The Sweep of Time

Article originally submitted for The Leaflet (June 2014) by Brian Witte, PhD, BRIT Research Associate

Most of us live in the moment. Paycheck-to-paycheck, living for the weekend, summer vacation, twitter updates. Updates now are measured in seconds. America, too, is a young nation. Few places west of the Appalachians boast buildings over 150 years old, and most of us live in suburbs built in the decades following World War II. So much around us is new…even our landscapes are new, transformed by mechanized farming, car culture, and introduced species.

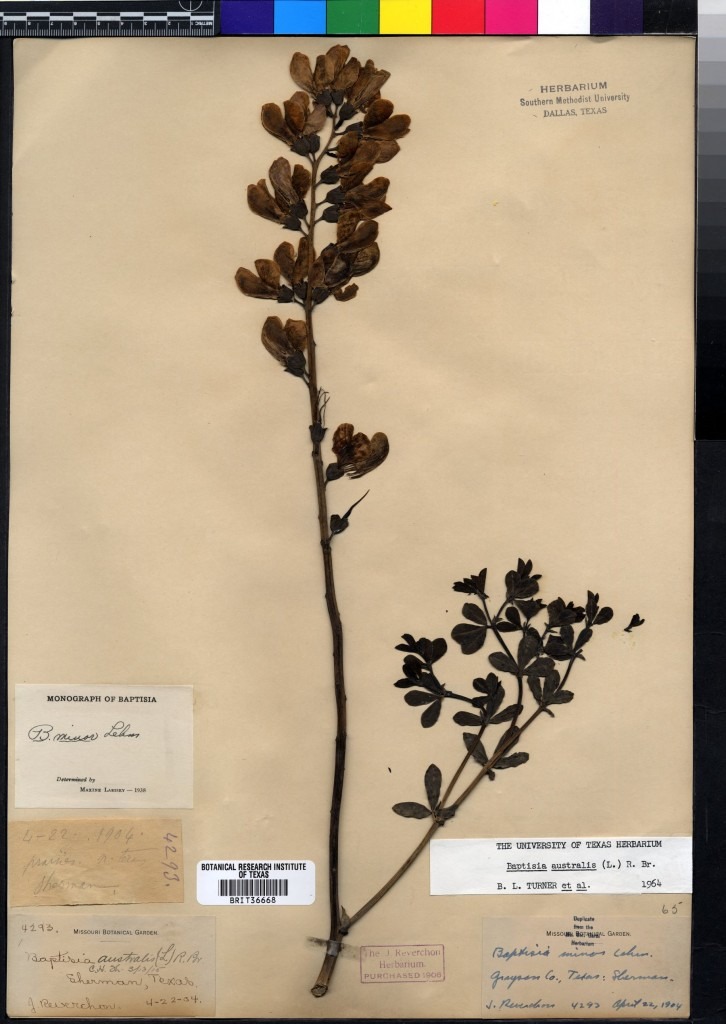

That’s not entirely news, and it’s not entirely new, either. Look, for example, at this sheet I recently encountered while tidying up a database of digitized herbarium specimens.

Click to enlarge and read labels.

This was one of the last collections by Julien Reverchon, a pioneering botanist in Texas. His collection of 20,000 specimens, many of which are held at BRIT, are some of the first collections from the Southwest, and many of them played an important role in early floras produced in the golden age of American Natural History. There is a lot of history that could be read just from this one specimen. In this case, however, it is the date (at the bottom left corner) noted by a curator at the Missouri Botanic Garden that drew me: 4-22-04. When the data for this specimen was entered verbatim in to our online database, the software “autocorrected” the date to April 22, 2004. The discrepancy between the collector, who died in 1905, and the putative collection date of a scant 10 years ago, caught my eye and the error was fixed.

