In the Collection Lens series, BRIT Librarian, Brandy Watts, highlights collection managers from around the world across botanical libraries and herbaria as collections move into the future in an effort to drawn attention to the value of botanical collections and facilitate better understanding and appreciation of their importance and crucial role in preserving and promoting biodiversity data and the vast history of botany.

What is the origin of your interest in herbaria and the Huntington Herbarium specifically?

Herbaria hadn’t really been on my radar until the early 2000’s. I remember talking to a committee member for my Master’s thesis and he asked where my vouchers [specimens] were from all my collection sites, since I undertook a developmental project that sampled many plants. I only had photographs and GPS coordinates, without any physical specimens. That was the moment when I realized how important a physical specimen was that linked a plant to a place and a time.

In 2005, I began working with the Huntington Herbarium (HNT), as part of my broader duties as the newly appointed Plant Conservation Specialist at the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. My knowledge was quite limited at the time and I really submerged myself in the local herbarium community, which helped me get up to speed with basic herbarium best practices.

What are the strengths of the Herbarium’s collection?

HNT has really carved out a special niche in the herbarium world. Our biggest strength is probably the high number of unique taxa that are represented in the cultivated vouchers from our living plant collection. Another strength is our historical focus on cacti and succulents: 24% of our collection is currently made up of succulent plant taxa and even more staggering is that 75% of our type specimens are from succulent taxa. We have important holdings in the Cactaceae and Crassulaceae in particular.

What do you find most interesting about the Herbarium? Is there a hidden gem within the collection? What is something only you know about the collection?

I find it interesting that our herbarium acts as a continuum for our Living Collections, so that vouchers are available for long term study. Roughly half of our collection is represented by cultivated material. Although I have not pulled a number that supports this, my guess is that many of these cultivated specimens have been long lost in cultivation.

