Plant Collection and Preservation

Preserved plant specimens provide invaluable evidence of plant diversity and distribution, offering a verifiable record of a species’ presence across time and space. When properly stored, these specimens can last for more than 200 years, serving as critical repositories of information, particularly in an era of rapid habitat loss. Herbaria ensure this material remains available for future research, allowing scientists to study biodiversity changes, verify plant identifications, and draw conclusions about ecological trends.

Plant collections are made by botanists, researchers in other fields, and citizen scientists to document their work and interests.

Whenever a plant is part of a research project, best practice dictates creating a voucher specimen that will be deposited in a herbarium. This not only supports the original study but also provides a resource for other researchers who may need to confirm the plant’s identity or gather additional data.

Specimen collection typically involves gathering plants in the field, pressing them between newspapers, and drying them in a plant press. During this process, collectors record essential information—such as the plant’s presumed identity, collection date and location, habitat characteristics, soil type, and associated species—in a field log. Noting details like flower color, scent, and growth habit is especially important, as some attributes may not be evident in the dried specimen.

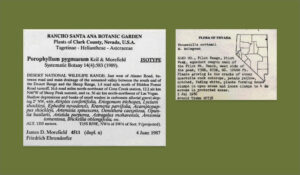

Once dried, the specimen is mounted on acid-free paper and labeled with its name, classification, and all relevant collection data. These mounted sheets are stored in specialized cabinets, organized by taxonomic group and geographic origin. With proper preservation methods, herbarium specimens remain scientifically valuable for centuries, providing a lasting foundation for botanical research and conservation efforts.

A How-To Plant Collection and Preservation Guide

-

What to collect

Be conservative and collect only what you need. It is a good idea to use the following rule of thumb: never collect a plant when you can see fewer than 6 individuals in the area. Select vigorous, typical specimens. Avoid insect-damaged plants. Make sure the plant has flowers and/or fruits. It may be a good idea to collect extra flowers and fruit for identification purposes. Sterile plants are very difficult to identify.

Roots, bulbs, and other underground parts of herbaceous (non-woody) plants should be carefully dug up, and the soil removed with care. When collecting shrubs and trees, clip one or two small branches. For each specimen you intend to collect, gather sufficient material to fill a herbarium sheet (11″ x 17″) and still leave enough room for the label. Plants too large for a single sheet may be divided and pressed as a series of sheets.

It is good practice to collect in duplicate. This means that if possible, you should collect sufficient material to make more than a single herbarium specimen. This serves multiple purposes: 1) as an insurance policy in case one specimen were to be lost or damaged, 2) allows you to then send one of the duplicates off to a botanical expert for identification, in which case this is commonly done as a gift to their herbarium, and 3) if you intend to export your collections from a country, it is often required that you first deposit a duplicate in that country’s national herbarium.

Note: If you are not able to press specimens during collection, place them in a labeled plastic bag (see field log section below for information on collection number) and add a sprinkle of water.

Where to collect

A choice of collecting locality depends on the purpose behind your collection. If you are collecting specimens to donate to a local herbarium, your backyard may not be an ideal choice. Most local herbaria specialize in native and naturalized plants and have fewer collections of hybrids and varieties that are bred specifically for the horticulture industry and generally are not seeking specimens of these plants. Some good locality choices might be undeveloped lands or areas that are not maintained and are likely to contain plants that have adapted to survive on their own in the “wild”. However, if you are interested in creating a herbarium for your own purposes then it is entirely up to you to choose where and what to collect. It is a good idea however to always obtain permission from the owner of any property on which you intend to collect plants, and be aware that collection in National Parks and preserves is likely only possible with special permission.

If you intend to collect plants outside of the United States, be aware that most countries require you to obtain a special plant collecting permit. It is always best to contact the national or local herbarium closest to your chosen collection location and request their advice with these permitting procedures. Note that most countries will require an export permit if you wish to ship the specimens back to the United States and that the United States requires an import permit. Herbaria are equipped to deal with transactions such as these and can be of immeasurable assistance with these logistics.

-

Field log

A specimen is only scientifically useful if it is accompanied by collection notes regarding where, when, and under what circumstances a plant was collected. In order to keep track of this information, a collector will carry a field log in which to jot down notes. Since a collector might collect many plants over a lifetime of work (in some cases, well over 70,000!), he or she needs a reliable way to tie the plant specimen to the notes in their field log. Most botanists use a unique identifying number for each collection. The best system of collection numbers to use is consecutive numbers. We all have to start at “1”. Each number should refer to one collection and should never be repeated. In this way, the collector’s name and the collection number together become a unique designator for a specimen. For example, if Amanda K. Neill was making her 1000th collection, the code she would identify with that specimen would be “A.K. Neill 1000”. Note that all duplicates (parts of the same plant) as well as individual specimens with multiple sheets should bear the same number.