I was reminded of this archival error later when I was annotating specimens for my own project at BRIT. I wrote on a freshly printed annotation label: Astragalus mollissimus var. bigelovii det. Brian Witte 4/15/14. And suddenly the gulf of centuries opened before me. Someone in 2114 may look at this specimen and chuckle at the short-sightedness of that Brian fellow in thinking that “14” would of course refer to 2014…just as “04” referred to 1904.

I am sure that any collector who has contributed to a herbarium has thought of his or her work as a gift to posterity, but I doubt very much that many of us have thought in terms of centuries. Even those of us who delight in reading books on history imagine that we, ourselves, will one day be just the history that others read.

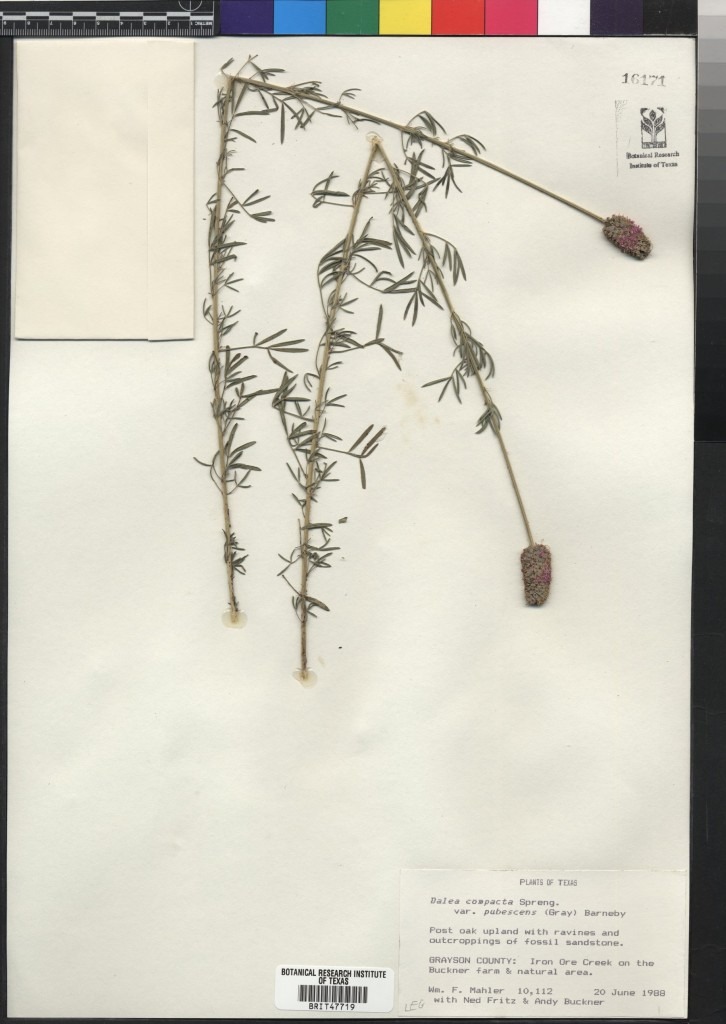

Now that I am aware of this focus on immediate, I see evidence throughout the collection. Annotations abbreviated LHS mean they were added by Lloyd Herbert Shinners, the former curator of the herbarium. LEA, however, collected several dozen specimens in the 1960’s, and I have been unable to ascertain his or her full name. Doubtless the herbarium director at the time knew, but that knowledge may have died with him. Witness, too, the references to locations long since gone or atrophied into nothingness. One example:

William Mahler, the collector and past director of the herbarium, may well have known where the Buckner Farm was, and he would no doubt have gladly told you. The opportunity, however, has passed.

I am hardly the first to have realized these challenges. Our data entry protocols now require four digit years, standardized spelling for the names of collectors (no more three letter abbreviations), and locations given in GPS-compatible coordinates accurate to within a meter.

And yet, I wonder what our descendants a millennium from now will think when they chance upon an archaic collection of data and think “2014…I wonder what calendar they were using back then?”