In the conservation community, there is often nothing more rewarding than walking through a landscape that you had a hand in saving and knowing that you did good. You saved this rare and valuable natural treasure for future generations. This is conservation at its finest and what most in the conservation community strive for. But there’s so much more that goes into the process, and believe it or not, it’s the early steps that I find most exciting.

And what is that first step? Documentation!

I know. It doesn’t sound that exciting, but we can’t protect what we don’t know. Before we can protect a piece of land, we need to know what we stand to lose if we fail; before we can restore a degraded prairie, we have to know what we are working towards; before we can protect a rare species, we need to know first that it exists and then that it is truly in need of protection. All of these conservation actions require that we know about the plants and ecosystems that we’re trying to conserve. Without this basic knowledge, we could easily squander our limited time and resources protecting a species or a piece of land that doesn’t need our protection. Cataloging diversity enables us to prioritize our efforts and identify what is truly at risk and what is truly unique.

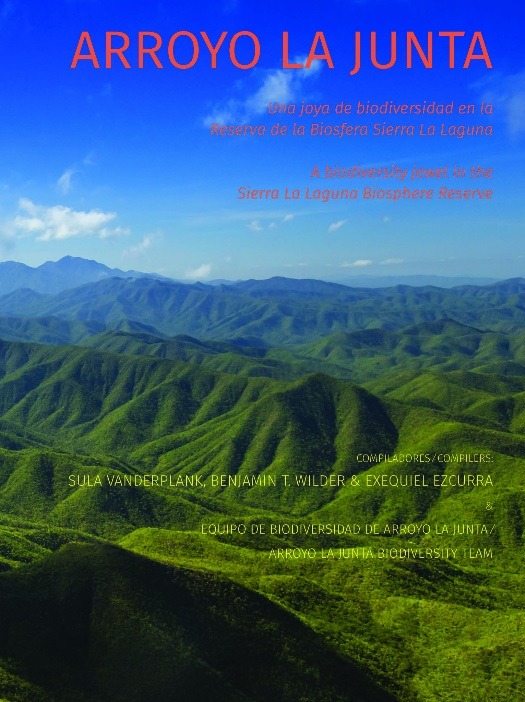

This idea of conservation through documentation has been a cornerstone of BRIT research for years. Our past projects in Peru, Jamaica, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, and even right here in Texas have actively cataloged plant diversity. BRIT Biodiversity Explorer Dr. Sula Vanderplank is currently on the front lines of this work. Her biodiversity surveys in Baja California are working to catalog the total biodiversity of areas threatened by development or mining. Without these surveys there would be no evidence of the impact these developments would have on natural ecosystems and no sense of what was at stake. I was amazed when I saw that 29 species protected under Mexican law were in the proposed impact area for a gold mine inside the Sierra de la Laguna Biosphere Reserve. Sula’s work has brought the well-being of these treasures to the forefront. We now know what we stand to lose.

The protection of any plant, animal, or ecosystem is contingent upon the ability to recognize that it exists in the first place. Many of our rare plants and ecosystems are still unknown to us. BRIT Vice President of Research, Dr. Peter Fritsch, recently described a new species of wintergreen (Gaultheria marronina) from the mountains of Sichuan, China. This new species is only known from two populations worldwide and is classified as endangered. Documenting the very existence of this species puts it on the radar for conservation. Without a name, this plant would forever live in obscurity and quite possibly be lost to extinction.

This same concept applies to ecosystems as well species. A plant community without a name can easily be overlooked. BRIT Biodiversity Explorer (and my mentor), Dr. Dwayne Estes, is working on the Pennyroyal Plain prairies, a little known prairie system in Tennessee and Kentucky. This system once spanned more than 200 miles, but today has only a few small remnants. The drastic contrast between this open grassland system and the surrounding forest landscape means that by its very nature, it harbors a unique set of plant species. With the loss of this system, many of the Pennyroyal Plain species, such as the rare Rudbeckia subtomentosa (sweet coneflower), are at risk. We will never know how many species were lost before scientists began documenting the diversity here. Without thorough documentation, this system could’ve gone unnoticed, and its remaining treasures lost forever.

Once we know that a plant or community exists, we have to determine if it’s truly in need of protection. Over the past six years I’ve worked to understand the distributions of rare and endemic species in Texas. We’ve shown that species which were previously thought to be rare, or not known to occur in our region, are actually common in certain habitats. We now know what truly needs to be done to conserve rare species like Dalea reverchonii (Comanche Peak Prairie Clover), Gratiola quartermaniae (Quarterman’s hedge hyssop), and Isoetes butleri (Butler’s quillwort). Currently, I’m documenting the distribution of four rare species in north Texas. This summer I began working on one of these, Pediomelum reverchonii (Reverchon’s scurfpea). When I first started the project there were only 10 known populations from the state of Texas (and only 15 outside of Texas, all from Oklahoma). During the course of the last month we’ve documented nine previously unknown populations, and we have only just begun. Finding and documenting these populations is the first step. Once we know where it grows, how abundant it is, and what habitat it prefers, we can begin to make informed decisions about the future of this rare species and work strategically towards its conservation. It’s an exciting process, and it all starts with documentation!