The Living Herbarium: A Life’s Work

Article originally published in the The Leaflet (November 2013) by Brian Witte, PhD, BRIT Research Associate

A herbarium can be as much a cabinet of mysteries as it is a repository of knowledge. Some mysteries are the results of quotidian clerical errors, simple misspellings, and the other inevitable vexations of managing a million-specimen collection. Some mysteries, however, are deeper and more gripping. In my year of volunteering and working with BRIT’s Philecology Herbarium, I have become consumed by one of the latter mysteries.

My journey began, as many do, with a walk through the stacks, scanning the unofficial storage areas atop the cabinets, looking for boxes of specimens to prepare for mounting. It’s a little-known aspect of most herbaria, but an important part of what we do is exchange specimens with other natural history collections in order to strengthen and diversify our collections. Collectors from BRIT have made expeditions to New Guinea, Peru, and Jamaica in the past decade, but the great majority of our specimens that originated outside of Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, or our collections from the Southeast and Southwest are the result of gifts or exchanges with other regional herbaria. It’s not uncommon, then, to see a box labeled “Peru” or “Rocky Mountains” or “Arkansas” each filled with an array of specimens collected sometime in the past decade and awaiting attention from the volunteer crew in the Plant Preservation Studio.

On this particular day, however, I noticed a row of 10 nearly identical boxes rather cryptically labeled NM-Fabaceae. Upon closer inspection, under layers of decayed packing tape, were over two thousand collections from 1978-1981, all made by a single botanist, all of them representatives of the pea family, all from New Mexico…and none of them identified beyond genus.

Monomania is not a condition unique to botanists, but they may be peculiarly susceptible to the lure of laser-like focus. Plants, after all, vary subtly with environmental conditions, season, and region, so detection of differences consistent enough to define a novel variety or species can require a very large sample set. Renowned scientists have built their careers on teasing apart the intricacies of leaf shape, thorn length, and petal morphology in one small group of plants.

To deepen the mystery of the New Mexico Peas, as they came to be called, no one could quite remember how they came to join the collection. The postmarks on the boxes indicated an arrival at BRIT in 2008, in the midst of a move from one building to another. There has never been a shortage of projects in the herbarium, so it was sensible to defer the massive undertaking of mounting and identifying several thousand specimens. So there they sat in their baffling sphinx-like silence, waiting, for the one person whose curiosity made him vulnerable to their allure.

For my part, I was just returning to my love of plants after a long detour through molecular science and E-bay hucksterism. I had begun volunteering at BRIT in the fall of 2012 shortly after finishing a PhD in microbiology. I had moved to Texas to be with my fiancée, and I wanted to become acquainted with the local science community, while renewing my connection to the natural world. BRIT was a perfect fit, and Amanda and Tiana gave me a study carrel and the freedom of the collection. By the springtime, I was comfortable enough to open mysterious boxes and investigate their contents.

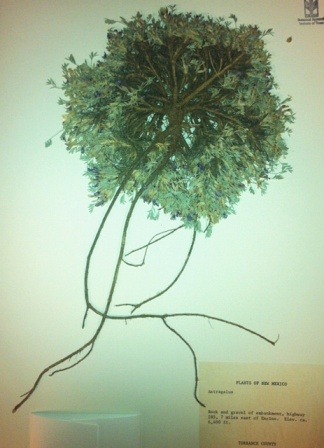

Some collectors in the grip of mania will seize on nearly any scrap of vegetation as if the act of collection were itself the object, rather than the knowledge that comes of comparing plant specimens. Even a cursory inspection, however, revealed that the New Mexico Pea collections were of exemplary quality: multiple plants, mostly complete plants collected in the prime of life, and (especially critical for the Fabaceae) with a mix of well-developed flowers and seed pods. Many of the leaf and flower characteristics in the Fabaceae are superficially quite similar – it is in the fruits that their real diversity is most apparent.

This, then, was a collection with a purpose – specimens from counties all across New Mexico, collected over a span of years, most with well-annotated labels (aside from the missing species designations). What, though, was that purpose? Further, how did they come to reside at BRIT, and who was the collector?

I could have simply reshelved those boxes and spent my time on more manageable mysteries, like identifying some of the recently donated specimens from North Central Texas. I have no special affinity for the Fabaceae, after all. I was, however, born in New Mexico. I left with my family when I was 5 years old, but I have always felt a connection to the perfect blue skies, dusty mountains, and golden aspens. My visits since then have only reaffirmed my connection. These plants came from home. It’s a small thing, but it felt necessary to bring some closure to this mystery. I was hooked.

