The poinsettia is a quintessential part of typical holiday decor. Its bright red, burgundy, or white foliage are common sights in locations both private and public throughout the winter months, from apartment balconies and church altars to bank lobbies and coffeehouses.

It’s a plant with a curious history that stretches from the Aztecs to a pioneering American diplomat and a family of plant-savvy Californians.

Ancient Aztec Beginnings

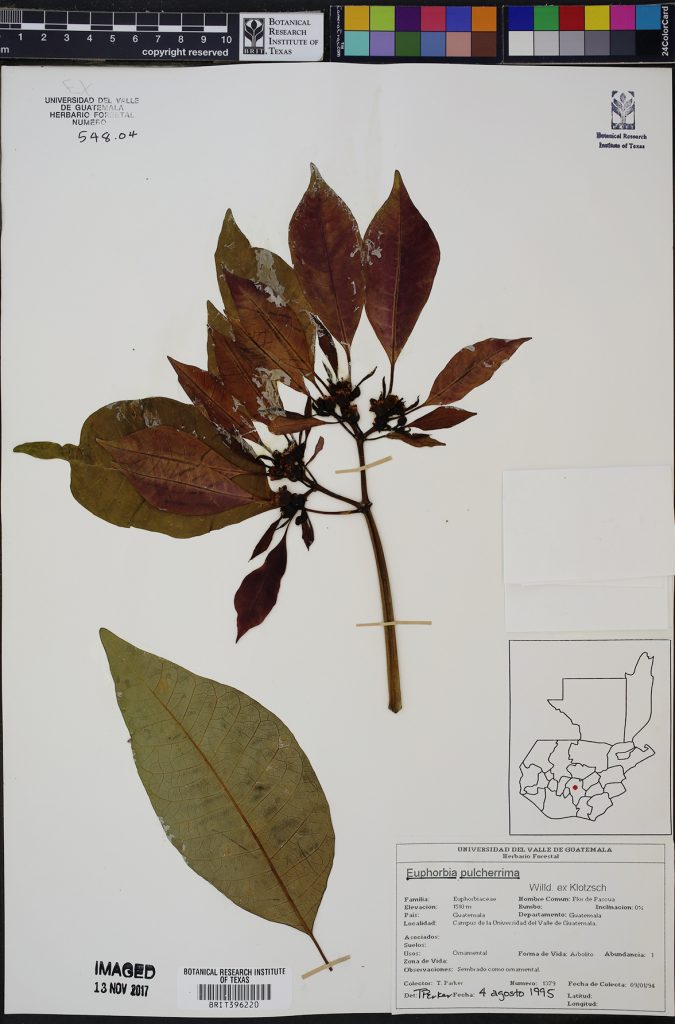

Before they were known as poinsettias, Euphorbia pulcherrima was known as cuitlaxochitlI to the Aztecs, which translates to something like “‘flower that grows in residues or soil.” Indigenous people used the plant as a source for dyes and fever-reducing medicine.

The plant is native to mid-elevation dry forests from Mexico to southern Guatemala on Pacific-facing coasts. Poinsettias grow as shrubs or small trees that can reach up to 13 feet tall. The flowers of the poinsettia are actually small and unassuming; its color comes from its bright red leaves.

These colorful leaves are created through a process called “photoperiodism,” which is a reaction of the plant to the length of night hours. Poinsettia is a type of short-day plant, meaning it responds when nights reach a certain length. Poinsettias require at least fourteen hours of darkness six to eight weeks in a row for their leaves to turn red.

Following the arrival of the Spanish in Mexico and Guatemala, the red blooms became associated with Christmas, and the plant was given the new name, “Flor de Noche Buena” or Christmas Eve Flower. One 16th century Christian legend tells a story about a young girl, too poor to provide a gift for Jesus, who was inspired by an angel to pick weeds and form a bouquet. After placing the bouquet on her church’s altar, the weeds became crimson blossoms and turned into poinsettias.

A New Name for a New Market

Poinsettias arrived in the U.S. thanks to the work of a single diplomat: Joel Roberts Poinsett, the first U.S. envoy to the recently established Mexican Republic in 1825. Poinsett was also an amateur botanist, and he became enamored with a shrub he noticed growing in a suburb near Mexico City. He sent samples of the plant to his greenhouse in South Carolina and widely distributed cuttings to friends. By 1836, E. pulcherrima was known popularly in the United States as poinsettia.

However, it took a family of enterprising Californias to cement the association of poinsettias with Christmas in the United States. The story begins with Albert Ecke, a German immigrant who moved to Los Angeles in 1900 and sold poinsettia cuttings from a street stand as a side business.

Albert’s son Paul, later known as the Poinsettia King, was both a keen businessman and a talented nurseryman. He developed a special grafting technique that created potted poinsettias with an attractive bushy appearance–the poinsettias we know today.

Then Paul’s son, Paul Ecke Jr., widely advertised poinsettias by providing free decorations for national television shows and holiday specials. He became a regular feature on “The Tonight Show” and Bob Hope Christmas specials extolling the virtues of poinsettias.

For many decades, the Ecke family held a monopoly over poinsettias, like DeBeers to diamonds, and the secret of their grafting technique was known only to a handful of family members and the head horticulturalist.

However, in 1991 a university researcher discovered and published the technique. Rival growers began to steal market share thanks to cheap labor in South America. The price of poinsettias dropped dramatically. The Ecke family sold their business 2012; while the Ecke Ranch continues to sell poinsettias and holds roughly 50 percent share of the market, its plants are now grown in Guatemala. (Curiously, Mexico is barred from exporting poinsettias to the United States, the result of a century-old ban on bringing soil from Mexico into the United States. Not surprisingly, Mexican growers want this rule changed.)

The Economic Power of a Single Plant

Americans buy more poinsettias than live Christmas trees, although trees generate more revenue. Each year in the US, approximately 70 million poinsettias are sold in a period of six weeks, at a value of $250 million.[36] This makes the poinsettia the world’s most economically important potted plant.

One final point about this holiday favorite: is it pronounced “poin-set-ta” or “poin-set-ti-a”? When the plant was first introduced by Poinsett, it was called “poin-set-ti-a,” and some Americans stick with that pronunciation today. However, over time “poin-set-ta” has become so widespread that it is now considered an acceptable variation.

Whatever you call it, as you enjoy the bright, cheerful colors of poinsettias this December, consider the long, eventful journey of this fascinating plant and all of the ways that the natural world enriches our lives.