Honoring Black Botanists and Horticulturists

African Americans have shaped the landscape of the United States with their hands–revering land and resisting oppression through the development of innovative horticultural techniques and an unwavering commitment to lift up others in the Black community. This blog post explores some of the remarkable plants, practices, and people from the African diaspora.

Enslaved people’s gardens

To supplement the limited food rations given to them by their enslavers, antebellum-era African Americans in the South grew fruit and vegetable crops in their own gardens, which food anthropologist Debra Freeman coins as “Black Gardens.” The plants cultivated in these gardens varied by location and depended on which fruits and seeds were readily available. As African Americans were forced to labor throughout the day, they tended to their gardens at night by moonlight or firelight or on Sundays, when they usually had the day off. These gardens increased morale and provided their gardeners with a sense of autonomy–sometimes yielding surpluses that were sometimes sold at market for profit.

Modern-day enslaved people’s gardens have sprouted up to pay homage to the resilience of their former keepers. Culinary historian Michael Twitty developed the Sankofa Heritage Garden in Colonial Williamsburg in tandem with Eve Otmar, the site’s historic gardener, and Robert Watson, interpreter. There, Michael recreates the experiences of his ancestors by wearing historical garb, cooking foods grown in the garden over open flame, and gardening at night. Twitty’s grandfather was the founder of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, “a co-op that provided poor Black farmers with monetary relief and mutual aid.” In Michael Twitty’s award-winning book The Cooking Gene, he quotes his grandfather saying to him: “I picked cotton so you could pick up a book.”