Still, though, I wanted to know the how and why of the collection. My only clue, aside from the postmark on the boxes, was the name of the collector – Bob Hutchins. For a botanist more experienced in the flora of the region, that name might have been a sufficient clue. As it was, a quick Google search didn’t turn up much, so I set to work on identifying the specimens using the most recent key to the region.

Identifying the specimens is actually the least intriguing part of the story. Now, nine months into the project, I have a helpful online guide to the most common species of Astragalus (the most diverse genus within the New Mexico Fabaceae and a particular focus of Hutchins’ enthusiasm), published by the rangeland science program at New Mexico State University. I have Barneby’s 1964 Atlas of North American Astragalus, published in two volumes by the New York Botanical Garden and covering all 556 species and varieties then known, in loving and exhaustive, if unillustrated, detail. Most helpfully, I have the Flora Neomexicana, self-published by Allred and Ivey in 2012, and A Flora of New Mexico from 1980. The last book is by W.C. Martin and C.R. Hutchins.

Yes, C. Robert “Bob” Hutchins. If that clue were a snake it would’ve bit me, as my mom liked to say. A more observant person than I would have noticed the coincidence immediately. I only required a couple of months to draw the connection, and the story began, at last, to unravel. An email conversation with Dr. Tim Lowrey, the curator of the herbarium at the University of New Mexico, helped further dispel the mists.

Bob Hutchins was one and the same as the C. R. Hutchins who co-authored the first Flora of New Mexico. Not coincidentally, many of the specimens in the New Mexico Peas were collected around the time the Flora was published – 1980 – and represented his great unfinished work.

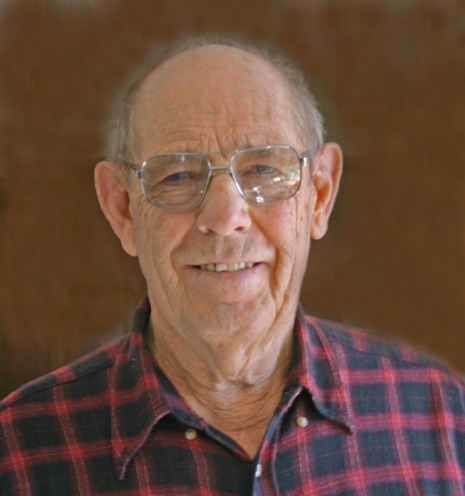

Bob was born in 1928 in Atwell, Callahan County, Texas. He lived a long and productive life. His vocation was high-school teacher and principal. His avocation was botany – a passion that led him to move his family to New Mexico where he could work on a degree at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. His advisor there was William C. Martin, the other author of A Flora of New Mexico. Together, they began work on the Flora in 1968 and continued throughout the 1970s as Bob tried to balance his work as a teacher and principal with his studies.

According to this excellent, if brief, biography, Bob was unsatisfied with the treatment of the Fabaceae in the Flora and continued his collecting expeditions into the 80s. Bob was never able to complete his revisions, though, and his remaining collections were distributed to herbaria upon his passing…in 2008. I still have not discovered how and why BRIT was selected as a recipient of Bob’s collections, but at least I know the source of his enthusiasm for such focused collection.

So here I am, a transplanted New Mexican living in Texas, trying to tie up the loose ends in the life’s work of a transplanted Texan living in New Mexico. So far, the Plant Preservation volunteers have mounted about half the remaining specimens in the New Mexico Pea collection over the past 6 months. My progress has been slower, fitting my plant ID hobby in between paying work, but I have identified approximately 200 of the approximately 2000 unknown specimens, and my rate is accelerating. I hope, eventually, to have the collection details entered into the herbarium’s database along with an estimated latitude and longitude based on Bob Hutchins’s notes. Not only will his plants have names, but Bob’s passion for mapping plant distribution will be realized in a way he could never have imagined in 1980. Then, as he traversed the rutted Forest Service roads of New Mexico, he must have imagined adding dots to a paper map – one map per species, each map repeated again and again throughout a text. Now we can create an interactive digital map, accessible from anywhere in the world, showing the location of each specimen Bob so assiduously collected and I so gratefully identified. Teamwork across time and space. What a world we live in!