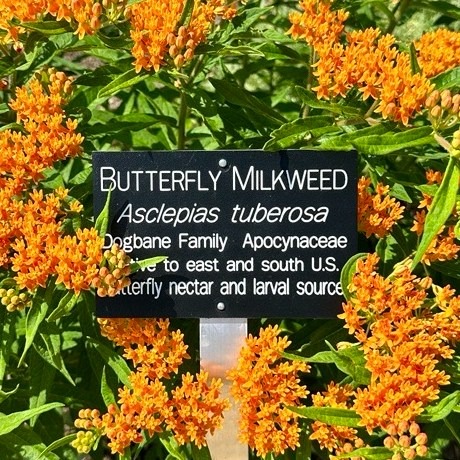

When you visit the Fort Worth Botanic Garden, you will notice signs identifying the plants. In the Japanese Garden, for example, you will see signs that read “Japanese maple” and on the next line “Acer palmatum.” Many people know that the part of the name in italics is the formal name of the plant, written in Latin. Some people might even know that Acer palmatum is the genus and species of the tree more commonly known as Japanese maple.

But why? What is the purpose of giving plants names in a dead language?

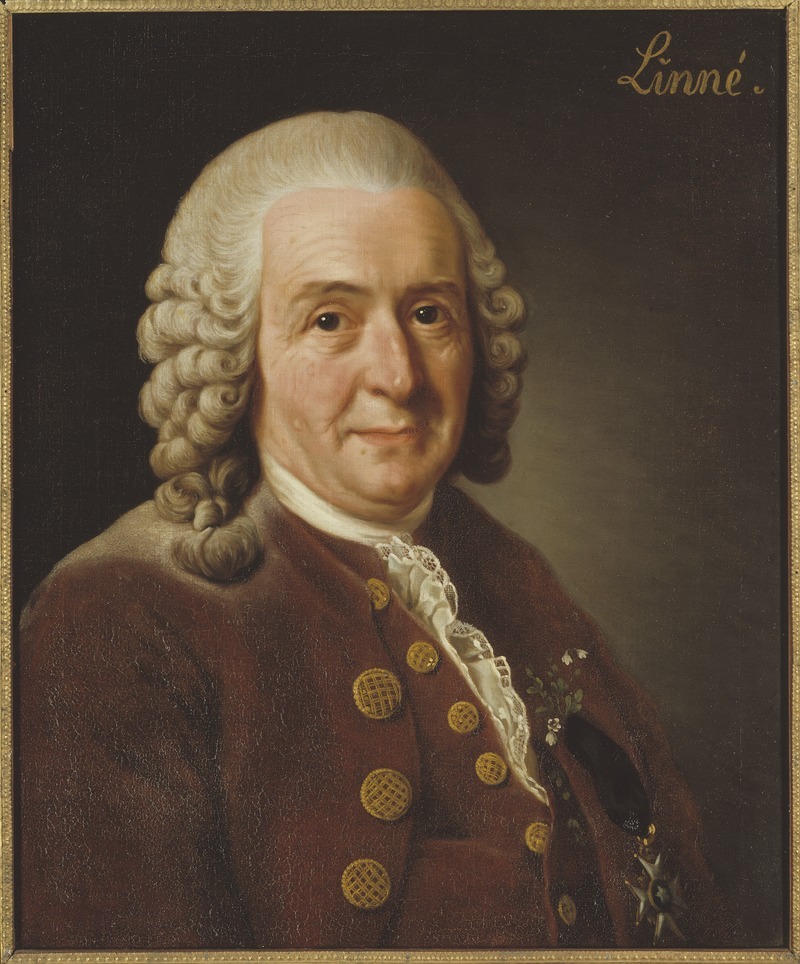

To answer that question we need to go back to a particular place and time–Sweden in the 1740s. That’s when a young doctor and botanist named Carl Linnaeus decided all of the existing systems for classifying and and naming plants were insufficient.

What’s in a name?

Greek philosopher Aristotle gets credit for developing the first known classification system for plants and animals in his Historia Animalium, written sometime in the 4th century BC. His system remained in use for almost two thousand years and was expanded by various medieval and early modern philosophers, but it was based more on abstract categorizations than actual study of nature.

