Important botanical science happens in the field. Researchers tramp across habitats, sometimes in remote and rugged regions of the world, collect plant samples, document the distribution of species and study ecosystems in action.

Later those scientists return to the lab with boxes of specimens, and a new and equally important phase of research begins. Scientists label, mount and digitize specimens to make them accessible to the global science community. They become a resource that can be studied in multiple contexts–as part of an ecosystem or as a member of a particular plant family, for example.

“If specimens are just sitting in a cabinet, only the people with access to that cabinet can study them,” says Herbarium Collections Manager Ashley Bordelon. “When we upload photos of the specimens and all of their associated data, scientists across the world can use that information to make real discoveries.”

This work can take years, and community scientists can play a critical role–even from the comfort of their own homes. An upcoming online forum will discuss one field project and how volunteers can help make the data collected from similar projects available worldwide.

Amazon to Andes and Back to Fort Worth

The Andes to Amazon Biodiversity Program (AABP) operated from 2007 to 2011 and involved scientists from BRIT alongside researchers from Peru, and the specimens collected continue to serve as primary sources of information about neotropical biodiversity. The focus of the project was the region in South America that reaches from the eastern slopes of the Andes Mountains meet the Amazonian lowlands.

Armchair Botanist Forum –

Exploring Peru’s Breathtaking Flora:

Discoveries from the Andes to Amazon

Biodiversity Program

Sept. 14, 12 – 1 pm

“This area harbors one of the greatest concentrations of botanical diversity on earth,” says Herbarium Director Tiana Rehman, who worked in Peru on the AABP. “It includes grasslands, cloud forests, swamps and bogs–it’s extraordinary.”

The collaborative team investigated the biodiversity of the region and studied the interactions of animals, insects and plants. The research was funded by sponsors including the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI) Conservation Program, the Discovery Foundation, the Moore Foundation and private donors.

