species filed under two, sometimes as many as four, different names. Liverwort specimens are now filed according to the classification in the World Checklist of Hornworts and Liverworts. Related genera and species are now filed next to each other, facilitating their comparison when trying to name an unknown specimen.

How are the two collections valuable to each other?

The relationship between the library and bryophyte herbarium is probably most evident in Tropicos, MO’s online, searchable database of plant specimens, names and references. New references are continuously added to the database, and plant names and herbarium specimen records are modified based on information in those references. As new references are entered, a fair amount of time is spent searching for MO specimens that might be cited in those publications. I am often surprised by the number of specimen duplicates that are in the herbarium but are not cited in publications as having been deposited in MO. Herbarium specimens are also regularly updated using newly published nomenclature or are annotated based on citations from the literature. This ensures that the collection keeps pace with the most recent taxonomic and floristic research in the field.

How are the collections helping to preserve the past, present, and future of biodiversity?

The study of biodiversity depends largely upon the quality of specimens and their precise and accurate label information. The accumulation of herbarium specimens from a particular area highlights diverse habitats as well as rare species and helps guide conservation priorities. For Missouri bryophytes, the MO bryophyte herbarium works closely with the Missouri Department of Conservation to establish which species are most endangered and require state-listing as species of conservation concern. Since specimens provide direct evidence of a species’ distribution at a particular time, herbarium specimens also establish baseline data, from which the loss or gain of species can be monitored. This is evident in the number of collections made of a particular species through time across many localities, but also for monitoring single localities that have undergone significant environmental degradation, as some populations will no longer exist in nature. Lastly, numerous floristic works on bryophytes are being coordinated at MO, such as the Bryophyte Flora of North America, the Moss Flora of China, and the Bryophytes of the Tropical Andes. The greater understanding of bryophytes promoted in these works reflects our best efforts to catalog global bryophyte diversity and distribution, as well as heighten public awareness of these plants.

Where do you see bryophyte herbaria/library collections in the future? How do you see them evolving with the times?

Herbaria and libraries will continue to digitize their collections and promote open-access, virtual content with more efforts to interconnect these databases and collections. For bryophyte herbaria, I think efforts should be directed particularly towards digitizing microscope slide collections. Digitized images of dried bryophyte specimens often present too many limitations to adequately depict the characters needed for species-level identification.

An evolving trend currently impacting herbaria has been a change in the age of the specimens being borrowed, and in the purpose for which these specimens are being requested. There has been a sharp increase in loan requests for use of recent herbarium specimens for phylogenetic analyses. Genetic sequences obtained from the specimens are often deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s database, GenBank. Sequences are given an accession number, but often the kind of data that herbaria use to cite specimens (e.g. collector, collection number and institution) is not adequately recorded. Keeping the connection between genetic sequences and specimen vouchers is critically important. Researchers commonly download and use molecular sequence data from GenBank without checking the specimen’s identity. This has led to incorrectly named specimens being included in phylogenetic studies. The MO herbarium is adapting to this change both in revising specimen use policies, and developing ways to store and reference the molecular data resulting from these studies.

Another trend is the increase of new and obscure online-only journals. I have concerns about whether article from these journals will be retrievable in the distant future. When possible, I obtain hardcopies of every publication for the bryology library. I believe that the library will be an important archive for these kinds of reference materials.

If you were given a free week with each collection, entirely extra time, what would you do?

In the herbarium, I would continue to organize the specimen backlog. Besides getting label data attached to the specimen packets, there are numerous mixed specimens that need curating to separate out the various species. Dividing specimens and assigning them preliminary generic or family names so that they can be sent to specialists for closer study is on my wish list.

For the library, I would digitize the original, hand-written index cards that were used to compile the moss nomenclatural catalogue, Index Muscorum. The cards have historical value since the Index is the backbone of many moss-focused projects in the Tropicos database. Interestingly, these cards include citations for published moss forms. Forms, like varieties or subspecies, are a rank below species but nevertheless examples of biodiversity. The number of described moss forms is unknown because forms have never been systematically catalogued. Form names were not included in the Index, and are still mostly lacking from the Tropicos database. With free time, I would use these cards to guide a literature review to locate names of overlooked moss forms. I’d feel really good about getting all of that done. You did say a free year for each, right?

John Atwood is a Research Specialist at the Missouri Botanical Garden Herbarium in St. Louis, Missouri.

Special thanks to Doug Holland, Director of the Peter H. Raven Library, and Andrew Colligan, Archivist. Header image by Steve Frank. Courtesy of the Peter H. Raven Library.