This article originally appeared in BRIT’s former newsletter publication, Iridos, Issue 16(1) 2005.

“Wow!” is the most frequent comment from visitors viewing the two oldest plant specimens in the BRIT Herbarium. Both specimens were collected in Mexico in 1791 by Dr. Thaddaeus Peregrinus Xaverius Haenke (1761-1817), a widely-respected Czech botanist, world explorer, and editor of the eighth edition of Linnaeus’s Species Plantarum (1791).

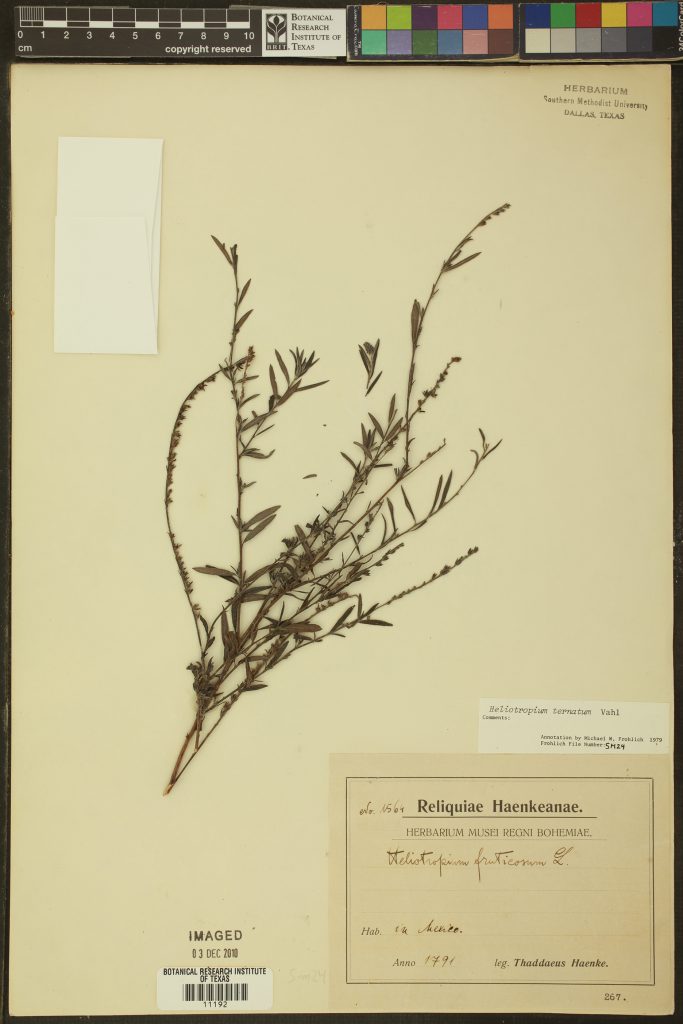

BRIT’s oldest specimen, designated by Haenke as number 1564 in his collection, is a heliotrope (Heliotropium ternatum) belonging to the Boraginaceae, or Forget-me-not family. The second oldest specimen, collection number 1666, was uncovered by Judy MacKenzie, a [former] herbarium technician who […] made it her mission to sort and file specimens BRIT has obtained from orphaned herbaria, making them accessible to researchers. The newly found specimen, in remarkably good condition, was received from the Houston Public Museum in 2001. The plant was identified by Haenke as Karwinskia umbellata, a member of the Rhamnaceae, or Buckthorn, family.

Both Haenke specimens arrived at BRIT in a roundabout manner. Haenke and French botanist Luis Née (1734-1807) were invited by King Carlos IV of Spain to join Alejandro Malaspina’s expedition in 1789 to explore natural and economic resources around the world. Arriving at the harbor a few hours late, 28 year-old Haenke learned that the expedition had already set sail. Trying to catch the expedition by sea, he barely survived a shipwreck but managed to save a few personal items and his royal letter of appointment. After arriving in South America, Haenke traveled overland to Santiago, Chile, finally joining the expedition. During the voyage, he explored and collected specimens throughout South and Central America, North America as far north as Vancouver, and westward to the Philippines and the Mariana Islands. On a trip to the Amazon Basin in 1801, he discovered the giant Victoria water lily (Victoria regia) at the Mamoré River.

During the expedition Haenke collected approximately 15,000 dried plant specimens; some of them were sent to Prague where they were placed in the National Museum. Toward the end of the expedition, eighty-five bundles of Haenke’s duplicates arrived in Spain with Malaspina but were never incorporated into any extant herbaria. Some of Haenke’s duplicates eventually ended up in herbaria in Europe and the United States. Haenke settled in Cochabamba, Bolivia, where he started a botanical garden, published his manuscripts, and worked his own silver mine until his death in 1817 from mistakenly taking poison. After his death, his notebooks and other botanically-related paraphernalia were sent to The Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid.

In the 1960s, the Lund Botanical Museum in Sweden conducted a large-scale plant exchange program with many other herbaria. It is believed that the two oldest specimens that now reside at BRIT are the result of duplicate collections of Haenke’s that were acquired through this exchange program. Is it possible the specimens that went to Spain with Malaspina ended up in Sweden? BRIT staff are eager to learn more about Haenke’s specimens and to discover more “specimens with a mysterious past” in the BRIT Herbarium.

This post is part of our “Cabinet Curiosities” series that explores significant items from the Herbarium collection. Posts are written by staff, volunteers, and interns. Read more from the series here.