The collection number is recorded in the field notebook at the time of collection together with information about that collection. At minimum, the following data should always be included in your field log, for each collection:

Collector’s name and collection team: the first name listed is considered the primary collector. e.g. A.K. Neill, T. Franklin, and B. Byerley

Collection number: this should be the primary collector’s record number . e.g. 1000

Collection Date: it is useful to spell out the month, or use Roman numerals to denote the month to prevent any miscommunication. e.g. 27 April 2009, or 27.IV.2009

Precise locality: country, state, county, town, miles, and direction from a town or street intersection, latitude and longitude, and altitude. This should be detailed enough such that someone could find his way back to your exact spot. e.g. U.S.A., Texas, Tarrant Co., Fort Worth, Todd Island trail system. Fort Worth Nature Center and Refuge. 32° 51.152 N, 97° 29.288 W, elevation 595 ft.

Further information that would also be of use includes, but is not limited to:

Plant description: record features that will not be evident from the pressed specimen such as color, odor, sap or latex, height, and DBH (diameter at breast height -1.37m above the soil line). Special attention to describing the flowers and leaves.

Habit: the form of the plant, either herb, shrub, tree, or vine (or intermediate category). Associated species and vegetation type: this will give the herbarium user an indication of whether the plant was growing in a post-oak forest, on the prairie, or in a riparian area. You might include an estimation of forest height and density.

Habitat: type of soil (sand, clay, loam), topography, slope, exposure, amount of sun, proximity to a water source such as a stream, etc.

Cultivated/escaped: herbaria often rely on plants that grow naturally in an area, so it’s important to distinguish between wild species growing naturally and those grown after human intervention, such as exotic plants that may have escaped from a garden.

Level of disturbance: land use, such as natural or agricultural.

Ecological notes: this might include notice of insect damage, visits by insects/animals (pollination), covered in vines, weather damage/lightning strikes. This might also include use by local peoples, common names, or other forms of cultural knowledge surrounding that specimen.

When pressing each specimen, record your name and collection number on the margin of the newspaper.

Photography

It is extremely important to note all those observations that may change with time (e.g. flower color, presence of hairs on stems, size of fruit) or that will be unavailable when that specimen is deposited in a herbarium (e.g. soil type, proximity to water, elevation). However, photography presents another medium in which to document a plant collection. In some cases the photograph is attached to the plant specimen or included in a publication, and increasingly, online databases are serving as a repository for these images (e.g. atrium.andesamazon.org). Regardless of the manner in which they are tied to the specimens, photographs serve to document the habitat and the plant proper.

Objectives that should be kept in mind when photographing are to include a picture of the habit (growth form) of the plant, of the under- and top-sides of the leaves, and a close-up of any reproductive material (fruits or flowers). Photographs of the insects visiting the plant or close-ups of material that could be taxonomically important should also be taken.

Making a plant database

Herbaria around the world are in the process of digitizing their collections in order to make the data represented by a plant collection available for viewing and analysis via computers. One of the major culprits shortening the lifespan of plant specimens is excessive handling, and through the use of high-resolution cameras and scanners, we attempt to preserve a digital record of each specimen in the form of an image and a database of label data. This digitization is not intended to replace a specimen, for an image cannot be handled dissected, or looked at under a microscope, but rather is intended to supplement a collection.

A database can be used to record research collection data and to produce printed labels that will be mounted on the herbarium sheet with the plant specimen. Common personal databases often use readily available programs such as Microsoft Access or Microsoft Excel, but some databases can be more involved and utilized via a shared online system (e.g. atrium.brit.org).

Specimen label

Plant labels are created with the information from the field log. They should be printed on acid-free paper and should accompany the specimen prior to mounting, while it is still stored between newspaper. Below are typical formats for a specimen label.

-

Pressing

In order to facilitate the storage and use of plant specimens, the procedure of pressing plants flat to be mounted on cardstock has arisen. When you are ready to press your plant, consider what you want the dried specimens to look like. All the “valuable information” has to be visible from a single side, since the other side will be glued to paper. Make sure both sides of the leaves are visible, and turn flowers/fruits in various directions so the fronts, sides, and backs of them are visible.

