Librarian Lens: Plant Discovery In the Southern Philippines Expedition Two

My first introduction to an herbarium was at the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium at New York Botanical Garden. At the time, I was working on my master’s thesis in fine art in New York City. Research had brought me to the herbarium and as soon as I saw the rows upon rows of cabinets filled with plant specimens from all over the world, I knew I was entering a field that I would never want to leave.

Over the past eight years, I have had the privilege to work with several herbaria and botanical libraries, which have included the Steere Herbarium as well as the LuEsther T. Mertz Library, both at New York Botanical Garden (NY), the Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden Herbarium and Library (RSA), and most recently, as the BRIT Librarian, the wonderful Library and Herbarium collections here at BRIT. Over the years, I have also had the chance to visit a number of botanical collections, including the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (MNHN) in Paris, Kew Herbarium & Library at the Royal Botanic Garden in Richmond, London, and the Harvard University Herbaria and Libraries. Likewise, prior to coming to BRIT, I have been instrumental to a number of National Science Foundation and Andrew W. Mellon Foundation funded natural history collection projects such as The Global Plants Initiative (NY), The Plants of the Caribbean (NY), and Engaging Our Future To Preserve Our Past; Collections in Support of Biological Research (RSA).

In this time, while seeing and working with these collections, I have developed a fascination for the research practice of collecting plant specimens in the field; a valuable type of knowledge production and the very foundation of botany, which gives rise to a welter of collection materials all of which are part of a complex life cycle of research. The diversity of specimens collected while in the field, the variety of preservation methods used, as well as the range of records generated through observing biological phenomena illustrate the richly heterogenous nature of botanical field research. In working with these collection records through the years, I had come to understand field research very well, never ceasing to be intrigued with the interconnected nature of the records, though I had yet to experience field collecting firsthand.

When the opportunity to join the National Science Foundation funded Plant Discovery In the Southern Philippines project on their second expedition to the Philippines became available, I immediately expressed an interest and it was agreed that by drawing on my academic background in photography (MFA), I would be an asset to the expedition as a much needed field photographer.

Upon arrival on the island of Negros, we stayed in a hotel in the city of Dumaguete the first couple of nights as we prepared for the field. With it being early December 2019, the city was decorated for the holidays, and our hotel was just off of a city square, which looked very festive with brilliant lights along the trees and vegetation in the park. Parades through the streets were a central part of the holiday celebration, which continued through the entire month.

Our first expedition site was Balinsasayao Twin Lakes National Park, which is in the province of Negros Oriental. Two adjacent crater lakes in the center of the park: Lake Balinsasayao and Lake Danao, are surrounded by four mountains: Mount Guintabon, Mount Balinsasayao, Mount Kalbasaan, and Mount Mahungot. Field collections were done over five days by eight teams: two vascular plant teams, two fern teams, two bryophyte teams, and two lichen teams. Each team consisted of one lead botanist, three to four graduate students assisting with collecting, pressing, photographing, recording data, and DNA samples for plant specimens, as well as two guides geographically knowledgeable about the area as well as the local flora.

The collecting team that I was on for the duration of the expedition was Seed Plants 1, which was one of the vascular plant teams. The lead botanist was Peter W. Fritsch, I was the photographer, three graduate students assisted with collecting, pressing, data recording, and DNA samples, and then two guides. As a group, we could not have worked better together. All of the necessary field collecting tasks require coordination between each group member and from the very first day, we always anticipated each other well. Likewise, by being part of this team, it allowed me to witness a valuable type of knowledge sharing between Peter and the graduate students. The dialogue between them while collecting was always one of curiosity, discovery, and learning about the local flora.

Following our time at Balinsasayao, we briefly returned to our hotel in Dumaguete City to pick up supplies. This was followed by traveling to our second site of collection, which was Cuernos de Negros in the province of Negros Oriental, where we stayed for six days. Cuernos de Negros is volcanic in origin, also referred to as Mount Talinis, with an elevation at approximately 6,200 ft. Of all of the sites that we visited, this was by far my favorite. While we were there, we experienced high winds with varying precipitation (mist, fog, drizzle, rain, and deluge). The eight teams collected in various places along and below several ridges as well as descending down to collect further into the forest and beside streams.

In addition to collecting in the field, a crucial component of this trip was also checking on those specimens that were collected during the expedition one trip in June 2019. All specimens collected over the course of the five-year survey project are initially housed in the herbarium at Central Mindanao University, a collaborating partner institution on the project where many of the project graduate students are enrolled and where three of the Pteridologists, botanists specializing in ferns, are faculty in the biology department.

We traveled to Central Mindanao University following our time at Cuernos de Negros. While other botanists organized their collections, Peter and I, as well as a couple graduate students, spent the next week in the herbarium sorting and sequencing the specimen collections from expedition one. Over the summer semester, the expedition one specimens had been dried using four upright specimen dryers, which is exactly what the recently collected expedition two specimens needed. Prior to loading the specimens into the dryers, they were carefully pressed between newspaper and securely bundled with cardboard.