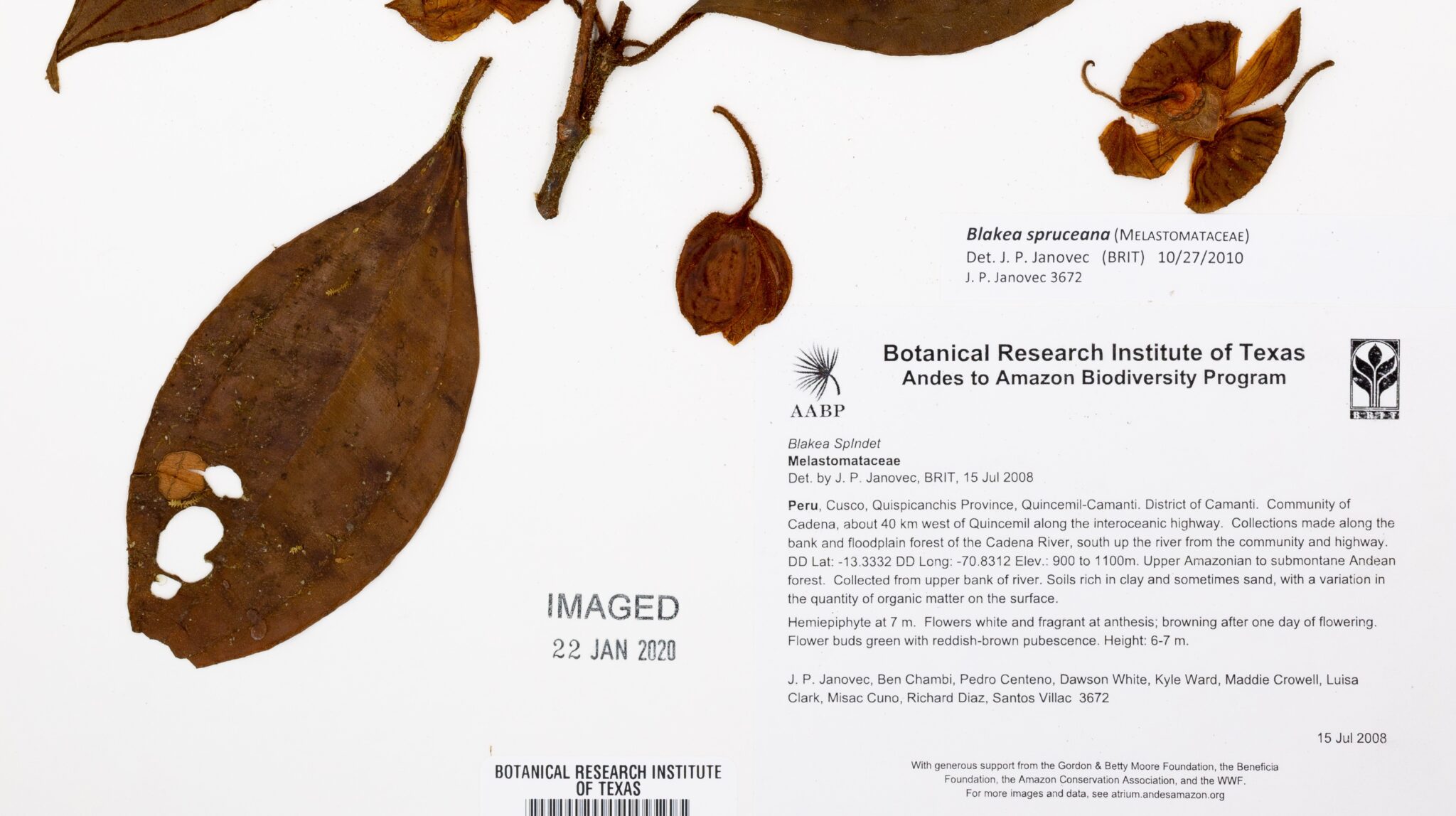

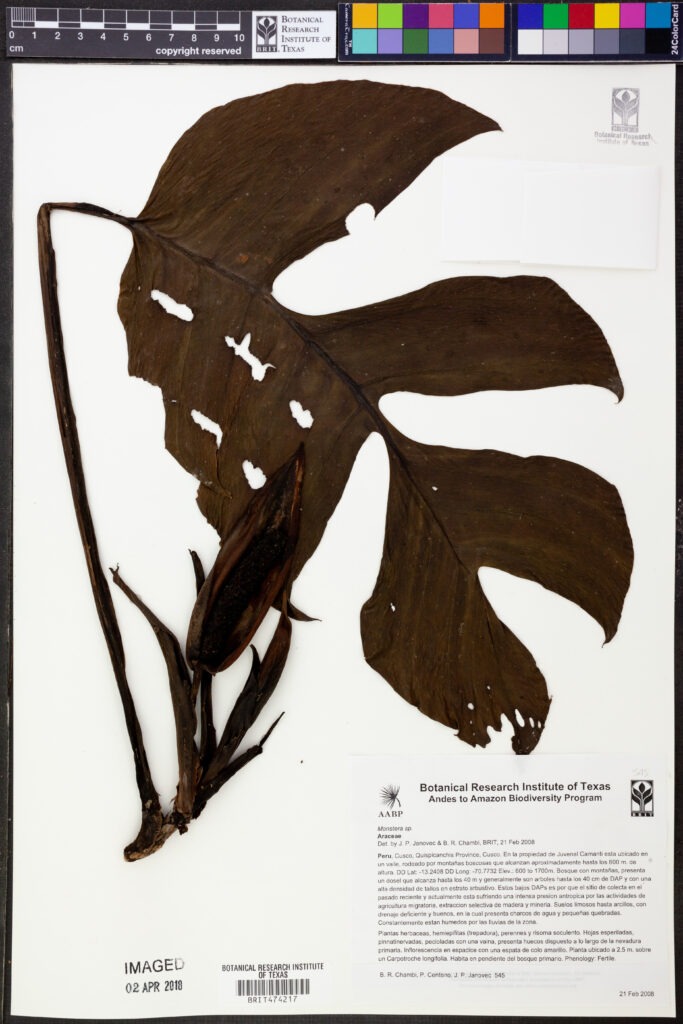

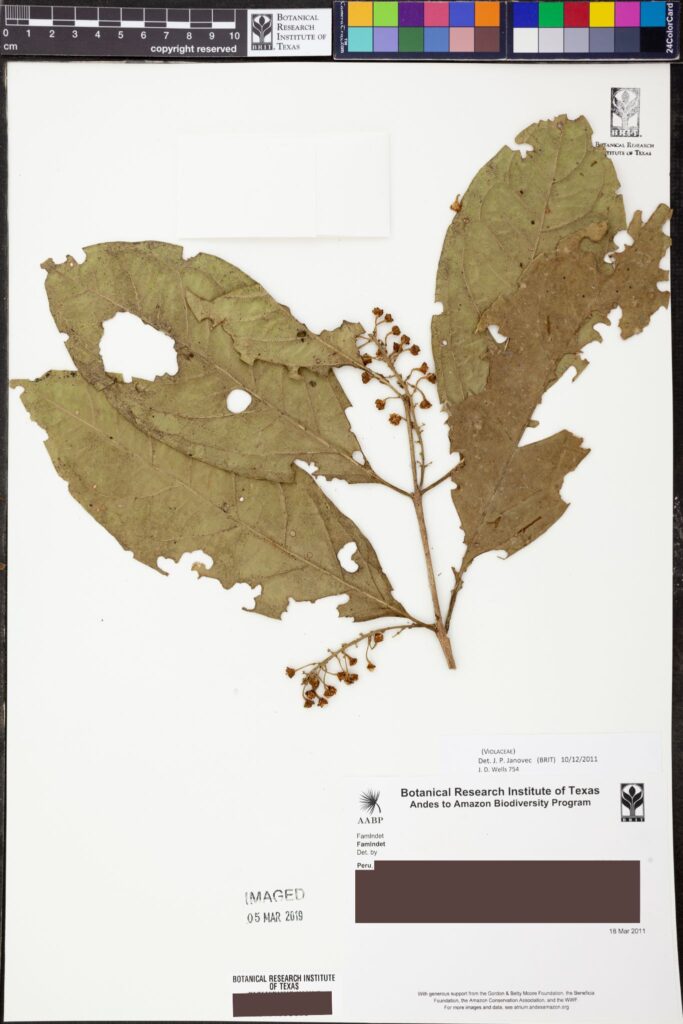

Specimens of more than 7000 individual plants were collected over the course of the project, mounted on cardstock and added to the Herbarium. These specimens have been digitized–that is, they have been digitally photographed at high resolution–and more than 3000 of these records are available on the TORCH Portal (the online searchable database that includes BRIT specimens.) The Herbarium team continues to enter new identifications received from botanists around the world and make all of the records available online.

Herbarium specimens and other data collected during the project will be studied by scientists for years to come. Already, at least 38 papers citing the AABP have been published on topics ranging from “Climate Change versus Deforestation: Implications for Tree Species Distribution in the Dry Forests of Southern Ecuador” to “Spiny but Photogenic: Amateur Sightings Complement Herbarium Specimens to Reveal the Bioregions of Cacti .”

Making Data Accessible Makes Discoveries Possible

Why is it so important to not only collect specimens but also put this information online and make it available to anyone? Because that’s how new discoveries are made.

Scientific research is based on data, and each specimen can be viewed as a collection of thousands of data points. When a subset of that data is available online and searchable, scientists can find meaning.

For example, each specimen is associated with a label that contains essential information on the name of the species, who collected it, and exactly when and where it was collected (including the elevation).

This information provides the critical context for each specimen. For example, scientists might realize a plant was discovered somewhere it had never been found before and therefore has a wider distribution than previously believed. They might correlate information on the date of collection with climate data and realize the plant only blooms under particular conditions. They might be able to associate the species with a particular insect or bird and better understand the ecosystem as a whole. Or they could discover differences between this specimen and previously collected specimens and realize they have identified a new species.

“Different researchers will look at specimens from different perspectives and ask different questions,” says Rehman. “The questions will change over time and as new technologies become available. The tools available today to study plants would be unimaginable to botanists two hundred years ago.”