Long, slender plants can be folded in a zigzag fashion or clipped in strategic locations to fit inside the newspaper sheet. Bulky parts and fleshy fruits can often be halved or sliced before pressing. Odd fragments (bark or large hard fruits) should be kept in numbered or labeled envelopes or packets with the main specimen.

Building your own plant press:

Specimens are pressed in a plant press, which essentially consists of a rigid frame, cardboard, blotter paper and folded newspaper but can be as simple as an extra telephone directory! The objective of the plant press is to flatten and evenly dry the plant specimen so that it may best be mounted and preserved on a sheet of hard cardstock while still retaining its morphological characters. Plants properly pressed, dried, labeled, and mounted can be stored indefinitely as a record of the flora. The equipment is simple and can be improvised. You will need a plant press and newspaper to hold the specimens. Plant presses can be purchased* or improvised. A recent article was published in the Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas detailing the design for a field press—please find this article attached in the appendix.

To build a general plant press you will need:

- 2 pieces of board of equal size at least as large as a folded newspaper: 12″ x 16″ (boards with holes for ventilation or lattice frames are ideal)

- Pieces of corrugated cardboard as ventilators (the same size as the boards/frames)

- Absorbent paper (folded newspaper, paper towels, or blotter paper)

- Foam (optional)

- Newspaper

- Rope, belts, or webbing straps to hold the press together OR several heavy books to weigh down the stack of pressed specimens.

When pressing, alternate layers thusly: cardboard, absorbent paper, a folded newspaper with the plant pressed inside, absorbent paper, cardboard…etc. Place the stack between the two boards/frames. Tie the press tightly and evenly with ropes or straps.

Drying

After collection and pressing, the next step in preserving a specimen is to make sure that all the moisture is removed from the plant. Any moisture remaining in a collection can result in the eventual rotting of that specimen, rendering it useless for scientific purposes. In a herbarium, plants are dried in a forced-air plant drier that approaches temperatures of 100°C. Presses are placed in the drier in such a manner that the hot air can be blown up through the cardboard corrugates to help dry the plants more evenly. In modifying this for home use, plants can be kept in the press and stored in a hot and dry location, such as a sunny spot, attic, garage, or car trunk. Specimens that are not particularly fleshy usually dry within 5-7 days. You may need to replace the absorbent paper every few days for fleshier plants. Once all the water is removed, the plant will last indefinitely. Some plants will require more consideration when drying, such as cacti and other succulent plants. Particularly fleshy plants might best be preserved after being cut longitudinally or transversely, and inner tissue may need to be scooped out.

-

Plant Identification

Multiple plant identification books are available for use at local libraries, for purchase at bookstores, or for use in the BRIT library. Try to find a book that uses an illustrated glossary to assist in defining terms you might encounter when using the dichotomous key to identify your collection. It is always helpful to use a book that includes line illustrations if not images of plants. Make sure the text you are using is both relevant and current to your geographic area.

Depending on the part of the world in which you are collecting, there may be fewer texts to assist you in identification. If you can narrow down the identification of the plant, this may assist you in locating a botanist who can help you identify it. For example, if you have identified your plant as a fern from the Peruvian Amazon, this will indicate you ought to find a botanist who has some knowledge of the ferns of South America. A survey of the literature may assist you in locating such an expert. Botanical experts often receive emailed photographs, and while they can sometimes identify the plant from images alone, the physical specimen is usually required for definitive identification. Common practice is to send the plant specimen as a gift to the herbarium with which the expert is associated, only after contact has been established with the expert. Local herbaria can be particularly useful in providing connections to local botanists who can also assist with identification.

Note that plant identification requires that you have as much of the plant as possible, and in some occasions, this cannot be accomplished if you are dealing with a sterile specimen (that is, a specimen lacking either fruits or flowers).

Some suggestions for plant identification texts for the north central Texas area are:

Ajilvsgi, Geyata (2002). Wildflowers of Texas. ISBN:0940672731 (a color field guide to common wildflowers of the area).

Diggs, G., B. Lipscomb, R. O’Kennon (1999). Shinners & Mahler’s Illustrated Flora of North Central Texas. (A comprehensive plant identification text for the stated area, including dichotomous keys and line illustrations for all native and naturalized plants).

