The bluebonnets are in bloom across North Texas, splashing waves of blue across hillsides and plains. Conditions this year were just right for brilliant displays of color, and you can expect to see families plunking their kids down in the middle of blooming patches for photos all weekend.

Learn more about bluebonnets

from the Garden’s own

Barney Lipscomb,

recently featured on CBS Texas.

Legends and Folk Tales

The wildflower was treasured by Texans for generations before the region became a state. Native Americans told several folk tales about bluebonnets. In one, recounted in the book Legends and Lore of Texas Wildflowers by Elizabeth Silverthorne, a tribe endured a devastating flood followed by severe drought and extreme heat. (Texans will immediately recognize these conditions.) Stores ran low, and the tribe grew hungry and desperate. They believed they had angered their god, and only by sacrificing their most beloved possession would they be forgiven and the rain return. A small girl heard the adults talking, crept out in the night and burned her dearly loved cornhusk doll. In the morning, the tribe awoke to find the landscape covered by blankets of bluebonnets–a promise of forgiveness and the return of rain.

Another legend dates to the time of Spanish colonization. It describes how a Spanish nun miraculously appeared to teach Christianity to the Jumano Indians. The nun habitually wore a bright blue cloak over her black habit. After her last visit to the Jumano, the people woke to find the land covered with flowers the color of her cloak as a reminder of her teachings.

The Botany of Bluebonnets

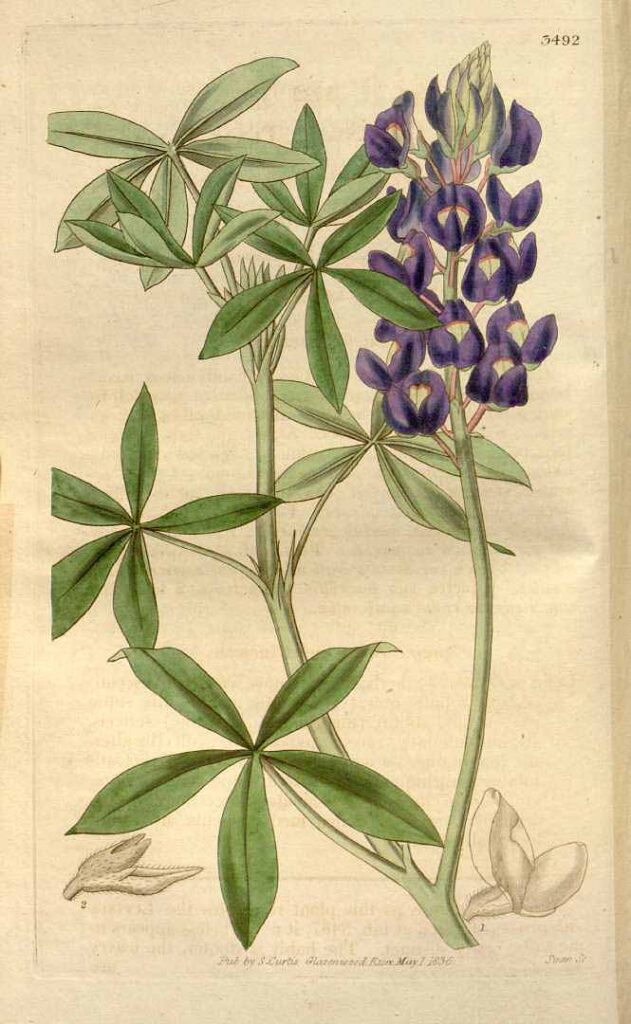

Botanists know bluebonnets as several species of flowers of the genus Lupinus. Lupines are found in the Mediterranean, North Africa, North America and South America, with about 270 species identified worldwide. The name “bluebonnet” has been applied to multiple different blue-flowering lupines in the southwest.

Bluebonnets depend on bees for pollination, and they have evolved features to attract pollinators, according to author Silverthorne. When the flowers first appear, a white spot appears on the upper petal. This spot attracts bees, who perch on the lower two petals to feast on pollen. However, bluebonnet pollen can quickly become infertile. Five days after blooming, the white spot turns magenta red, indicating to bees that the pollen within is no longer worth their while. Bees immediately ignore the magenta-spotted flowers. In other words, “The upper petal, or banner, has a white spot to signal a passing bee that dinner is ready and a red spot when dinner is finished,” wrote Jean Andrews in her book, The Texas Bluebonnet.

Bluebonnet seeds are covered in a tough coating that helps them survive difficult conditions. In fact, the seeds evolved so that only some–usually fewer than 20 percent–will germinate in any given year. A large percentage of seeds remain in the soil for future seasons, ensuring that the species will survive hostile weather. Conditions must be right to ensure a good spring showing–a frustration for Texans hoping for that burst of blue but a smart strategy for the plant to endure year after year.

The seeds that germinate do so in the fall and grow into small, ground-hugging rosettes. Below the rosette, the flower establishes a large root system that will sustain it over the winter. Bluebonnets must have moist soil to germinate, but from that point on they are highly drought tolerant. Warm weather prompts the plant to bloom.

Bluebonnets’ Magic Trick

Bluebonnets can grow in conditions most plants would find hostile, including rocky hillsides, worn-out farmland and alongside highways. The plant’s drought tolerance is a key factor in its hardiness, but bluebonnets also have a trick up their sleeves: they produce their own nitrogen.

The element nitrogen is essential for plants to grow and thrive. The development of a process to extract nitrogen from the air (what is known as “fixing” nitrogen) to produce fertilizer is one of the most significant scientific achievements of the twentieth century. Artificial fertilizer literally keeps the world population alive by allowing agricultural productivity that would otherwise be impossible. However, this process is enormously energy intensive and produces massive carbon emissions.

However, some plants don’t need artificial fertilizer. Legumes, including clover and alfalfa, evolved a symbiotic relationship with a bacterium known as Rhizobium. The bacterium lives in nodules on the roots of the plant, takes in nitrogen from the air and fixes it into a form the plant can use. When the plant eventually dies and decomposes, this nitrogen is released into the soil. It’s no muss, no fuss, one-hundred-percent natural fertilizer. Lupines, including bluebonnets, are also members of the legume family.

Growing legumes to replenish nitrogen-depleted soil is an ancient technique revived by organic farmers used around the world. So far, none of them seem to be using bluebonnets.

Bluebonnet season doesn’t last long–a month at most–so celebrate it while you can. You can find bluebonnets at several locations in the Garden, including in the Pollinator Pathway, along the BRIT building, in the Rose Garden and in the Trial Garden. Consider planting your own next fall, and think about all of the ways that plants enrich our lives.