The Critical Role of Volunteers

To make the data from these collections available, they must be digitized–and that’s where volunteers play a crucial role. While digitization has been streamlined and automated as much as possible, a human being still needs to transcribe the data on a specimen label–that is, read and enter that data into the database.

The AABP collection is only one of many that the Herbarium is seeking to digitize. In fact, it is in a better state of digitization than many other collections. “Our other collections are worldwide in origin, encompass hundreds of plant families, and were collected as early as the 1800s,” says Rehman.

The work isn’t hard, but it requires patience and precision, and training is necessary. But many volunteers find it rewarding to dive into the details of a region and its plant life. They also enjoy contributing to science at their own pace on their own time. “A lot of the work is online, so people can do it anywhere, anytime,” says Bordelon. “That’s what the Armchair Botanist program is all about.”

Rehman and Bordelon host monthly virtual meetings for Armchair Botanists where they answer questions and hold transcription blitzes. The meetings also usually include a presentation; the Andes to Amazon Biodiversity Program will be the topic of the September session. You can explore previous sessions online.

Celebrating the Biodiversity of Latin America

As the Garden explores the culture and heritage of Latin America this month at ¡Celebramos!, the Herbarium team saw an opportunity to also recognize the unique plant and animal life of a particular region of South America.

The project also highlights the responsibility the team feels toward research conducted in another country, in this case Peru.

“As well as bringing home specimens, duplicate specimens were deposited in Peruvian herbaria. But putting the records online means that students and researchers from all over the world can access them,” say Rehman. “That means people without funding or the time to travel can still access this data. And this data is important to the management and conservation decisions being made today. We feel a responsibility to do that.”

The upcoming virtual Symphyotrichum oblongifoliumsession will be an introduction to the Armchair Botanist program, as well as an opportunity to learn how work in the field leads to work in the lab and herbarium–work that continues to advance understanding of the role of plants on the planet.