Our final field location was in Marilog District, Davao City. Here we stayed at the Lawi Lawi Guest House for four nights with several relatively rainy days during which time we collected throughout the surrounding area. On particularly wet days with intermittent downpours, we often “bagged and dragged” the specimens once collected. This meant that instead of doing the data collecting, pressing, photographing, and DNA samples in the rain while in the field, we collected the plants, then placed them in large bags, and carried them back to camp. Once back at camp, setting up under cover, we finished properly processing the specimen collections (data recording, pressing, photographing, and sampling). This often meant that we worked late into the evening (up until dinner and continuing afterward) to finish.

On our last afternoon of collecting, we stopped at a small open air café that was situated among the trees along the side of the road and ate homemade Buko pie, which is a type of creamy coconut meat pie, native senorita bananas (Musa acuminata), as well as fresh blue ternate tea, also called butterfly pea tea (Clitoria ternatea).

In our final days of the trip, we returned to CMU and while most of the botanists worked on boxing up their collections, Peter and I focused on finishing processing the expedition one collections. We had far too much to do in the remaining time that we had, though with the help of many of the graduate students, we were able to sequence and divide the duplicate specimens so that they could be sent to the appropriate partnering institutions.

By being part of expedition two of the Plant Discovery In the Southern Philippines project, it allowed me to not only contribute valuable field photographs to the project, it also provided an invaluable opportunity to participate in the practice of field collecting for the very first time, to witness a part of the research life cycle that I had never before seen. For years I have been studying and working with field collection materials; the records generated through the practice of field collecting, though through engaging in that practice, it extended and expanded my understanding of field research.

Part of why field collection records are important and why I find them interesting is that each type of field collection material, whether field photographs, field notes, maps, or specimens, is additive data, providing different information, which, when taken together, gives a more complete and accurate understanding of the collection event. Information in field notes, data sheets, and notebooks provide necessary data to process and digitize plant specimens. Metadata on field photographs, slides, and microscope slides furnishes further information about the specimen. The field photograph allows researchers to examine the habit as well as the habitat of the plant before collection. Each method used for preserving specimens, whether herbarium sheet, fluid preserved, or microscope slide, captures important characteristics of the plant. Housed across BRIT Library and Herbarium, field collection records allows us to reconstruct field research throughout time and geographical regions.

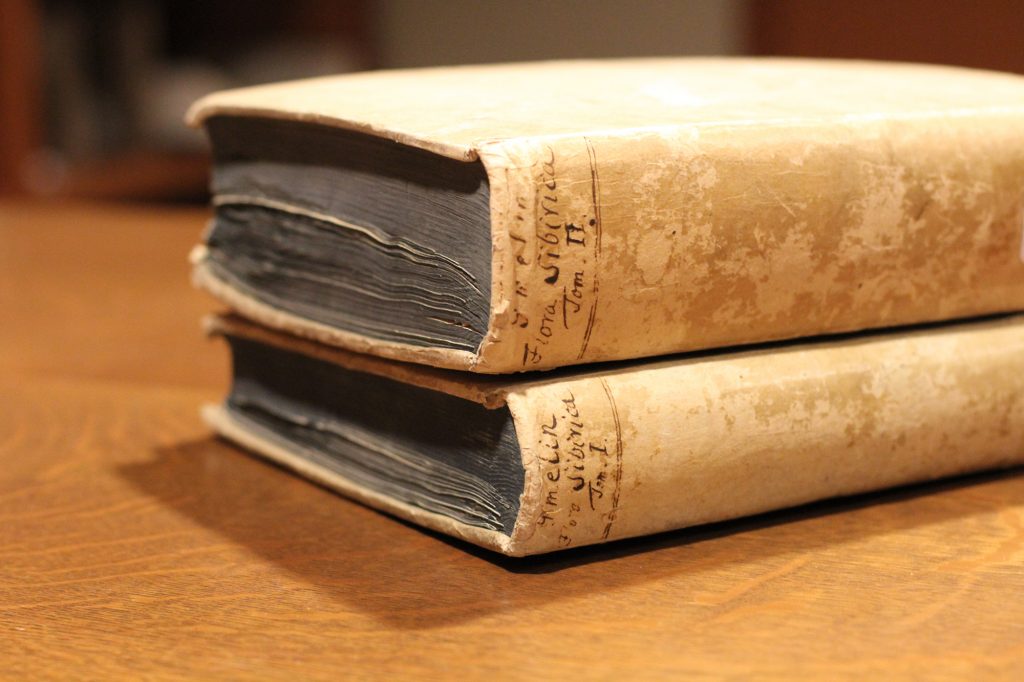

With botanical libraries and herbaria, knowledge sharing about collection material is very much driven by an understanding of the distinct interlinked nature of these two types of collections. This interlinked quality is precisely why I became a botanical librarian and specifically what drew me to BRIT Library. The Library and Herbarium’s ever-growing collections house thousands of field collection records from research conducted throughout Texas and around the world. And while these two collections invite marveling at their many uncommon treasures, they are much more entwined than most realize.

Plant Discovery in the Southern Philippines Library Exhibition

Plant Discovery in the Southern Philippines, NSF DEB-1754667 and 1754697. https://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/showAward?AWD_ID=1754697&HistoricalAwards=false