Swept yards

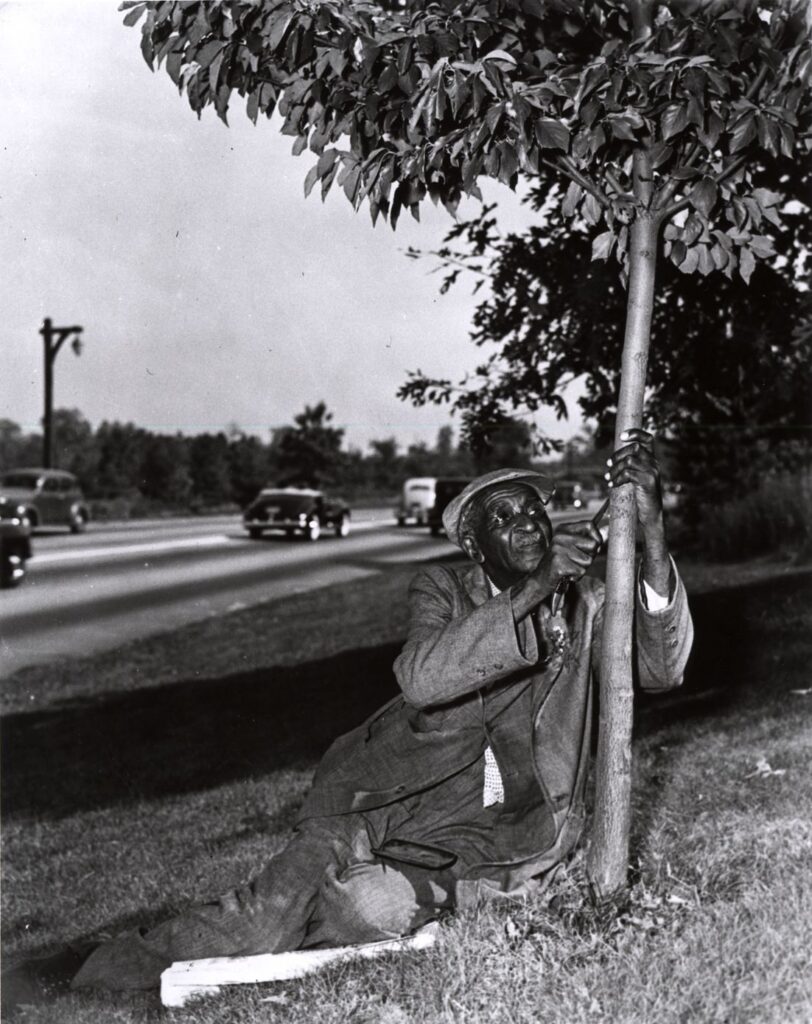

Swept yards are a landscape design practice originally from West Africa and carried over to the Caribbean and the southern United States by Africans in bondage. This form of landscaping was widely adopted during times of slavery and exists to this day, though the usage of swept yards has waned over time. Yard sweepers cleared away debris and vegetation around the perimeter of a house or building, effectively compacting the ground such that the dirt resembled cement. Fewer flammable materials in the midst meant fewer accidental fires from stray embers, which was important as these yard spaces served as multipurpose outdoor living spaces where play, eating and cooking, socializing, and clothes washing and ironing took place. The barrenness of swept yards also revealed who or what was coming and going easily, keeping critters from entering homes and making it easier to catch sight of snakes to better protect children, fowl, and livestock.

Lange, Dorothea, photographer. Caroline Atwater, wife of Negro owner, has a well-swept yard. United States Orange County North Carolina, 1939. July. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017772205/.

This extension of the domestic sphere to the outdoors reflected African orientations of living in which the boundary between the inside and outside of homes was more porous. Similar to their ancestors, enslaved African Americans didn’t spend as much time inside their quarters during daylight hours; instead, they orbited the periphery of their dwellings, conducting domestic activities around the edges of their homes.

Lange, Dorothea, photographer. Caroline Atwater, wife of Negro owner, has a well-swept yard. United States Orange County North Carolina, 1939. July. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017772205/.

Brooms to carry out sweeping were often fashioned by bundling and twining together plant material from the nearby environment. Materials to create brooms included straw, sedge grass, branches from nearby trees, corn husks, and broom corn, a type of sorghum.

Wolcott, Marion Post, photographer. Children of Frederick Oliver, tenant purchase client, sweeping yard in front of new home. Summerton, South Carolina. Summerton United States South Carolina Clarendon County, 1939. June. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017801156/.

Seeds of hope

Enslaved Africans wove seeds into their hair as a means of carrying over their culinary and agricultural heritage across the Atlantic Ocean. In doing this, they were able to grow certain foods they were familiar with in unfamiliar soils.

Okra

Hailing from West Africa, okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) was brought to the Americas by enslaved Africans. In traditional medicine, it was used externally much like aloe was well as internally. Nowadays, the plant’s mucilage is used in the creation of gel tablets. Okra played a pivotal role in the development of gumbo, a stew which combines African cooking with Creole culture from the United States Gulf Coast. During the Civil War, enslaved African Americans sold okra seeds as a coffee substitute.

Black-eyed peas

A legume also from West Africa, the black-eyed pea (Vigna unguiculata) was cultivated by enslaved people in Virginia and the West Indies in the 1600s. This legume, which is more of a bean than a pea, was originally used as food for livestock, they became a staple of the slaves’ diet. During the Civil War, black-eyed peas (field peas) and corn were thus ignored by Sherman’s troops. Left behind in the fields, they became important food for the Confederate South. George Washington Carver encouraged the planting of black-eyed peas to add nitrogen back into the soil. Black-eyed peas are often prepared with ham hock and, along with collard greens and cornbread, are customarily prepared during New Year’s to bring forth good luck and prosperity. The peas are said to represent coins, collards represent paper money, and cornbread represents gold.

Collard greens

Eurasian in origin, collard greens (Brassica oleracea) took on a significance in cultivation and cuisine to the African American community. A number of theories exist on how collard greens made their way to the American South. Some believe collard seeds came from Portugal, while others believe early colonists brought them from England. The most prevalent theory posits that enslaved Africans introduced to the region, as collard greens were a staple crop in many parts of Africa.

For sustenance, the enslaved community prepared pot liquor–a vitamin and mineral-filled broth left over after boiling collard, mustard, or turnip greens, and often ham hock or turkey were added to this broth along with seasonings. Pot liquor was often consumed with cornbread, which was dipped into this nutritious vegetable stock. Pot liquor is prepared to this day.