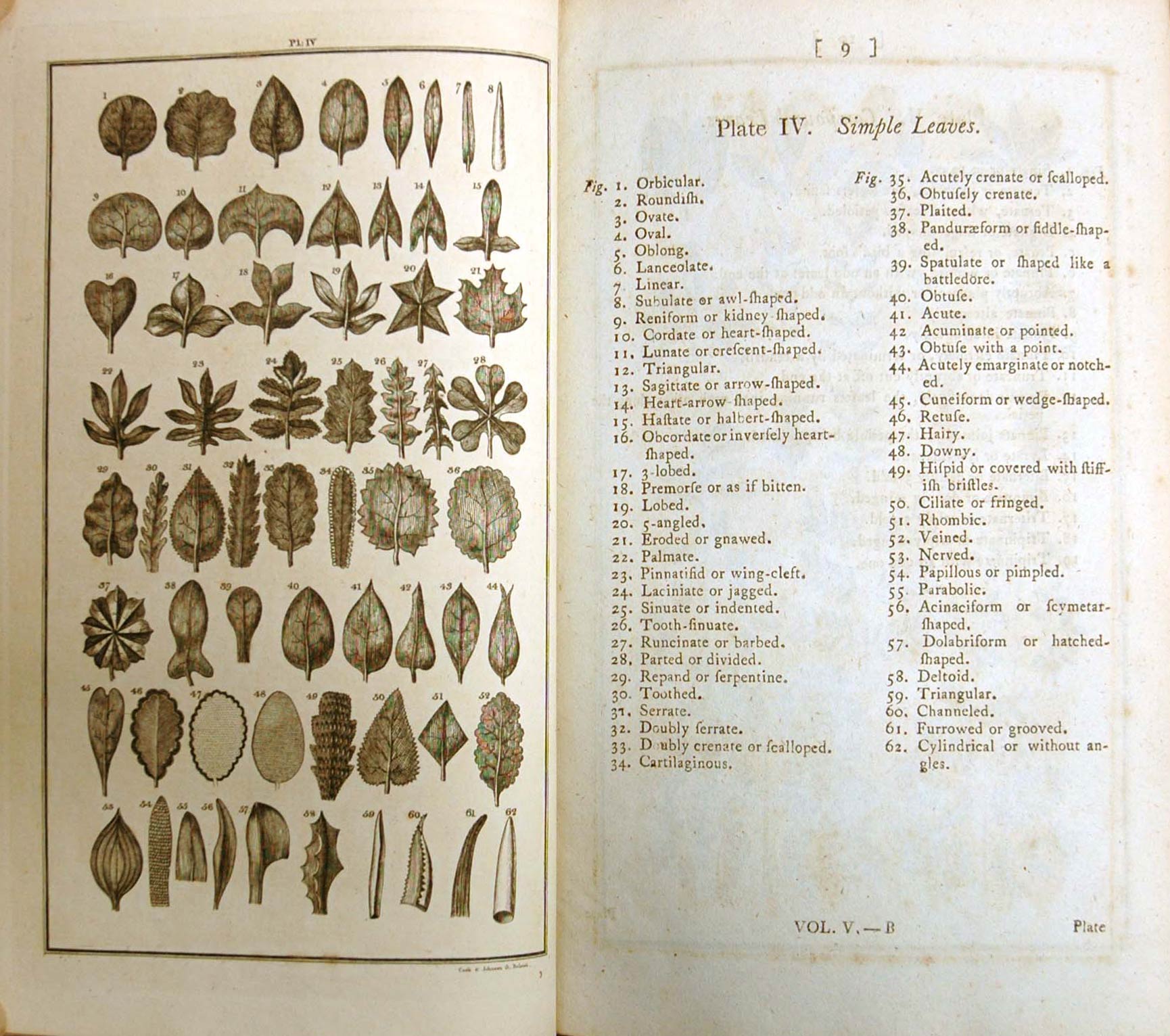

In the 17th century, natural historians began to propose new, observation-based systems for identifying and distinguishing between individual plants and animals. The most widely used approach both named the species and described it. This led to long and unwieldy name such as Plantago foliis ovato-lanceolatus pubescentibus, spica cylindrica, scapo tereti (“plantain with pubescent ovate-lanceolate leaves, a cylindric spike and a terete scape”) for what is commonly known as hoary plantain.

One of the scholars who disliked these cumbersome names was Carl Linneaus (1707-1778). The son of a minister from southern Sweden, Linnaeas was a poor student who often skipped class; he narrowly escaped life as a shoe-maker when a teacher realized that, on Linnaeus’ absences, he was prowling the countryside looking for rare plants. The teacher introduced him to botany, and Linnaeus promptly became a model student. He attended university in Sweden, qualified as a physician and obtained his doctorate in the Dutch Republic. In 1741, he joined Uppsala University, where he taught botany and natural history and ran their botanical garden.

In an attempt to replace the complicated naming system with something more workable, Linnaeas presented a system of binomial nomenclature, aka the two-name system, in his book Systema Naturae in 1736. (The BRIT Library Rare Book Room holds a copy of an 1806 English translation of Systema Naturae.) Each species is identified by its genus and species, so a blue jay is Cyanocitta cristata, a bluebonnet is Lupinus texensis, and a portobello mushroom is Agaricus bisporus.

But why the Latin? Latin was the language of international science in the 1700s. Linnaeas wrote his books in Latin, as did all scientists of the period. It had real advantages. All highly educated people in Europe studied Latin beginning in childhood, and texts written in Latin could be read by scholars from any country. It was unthinkable for Linnaeas to write in his native Swedish. Few people outside of the country could have read it, and, worse, Linnaeas wouldn’t have been taken seriously by the scientific community.

Domains, Kingdoms, and Phyla, Oh My!