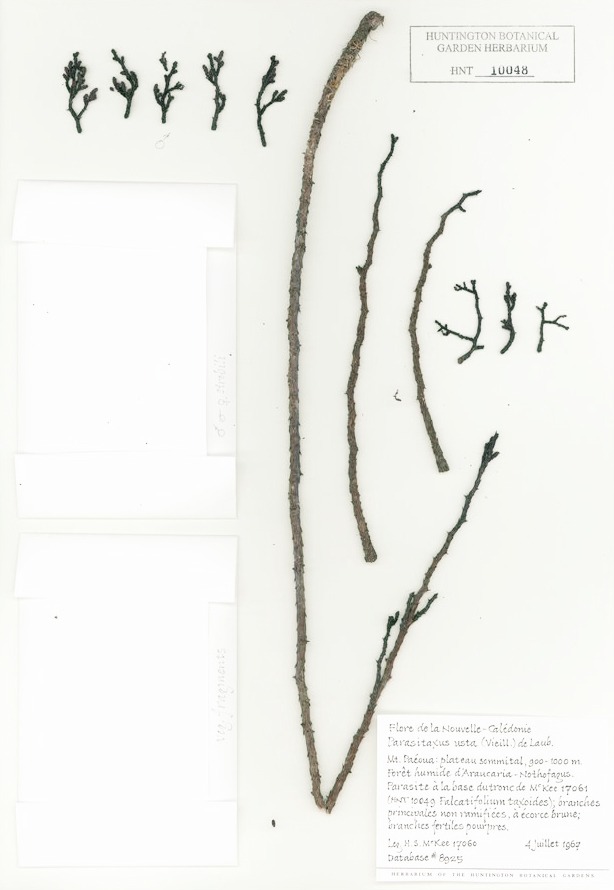

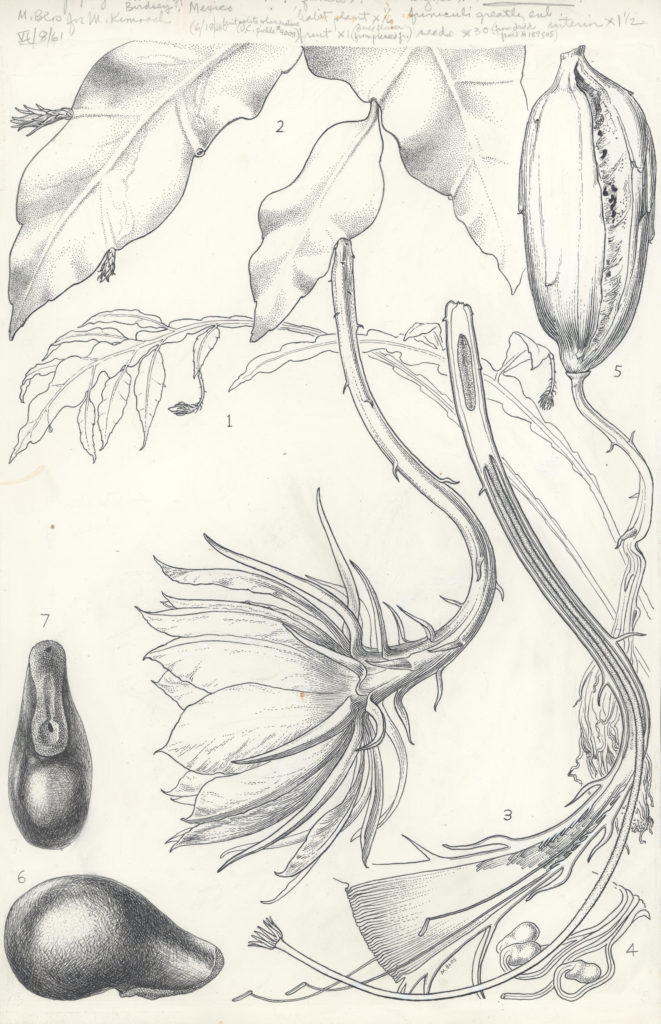

As far as hidden gems, I love to show visitors our sheets of Parasitaxus ustus (Podocarpaceae). It is an understory parasitic shrub from New Caledonia that lacks roots. Another favorite of mine is our holotype specimen of Conophytum bachelorum (Aizoaceae), which literally looks like a shriveled disk (or gem), the size of a raisin. It is critically endangered in its habitat and after the humor wears off, there is a larger story to tell. We also house a fully dried voucher of the entire spathe and spadix of Amorphophallus titanum (the storage box is over 4 feet long).

Regarding something that only I know about the collection, there are a handful of personal communications that I may not have shared with anyone else. Such as the reason why Dr. David de Laubenfels decided to donate his entire research collections of Southern Hemisphere conifers to our herbarium, when there were many other larger herbaria that would have relished at the opportunity to receive that collection. David reminded me that he grew up down the street from The Huntington, had fond memories of this museum as a child, and that it was important to him for his life’s research collection to be stored near where he grew up.

What are the most compelling and challenging aspects of your job? What is one of the most valuable things you’ve learned through the years?

The most compelling aspect of my job is the lifelong learning that accompanies the role of curating our collection. Our living collection houses the 2nd largest collection of botanical taxa of anywhere in the world and our herbarium has given me the opportunity of viewing important parts of that collection through the lens of preserved specimens. The herbarium has been both my classroom and quiet place in this regard. Other than space limitations, the most challenging part of my job is that I am limited by the amount of time that I can devote to curating the herbarium collection, despite it being the one part of my job that I really enjoy.

One of the most valuable things that I have learned is to share knowledge freely. For years, our herbarium had a retired botany professor who volunteered over 20 hours every week for about a decade. His name was Dr. Paul Meyers. He was instrumental in passing along practical information to me and I have made a point to pass on this information to any staff member or intern that spends time with our collection.

In what ways has the collection grown during your tenure and what is one of the ways that it is currently growing that warrants particular attention?

In 2005, we had 7,666 accessioned specimens at HNT and today we have over 12,900 specimens, not counting donated collections that we keep separate, such as PASA [Pasadena City College]. Considering that I am the only dedicated staff member to the herbarium, along with some longstanding help from several Curators and volunteers, I think we are on the right track. In the last decade, we have seen a real emphasis on field work centered in semi-arid and temperate regions of the United States, largely due to the good work of a dedicated Curator of Woody Plants.

How is the Herbarium’s Botany Library valuable to the Herbarium’s collection?

The botanical library is not technically part of the Herbarium, but it is an important reference collection that many of our Curators use regularly. I cannot tell you how many times I have gone upstairs to our library to retrieve the original publication for a given taxon, only to find out that we have a voucher of the type of collection housed in our herbarium. Despite not being recognized by the Shenzhen Code, these “clonotypes” are very important to our collection.