Virginian collard connoisseur Ira Wallace has worked with Seed Savers Exchange and the cooperatively owned Southern Exposure Seed Exchange to ask the USDA for over 60 varieties of collard greens to plant in Iowa. From that project, she began a program called the Heirloom Collards Project–a coalition of farmers, seed stewards, gardeners, chefs, and seed companies dedicated to preserving heirloom collard varieties and their cultural heritage. Wallace’s motivation for this project is “to preserve diversity, to select plants that are better suited to local conditions, to save money and maintain control of our food system, and to promote self-reliance.”

Corn

Though native to Mesoamerica, corn (Zea mays) holds a special place in the Black community in its many permutations, including hoe cakes, polenta, cornbread, grits, and cornmeal for fish fry.

While not a horticulturist, Georgia Gilmore, a Black cook from Montgomery, Alabama, organized a network of women who cooked and sold meals–including cornbread–to help fund the Montgomery Bus Boycott movement.

Trailblazers in the world of plants

Wormley Hughes

Referred to by historian Abra Lee as the grandfather of Black American horticulture, Wormley Hughes (1781-1858) was the principal gardener and landscaper at Monticello, third U.S. President Thomas Jefferson’s estate in Charlottesville, Virginia. Wormley was born in 1781 at Monticello to enslaved domestic servant Betty Brown. According to Monticello.org, Hughes was likely trained by Robert Bailey–a Scottish gardener who worked at Monticello from 1794 to 1796. In Jefferson’s 1,000-foot garden, Hughes planted seeds, bulbs, trees, and flowers sent from Washington, D.C., and he spread dung in the vegetable garden as fertilizer. After Thomas Jefferson’s death on July 4, 1826, Hughes dug Jefferson’s grave at Monticello. He was informally freed by Martha Jefferson Randolph, Thomas Jefferson’s eldest child.

Harriet Tubman

Photo credit: National Park Service

While Harriet Tubman (1822-1913) is best known as an abolitionist and activist, her role as a conductor along the Underground Railroad required her to tap into nature- and plant-based skills she acquired from her father and refined over time. She and other Underground Railroad conductors relied on knowledge of their surroundings to sustain themselves and others during their ventures to freedom. To keep freedom seekers safe and undetected, Tubman knew which plants to use to soothe crying babies to sleep, and she mimicked a barred owl hoot to signal her arrival or to indicate to travelers that they could come out of hiding. During the Civil War, Tubman served as a Union nurse, curing soldiers of dysentery with concoctions made from swamp roots and herbs.

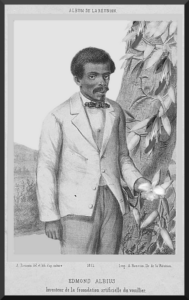

Edmond Albius

Photo credit: Ambre Troizat, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Until 1841, botanists had been unable to get the vanilla plant to fruit. In the French colony of Réunion, a 12-year-old enslaved boy named Edmond Albius (1829-1880) showed his owner two vanilla beans hanging from a vine, explaining how he developed a hand-pollination method that produced these fruits. Using a thin stick, he lifted part of the flower that separates the pollen from the stigma and mashed them together with this thumb. After his owner wrote to other plantation owners on the island about this cutting-edge technique, Edmond traveled from plantation to plantation to teach other enslaved individuals how to fertilize vanilla. Edmond was granted emancipation due to his invention and was given the last name “Albius,” and by 1848, all enslaved people on the island of Réunion were granted emancipation. While he gained freedom and launched the beginnings of the vanilla bean industry, Edmond didn’t financially profit from his invention and led a difficult life until his death in 1880.

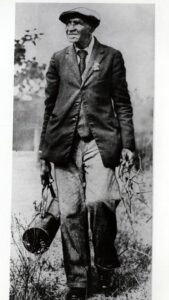

George Washington Carver

George Washington Carver, dates unknown. Photo credit: National Park Service.