Diggs, G., B. Lipscomb, M. Reed, R. O’Kennon (2006). Shinners & Mahler’s Illustrated Flora of East Texas, Volume 1. (The book covers all the native and naturalized ferns and similar plants, gymnosperms, and monocotyledons known to occur in East Texas, including dichotomous keys, line illustrations, and Texas distribution maps for all species).

Identify my Plant

The BRIT herbarium will identify plant specimens as a public service, with no individual to receive more than 30 identifications in a single calendar year, nor more than 10 at any single visit. If you require plant identification for commercial purposes, please see our commercial guidelines and policies page.

In order to facilitate the quickest and most accurate identification of your plant, the actual plant, in fruit or flower, is needed. It is not necessary that the plant be alive and you are welcome to squash your plant between pieces of cardboard to mail to us. Please contact the herbarium before mailing any material to ensure that we are prepared to receive it.

Plants can sometimes be identified from digital photographs, however please be sure to include multiple pictures, including but not limited to those of:

- Close-up of flower or fruit

- Close-up of leaves

- Close-up of any other interesting characteristics

- An overall shot of the plant and the manner in which it is growing.

Along with the photograph, or plant, it is necessary to include the following important information in an email (you can copy and paste this text into the body of your email message) to us:

Plant Identification Form

Botanical Research Institute of Texas

1700 University Drive

Fort Worth, TX 76107-3400Please note:

- This identification service is offered free of charge for non-commercial requests. In exchange for identification services, in some cases we may request that specimens submitted be donated as voucher specimens for the BRIT Herbarium.

- Please limit the total number of identification requests to 10 per visit & 30 per year.

- A good specimen, for accurate identification, should include several leaves attached to a section of stem, flowers or fruits, and if possible, attached roots. Plants may be submitted fresh, or pressed and dried.

Contact Name:

Date:

Address:

Email:

Phone or Fax:Locality or address where the plant was collected:

Number of plants submitted (please see notes 1 & 2 above):Please answer the following questions to help our staff make an accurate identification.

1. Habit: tree____, shrub____, herb____, vine____, epiphyte____, aquatic____2. Habitat: city yard___ , cultivated field ___, roadside___, woods ___, wetlands___, prairie___ , other______________________________.

3. Soil (if known): loam____, clay____, rocky or gravelly ____, sandy______.

4. Environment: typically wet _____, typically dry______; sunny_____, shady________.

5. This plant was wild_____, cultivated________, unknown_________.

6. If a section of the plant is being submitted, please estimate the size of the whole plant_______.

7. Abundance of plant at the site was: single______, few______, abundant_______.

8. Additional comments or information requests: _______________________________________

-

Mounting Your Plant Collections

Mounting a collection on heavy cardstock provides the plant specimen with the physical support that is required to allow the specimen to be continually handled and stored with a minimum of damage. Use acid-free paper of good quality (100% cotton rag is used in the herbarium). Elmer’s glue works well because it is of near-archival quality. The label is always glued down first in the lower right-hand corner. Determine which side of the dried plant demonstrates the best characteristics and position it on the paper before applying glue. Then, turn it over and outline the edges of all parts with a thin stream of glue. Turn the plant back over and carefully place it on the paper, blotting up excess glue as you gently press it to the paper. Any pieces of plant that become detached should be placed in a paper envelope glued to the sheet (often called a “fragment pack”). Place a sheet of wax paper over the entire specimen, and then place weights or heavy books on top of the specimen until the glue dries.

-

Herbarium specimens will last for hundreds of years if properly cared for. The best conditions for storage include low temperature (from 50–65ºF), low humidity, low light, and infrequent handling. Roaches and certain beetles will destroy plant specimens. You can kill insects in dried plant specimens by freezing them for three or four days, and keep them pest-free in a tightly-sealed plastic bag. There are various ways to achieve these conditions. In a herbarium, plants are stored in folders within airtight cabinets. Any dried plant material is frozen before entering the herbarium, and the space is periodically treated with a pyrethrin spray (an organic insecticide made from chrysanthemums). In the BRIT herbarium, plants are organized alphabetically by the plant family to which they belong, then by the genus, then by geographic area and the species to which they belong. This organization facilitates the use of the herbarium by researchers and the public. You may view an excerpt about how we file specimens in the BRIT herbarium in the appendix.

More from the Herbarium

Carousel items

-

Herbarium Curation Projects

-

Herbarium Digitization

-

Acquisitions, Loans, and Exchanges

-

Plant Identification

-

Armchair Botanist

-

Policies for Use of the Herbarium

-

Growth of the BRIT Herbarium Collections