Both the Library and our Herbarium can be viewed as ancillary collections that complement and support our Living Collections. In the 1960’s, we began a series of collaborative expeditions as part of a growing field research program. As seeds were collected for our Living Collections, vouchers were made for in-country herbaria, with HNT getting duplicates. All field notes and maps have been stored in our library collection and the photos of the plants in habitat have been archived as well. In this way, all of these resources connect with each other. Our library also has a rare book collection, as well as a collection of both nursery catalogs and index semina.

Some of the big milestones during my tenure have been the adoption of periodic cold storage as a method of pest control (2006), the integration of our herbarium database into a larger relational database (2008), the digitization of our type specimen collection through the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation grant (2011), housing reference vouchers for the Global Genome Initiative Project (2019) and having all our specimen data from the Americas uploaded to SEINET (2020).

How is the Herbarium helping to preserve the past, present, and future of biodiversity?

Many of our largest Core Living Collections are CITES groups, such as cycads, cacti, and orchids. Over the years, we have prioritized making vouchers for plant taxa that are threatened in their natural habitat. Often, we discover that The Huntington is growing the only known clone of certain taxon in cultivation—a unique taxon. As mentioned earlier, one of the focal points of our collection has been an emphasis on succulent plants. As international demand for these plants has increased, wild populations for many succulent plant taxa have been threatened through over-collecting, in tandem with growing habitat loss. So, I believe our herbarium will continue to play an important baseline role in documenting the biodiversity of these niche groups, adding technology in a layered approach. For instance, one of the current projects for the Herbarium is to create a synoptic reference collection for all the past plant introductions through the International Succulent Introductions Program, a plant distribution program that was conceived in 1958 and housed at The Huntington since 1989. We are beginning to tie these vouchers to dried tissue banks for genomic sequencing (GGI Project) and in the future I can see them being tied to living tissue banks for germplasm storage and propagation.

Where do you see herbaria in the future? How do you see them evolving with the times?

I see herbaria as being more accessible to broader audience in the future. As herbaria become better digitized and plant character information is more readily available, including genomic data, I believe that this information will be utilized by people and disciplines that have not traditionally used herbaria. In the last year alone, we have seen a uptick in the amount of resident artists who have wanted to utilize our collection for interpretation, particularly from a cultural point of view.

If you were given a free week with the collection, entirely extra time, what would you do?

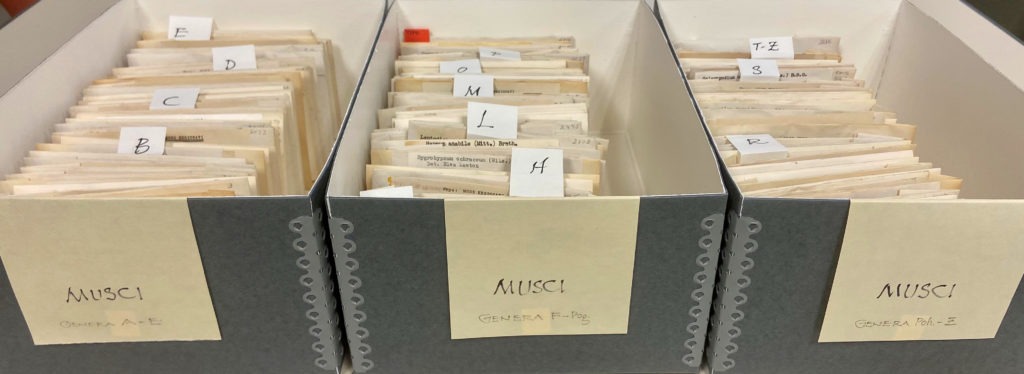

I will confess right now that I have a gift of bryophytes that have been waiting to get accessioned for over a decade and I think I could get them all accessioned in a week’s time. That being said, I would probably choose a data entry project in some capacity. We have really come a long way with digitizing our collection over the last decade, but there are many projects that always seem to be on the back burner. For instance, we have had dozens of herbarium volunteers (and even staff) through the years that have helped build our collection, but they have not been formally tracked, their names just appear sometimes as specimen collectors. It has taken me years to remember who these people are and know what projects they worked on. Perhaps I would do this and bryophyte project, just so I could sleep at night.

Sean Lahmeyer is a the Plant Collections and Conservation Manager at the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California.