Botanists and horticulturists love a challenge. That’s why this year we’re introducing a new feature in the newsletter: What Is This Thing? It’s a chance for our readers to submit plants that they can’t identify to see if we can stump our experts—and learn something along the way.

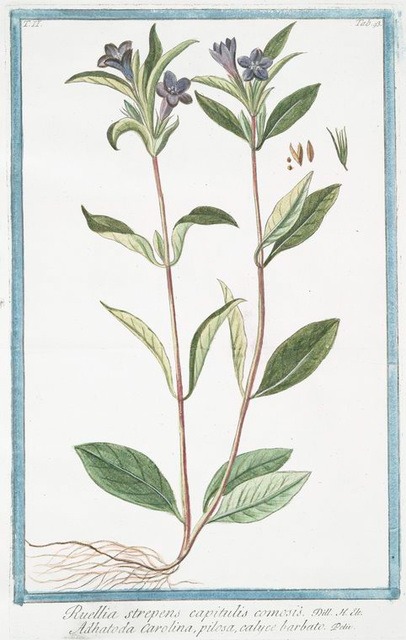

Our first submission of 2022 comes from Martha L. of Fort Worth. She submitted the photo to the right and the following information:

“This plant has been coming up in my yard in the Riverside area of Fort Worth, relatively near the river, for the last several years. It has small blooms that form in clusters at the base of the leaves. The blooms are white, tubular and look like long grains of rice. It grows to a height of about 20 inches. The leaves and stems die out in winter. It spreads very easily, appearing in all parts of the yard.”

The answer is (drum-roll, please): “Ruellia strepens, or smooth ruellia. Also known as limestone ruellia or wild petunia,” says Vice President of Research Peter Fritsch. “It is native to North America and grows across the South, Midwest, and Mid-Atlantic states.”

It’s a plant with some interesting characteristics. “Ruellia strepens is known to produce cleistogamous flowers,” says Fritsch.

Cleisto-what?

To explain cleistogamy, let’s first talk about its opposite, chasmogamy. Chasmogamy means “open marriage.” It is a term used to describe most flowers, which are, if you will, promiscuous. Flowers contain the reproductive organs of plants. They evolved to be colorful and showy to attract pollinators such as bees and butterflies. “This allows for cross-pollination and genetic variation,” says Fritsch. “This is a good thing for the plant, because genetic diversity promotes healthy stock.”

However, flower production requires a significant amount of energy. Making colorful petals and nutritious pollen is hard work. Some plants take a different approach. They produce flowers, but these flowers do not open, are not showy and bloom late in the growing season. Instead of attracting pollinators, the flowers pollinate themselves.

“With cleistogamous flowers, the plant reproduces non-sexually,” says Fritsch. This means the child plants carry the same genetic information as the parent plant, although shuffled around a bit. (The resulting children are not, therefore, exact clones of the parent plant—you can read about the difference between “selfing” and “cloning” here.)

This is the origin of the term cleistogamy, which means “closed marriage.” This approach has its downsides for the plant, since lack of genetic diversity can make plants more susceptible to pathogens and less competitive with invasive species. But so far it doesn’t seem to be doing Ruellia strepens any harm.

A familiar family of plants that often produces cleistogamous flowers is the genus Viola. including sweet violet (Viola odorata). In fact, many violas have both cliestogamous and chasmogamous flowers. Showy purple blooms appear in early spring, but in late spring the plant also produces small closed flowers near the base of the plant. The viola then produces two sets of seeds, one from cross-pollination and the other from self-pollination, thereby employing two strategies to maximize its reproductive potential.

American hog-peanut (Amphicarpaea bracteata) takes this approach a step further. It produces three types of flowers: One set of above-ground chasmogamous flowers, another set of above-ground cleistogamous flowers, and a third set of below-ground cleistogamous flowers. One research paper found that the seeds from these below-ground flowers were more than 30 times larger and produced more robust plants than the seeds from the other two types of flowers.

“Since these seeds are produced underground, the plant basically plants itself,” says Fritsch.

The hog-peanut has adopted a strategy called amphicarpy, our last botany term for the day. The term describes plants that produce two types of fruit, one type above-ground and one type below-ground. Plants use this strategy to increase the chance that their genetic material is passed on.

We’ve come a long way from a backyard in Riverside, but that’s one of the joys of botany—you never know what you’ll learn about the natural world from one plant.

Do you have a plant you need identified? We’ll play What Is This Thing once a quarter, and we’ll let you know a month in advance so you can submit your puzzling flower, grass, shrub or fungi. If you can’t wait that long, the BRIT Herbarium identifies plants all year long as a public service. Read more about it, including how to request an identification and the information we ask you to provide along with your plant. Thanks for playing What Is This Thing?