Field log:

A specimen is only scientifically useful if it is accompanied by collection notes regarding where, when, and under what circumstances a plant was collected. In order to keep track of this information, a collector will carry a field log in which to jot down notes. Since a collector might collect many plants over a lifetime of work (in some cases, well over 70,000!), he or she needs a reliable way to tie the plant specimen to the notes in their field log. Most botanists use a unique identifying number for each collection. The best system of collection numbers to use is consecutive numbers. We all have to start at “1”. Each number should refer to one collection and should never be repeated. In this way, the collector’s name and the collection number together become a unique designator for a specimen. For example if Amanda K. Neill was making her 1000th collection, the code she would identify with that specimen would be “A.K. Neill 1000”. Note that all duplicates (parts of the same plant) as well as individual specimens with multiple sheets should bear the same number.

The collection number is recorded in the field notebook at the time of collection together with information about that collection. At minimum, the following data should always be included in your field log, for each collection:

Collector’s name and collection team: the first name listed is considered the primary collector. e.g. A.K. Neill, T. Franklin and B. Byerley

Collection number: this should be the primary collector’s record number.e.g. 1000

Collection Date: it is useful to spell out the month, or use roman numerals to denote the month to prevent any miscommunication. e.g. 27 April 2009, or 27.IV.2009

Precise locality: country, state, county, town, miles and direction from a town or street intersection, latitude and longitude, and altitude. This should be detailed enough such that someone could find his way back to your exact spot. e.g. U.S.A., Texas, Tarrant Co., Fort Worth, Todd Island trail system. Fort Worth Nature Center and Refuge. 32° 51.152 N, 97° 29.288 W, elevation 595 ft.

Further information that would also be of use includes, but is not limited to:

Plant description: record features which will not be evident from the pressed specimen such as color, odor, sap or latex, height, DBH (diameter at breast height -1.37m above soil line). Special attention to describing the flowers and leaves.

Habit: the form of the plant, either herb, shrub, tree, or vine (or intermediate category). Associated species and vegetation type: this will give the herbarium user an indication of whether the plant was growing in a post-oak forest, on prairie, or in a riparian area. You might include an estimation of forest height and density.

Habitat: type of soil (sand, clay, loam), topography, slope, exposure, amount of sun, proximity to water source such as a stream, etc.

Cultivated/escaped: herbaria often rely on plants that grow naturally in an area, so it’s important to distinguish between wild species growing naturally and those grown after human intervention, such as exotic plants that may have escaped from a garden.

Level of disturbance: land use, such as natural or agricultural.

Ecological notes: this might include notice of insect damage, visits by insects/animals (pollination), covered in vines, weather damage/lightning strike. This might also include use by local peoples, common names, or other forms of cultural knowledge surrounding that specimen.

When pressing each specimen, record your name and collection number on the margin of the newspaper.

Photography:

It is extremely important to note all those observations that may change with time (e.g. flower color, presence of hairs on stems, size of fruit) or that will be unavailable when that specimen is deposited in a herbarium (e.g. soil type, proximity to water, elevation). However, photography presents another medium in which to document a plant collection. In some cases the photograph is attached to the plant specimen or included in a publication, and increasingly, online databases are serving as a repository for these images (e.g. atrium.andesamazon.org). Regardless of the manner in which they are tied to the specimens, photographs serve to document the habitat and the plant proper.

Objectives that should be kept in mind when photographing are to include a picture of the habit (growth form) of the plant, of the under- and top-sides of the leaves, a close-up of any reproductive material (fruits or flowers). Photographs of the insects visiting the plant or close-ups of material that could be taxonomically important should also be taken.

Making a plant database:

Herbaria around the world are in the process of digitizing their collections in order to make the data represented by a plant collection available for viewing and analysis via computers. One of the major culprits shortening the lifespan of plant specimens is excessive handling, and through the use of high resolution cameras and scanners, we attempt to preserve a digital record of each specimen in the form of an image and a database of label data. This digitization is not intended to replace a specimen, for an image cannot be handled dissected or looked at under a microscope, but rather is intended to supplement a collection.

A database can be used to record research collection data and to produce printed labels that will be mounted on the herbarium sheet with the plant specimen. Common personal databases often use readily available programs such as Microsoft Access or Microsoft Excel, but some databases can be more involved and utilized via a shared online system (e.g. atrium.brit.org).

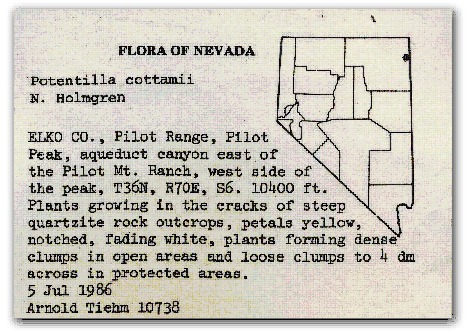

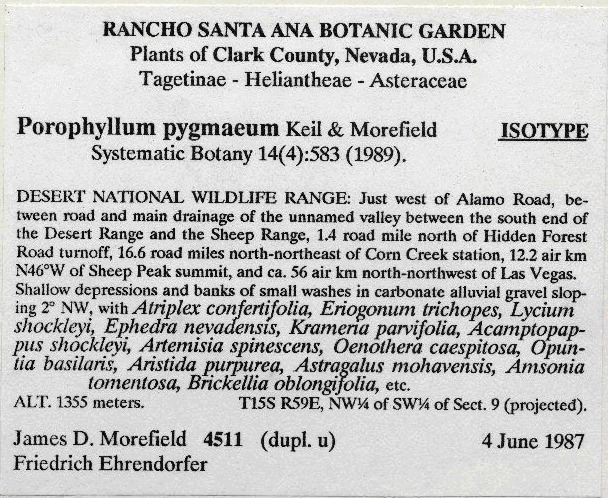

Specimen label:

Plant labels are created with the information from the field log. They should be printed on acid-free paper and should accompany the specimen prior to mounting, while it is still stored between newspaper. Below is a typical format for a specimen label.