The binomial naming system was rapidly adopted across Europe. Over time, Linnaeus built on this work and developed an entire system of taxonomy for both plants and animals; “taxonomy” refers to the study of naming, defining and classifying organisms. In his 1751 book Philosophia Botanica, he introduced a system that classifies living things into increasingly narrowly defined categories based on their shared characteristics.

For example, members of the Animalia kingdom with backbones are grouped into the Chordata phylum**; all chordates that produce milk are grouped into the Mammalia class; all mammals that eat meat are grouped into the Carnivora order. Each species continues to be classified according to increasingly exclusive categories until the final level of species.

Linnaeus’s worked for years classifying plants and animals according to this system, including hundreds of specimens that collectors shipped to Sweden from all around the world. By the tenth edition of Systema Naturae, he had classified 4,400 species of animals and 7,700 species of plants. To keep track of all of this data, Linnaeas began organizing species information on cards that easily could be reorganized, sorted and compared. He essentially invented the index card.

Latin may have been the lingua franca of Linnaeas and his peers, but those days are long gone. Nevertheless, botanists were required to write Latin descriptions for all newly described plant species until 2012. This requirement was finally dropped that year by the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature, the rules that govern the naming of algae, fungi and plants worldwide.

Meanwhile, Linnaeas became an international celebrity. He was knighted, elevated to the rank of nobility in Sweden, and elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1769, despite never crossing the Atlantic. Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau said of him, “I know no greater man on earth.”

Modern Taxonomy

Over time, the Linnaean system has been updated, revised and expanded many times and in many ways. One major change was the result of the development and refinement of microscopes. This led to the introduction of new kingdoms for single-cell organisms, including Protista (those with a cell nucleus) and Monera (those without a cell nucleus.)

Botany developed its own conventions. The term “division” is commonly used in place of “phylum.” The rank of “tribe” is usually added above “genus” and below “family.” Plants are often identified by either cultivar or variety names as well as their genus and species; cultivars are plants developed by breeders, while varieties are sub-species with one more distinguishing characteristics.

A significant transformation of the Linnaean system has been the result of growing understanding of evolution and genetics. Soon after Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, scientists recognized that Linnaean classification echoed the evolutionary family tree of organisms. In general, all members of each level of classification share a common ancestor. For example, at some point in the past, a chordate began producing milk to feed its young, therefore that animal and all of its descendants are classified as mammals.

| Domain: Eukarya Kingdom: Plantae Clade: Tracheophytes Clade: Angiosperms Clade: Eudicots Order: Caryophyllales Family: Cactaceae Subfamily: Opuntioideae Tribe: Opuntieae Genus: Opuntia |

prickly pear cactus genus.

As understanding of genetics and the study of DNA advanced, some biologists began to argue that taxonomy should be based entirely on the evolutionary development and diversification of organisms, what is known as “phylogenetics.” In phylogenetic nomenclature, “clades” are introduced as needed into the taxonomy; a clade is a group of organisms that share a common ancestor. As many clades as necessary can be added to mark evolutionary steps, since nature is too messy to fit into the arbitrary ranks outlined by Linnaeas. This can make the classification of an individual species very long and detailed; the classification of the mallard duck, Anas platyrhynchos, (which is under some dispute) comprises 40 clades***.

Phylogenetic nomenclature remains controversial and is not universally accepted. However, it points to the fact that the more scientists study living things, the more complicated the situation becomes. Even the concept of “species” is more confusing that it might appear–but that will need to be the topic of a future article.

Despite all of the proposed updates and revisions, the system Linnaeas proposed more than 270 years ago remains at the heart of all modern taxonomy. Herbarium staff and volunteers digitize and organize plant specimens by their Latin names. Researchers examine the characteristics and DNA of plants found in the field to place them in the right families and tribes. And horticulturists discuss plants for the Garden using the language of Julius Caesar, sometimes using the names that Carl Linnaeas himself bestowed.

It’s not surprising that Linnaeas’ system hasn’t remained static–it is the product of a different era. Nevertheless, Linnaean historian Frans Stafleu says that the system had both immediate and lasting benefits:

Descriptions were standardised, ranks fixed, names given according to precise rules and a classification proposed which permitted rapid and efficient storage and retrieval of taxonomic information. No wonder that much of what Linnaeus proposed stood the test of time. The designation of species by binary names which have the character of code designations is only one element out of many which show the profound practicality underlying Linnaeus’s activities and publications.

*The rank of “domain” was introduced in 1990 as part of a proposal for a three-domain taxonomy. It remains controversial, with other scientists proposing instead two superdomains, two empires or five dominiums.

**It’s slightly more complicated than that. In fact, “All chordates possess, at some point during their larval or adult stages, five synapomorphies, or primary physical characteristics, that distinguish them from all the other taxa. These five synapomorphies include a notochord, dorsal hollow nerve cord, endostyle or thyroid, pharyngeal slits, and a post-anal tail.” (Got that?) Nevertheless, the vast majority of chordates are members of the subphylum Vertebrata and have a backbone.

***For the complete list, visit this page and click on the “Expand” link in the “Taxonavigation” box.