It’s a fact so obvious that we named an entire season after it: fall leaves fall from trees. But what’s going on within the plant during that process? A lot more than you might think.

First, not all trees lose their leaves. In general, evergreens, usually conifers, keep their leaves or needles through the entire winter, while deciduous trees drop their leaves. “Deciduous” comes a Latin word meaning “to fall off.”

However, plant life is rarely as neat as the definitions we like to give it. Some conifers (trees such as spruces, firs and cedars) do, in fact, lose all of their needles in the fall, including bald cypress trees (Taxodium distichum).

And some deciduous trees hold on to their leaves through the winter. Live oak trees (Quercus virginiana) are so named because they remain “alive” with leaves through the winter. However, these deciduous trees usually loose their leaves later–they drop last season’s leaves in the spring when new leaves appear. (Botanists call this “marcescence.”)

Back to the question of why. It’s all about energy. Leaves are the energy generators of trees, producing energy through photosynthesis. Some of that energy must be dedicated to supporting the leaves themselves, by, for example, supplying them with water and nutrients.

In the summer, when sunlight is plentiful, leaves produce far more energy than is needed to sustain them.

But when the seasons shift and days grow shorter, leaves will only be able to produce a small amount of energy. Leaves start to cost more than they are worth. It’s more efficient for the tree to lose the leaves and go dormant until spring.

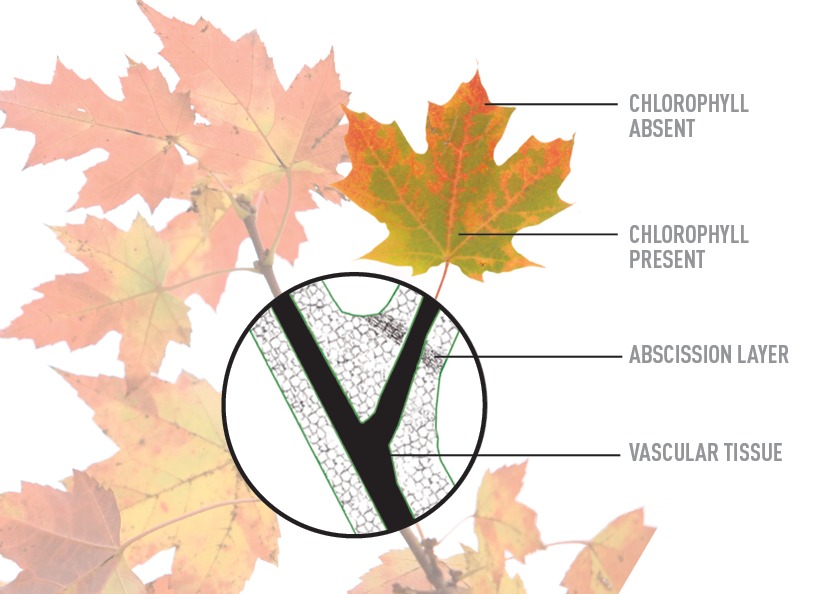

The process of entering dormancy is called “senescence,” and the first step is for the tree to stop producing chlorophyll, the molecule involved in photosynthesis. However, previously existing chlorophyll will remain in the leaves, and that molecule contains valuable nutrients such as nitrogen–nitrogen that the tree doesn’t want to lose. Trees actually pull these nutrients from the chlorophyll to use elsewhere in the tree. Waste not, want not.

Chlorophyll is bright green, so as the amount of the molecule within the leaf decreases, the color of leaves changes from green to varieties of yellow, orange and red produced by other chemicals in leaves. These chemicals were in the leaf all along, but the chlorophyll made them impossible to see.

At the same time leaves are changing color, other chemical changes are taking place at the point where the leaf petiole meets the stem of the tree. A petiole is the stalk that attaches a leaf blade to a stem.

At this point, an “abscission zone” is formed. “Abscission” comes from the same Latin root as the word “scissors,” because this zone cuts the petiole from the tree. At this zone, a layer of tough, waterproof cells forms that will protect the tree from damage when the leaf falls.

The tree then makes the final cut. Different trees employ different mechanisms to detach their leaves. Some secrete enzymes that break down the walls of the cells holding the petiole to the stem, slowly separating the two. Others flood the cells on the leaf side of the abscission zone with water. These walls swell and eventually burst.

At this point, a light breeze, a drop of rain or even gravity can send the leaves plummeting to the ground.

For most trees, abscission layers form gradually over time, so that leaves fall over the course of days or weeks (barring heavy winds that might strip a tree of leaves overnight).

However, one tree likes to do things its own way. Gingko trees (Ginko biloba), those fascinating living fossils, lose all of their leaves at once.

The process isn’t fully understood, but it seems that the first hard frost of the year will trigger gingko trees to form abscission layers on all of their leaves at the same time. On a single day, a ginko will drop all of its leaves, a sight that people have compared to a heavy snowfall of golden leaves.

Fall leaf colors can be more dramatic some years than others. It’s a complex process determined largely by the weather over the course of the entire growing season. Drought early in the season can dampen colors; a heat wave in August can scorch leaves to the point that they drop early.

The record high temperatures this summer likely mean this won’t be a banner year for fall color, but don’t write off the possibility.

The Japanese maples in the Japanese Garden almost always put on a grand show, thanks to the high amounts of anthocyanins in their leaves. Anthocyanins are pigments that may appear red, purple, blue or black. The dark purple of pansies and the velvety blues of blueberries are also brought to you by anthocyanins.

Our horticulturists expect the maples to be at their best between now and Thanksgiving, so make sure you plan a visit. And when you see leaves fall, you will know a tree has successfully completed abscission for another year.