George Washington Carver (1864-1943) is a name often heard during Black History Month. He gained his famed affiliation with peanuts due to his authoring of the 1917 bulletin, How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing It for Human Consumption. Carter produced 43 other bulletins teaching poor Black farmers to grow crops, promoting methods to prevent soil depletion caused by repeated cultivation of cotton. A Renaissance man, Carver originally attended Iowa State University to study art and piano, but he was encouraged by his teachers to shift to agriculture. He would go on to earn his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in agriculture from Iowa State and was the first Black faculty member at the university before being recruited by Booker T. Washington to teach at an all Black agriculture school at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

George Washington Carver, dates unknown. Photo credit: National Park Service.

David August Williston

David August Williston (1868-1962) is recognized as one of the first African American landscape architects in the United States. A graduate of Cornell University College of Agriculture, Williston is best known for designing the landscape of the Tuskegee University campus, a historically black land-grant university in Alabama founded in 1881 by Booker T. Washington. In 1930, Williston moved to Washington D.C. where he established the first Black-owned landscape architecture firm in the United States.

Marie Clark Taylor

Image credit: Jovana Andrejevic, World of Women in STEM

Born in Sharpsville, Pennsylvania, Dr. Marie Clark Taylor (1911-1990) earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Howard University and became the first African-American woman to earn a PhD in botany as well as the first woman of any race to gain a science doctorate from Fordham University. Her doctoral research dissertation was about photomorphogenesis, or the effect of light on the structure and life processes of plants. Dr. Taylor returned to her alma mater as an associate professor and eventually became Head of the Botany Department at Howard from 1947 to 1976, when she retired. Throughout her career, Taylor spread her knowledge with other educators–leading summer institutes where she guided teachers on how to use plants and microscopes in the classroom to teach concepts about cell life and other aspects of biology. Taylor led summer science series for teachers where she encouraged the use of plants in classrooms, espousing their wide availability and affordability, and she created instructional films for use in classrooms that featured biographies about notable scientists and time-lapse videos of plant growth. Howard University both named an auditorium and established a scholarship in her name to support women in the sciences.

Black to the future

Maurice Harris is a Los Angeles-based contemporary flower artist and business owner of Bloom & Plume, a floral design studio. Harris’ eye for color and eclectic combinations are reflected in his stylish arrangements and immersive plant creations. Harris hosted and executive produced the show Centerpiece, and he was one of the judges on Full Bloom, a HBO Max floral design competition series.

Based out of Atlanta, Oakland Cemetery Director of Horticulture and historian Abra Lee is honoring the stories, contributions, and achievements of African-American horticulturists who came before her for her forthcoming book, Conquer the Soil, which will be published in 2027 by Timber Press. Abra’s professional journey in ornamental horticulture began at Hartsville-Jackson Airport in 2008, where she was the Landscape Manager. When getting started in the field, she contended with imposter syndrome by looking to examples of Black horticulturists that came before her. With the guidance of her mother, a historian and teacher, she began rummaging through archives, libraries, cemetery records, and oral histories for these hidden Black horticultural figures’ stories.

David Howard, former Dallas Cowboy, working at his raised bed community garden in Stop Six, Fort Worth. Photo credit: David Howard

More locally, former Dallas Cowboys Linebacker David Howard has sown the seeds of a community garden in Fort Worth neighborhood Stop Six, an area where he and his wife raised their kids. Stop Six is considered a food desert, or an area where it is difficult to buy fresh, nutritious food. Howard strives to be this community’s greengrocer, and he currently operates a raised bed garden at 5620 Wainwright Drive and takes the garden produce to neighborhood seniors. In partnership with Oak Cliff Veggie Project, Howard is currently building out the Corner Orchard–”a no-till flower farm, food forest and ADA responsive space.” Plans for the Corner Orchard have been drawn up and are going through certification with the City of Fort Worth.

Podcasts about African American horticulture & foodways

- A Rich Spot of Earth episode: “The Gardens of Enslaved Families, Pruning”

- Setting the Table

- Black in the Garden

- Holden Forests & Gardens’ “Growing Black Roots: The Black Botanical Legacy” series

- New York Botanical Garden’s “Inside Black Botany: A Conversation with the Curators”