And there it was, a gleaming, silvery to glittering gold and bluish iridescent, spherical spore case, spectral colors reminiscent of a rainbow, atop a stalk, hidden in the bark fissures of a living white oak tree at 60 to 80 feet (Figure 1)….

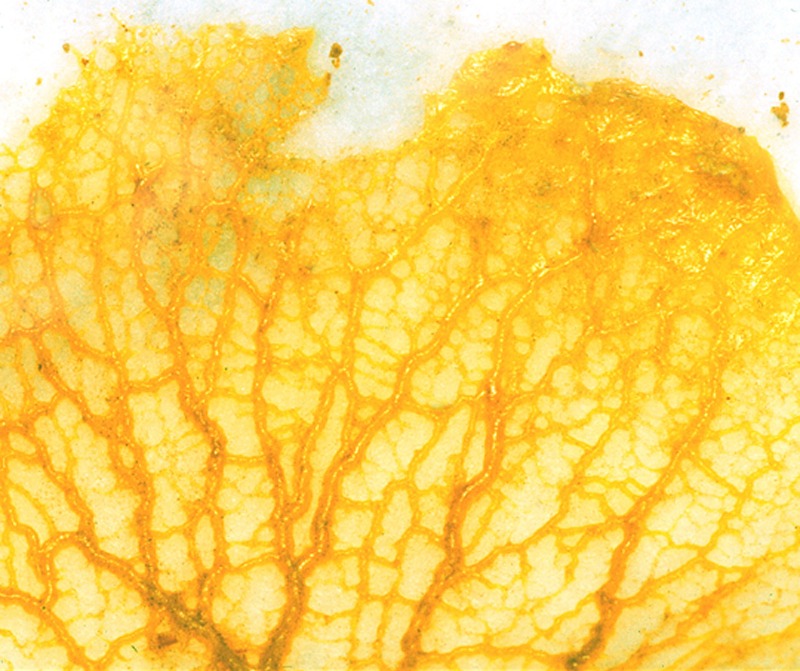

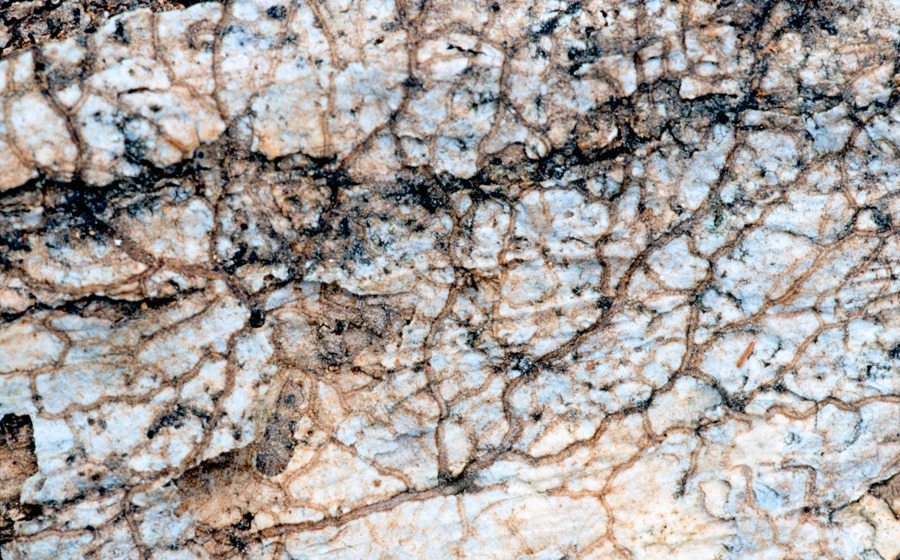

These spore-filled myxomycete fruiting bodies had developed from a jelly-like protoplasmic mass (Figure 2) that had left behind a network of vein-like paired black tracks after crawling over the bark surface feeding on microorganisms (Figure 3).

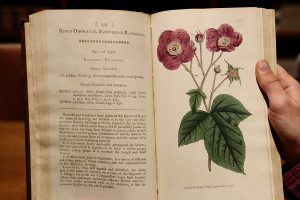

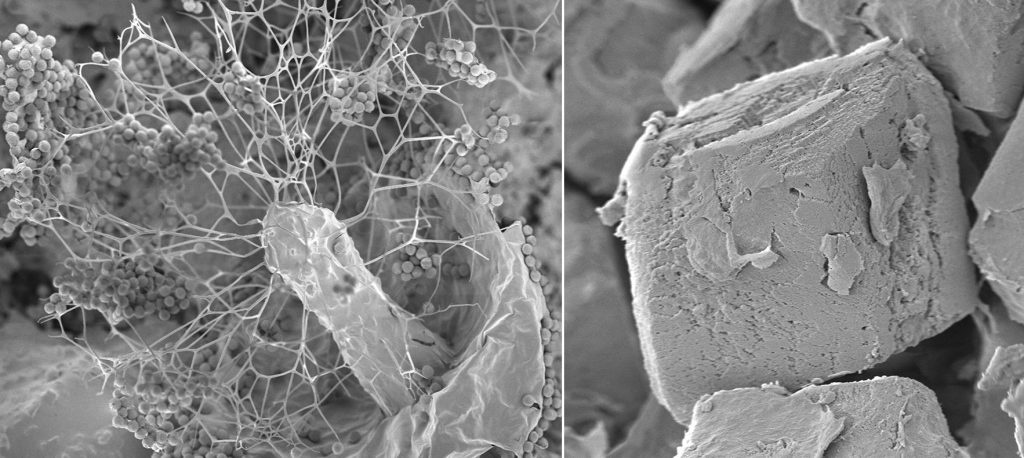

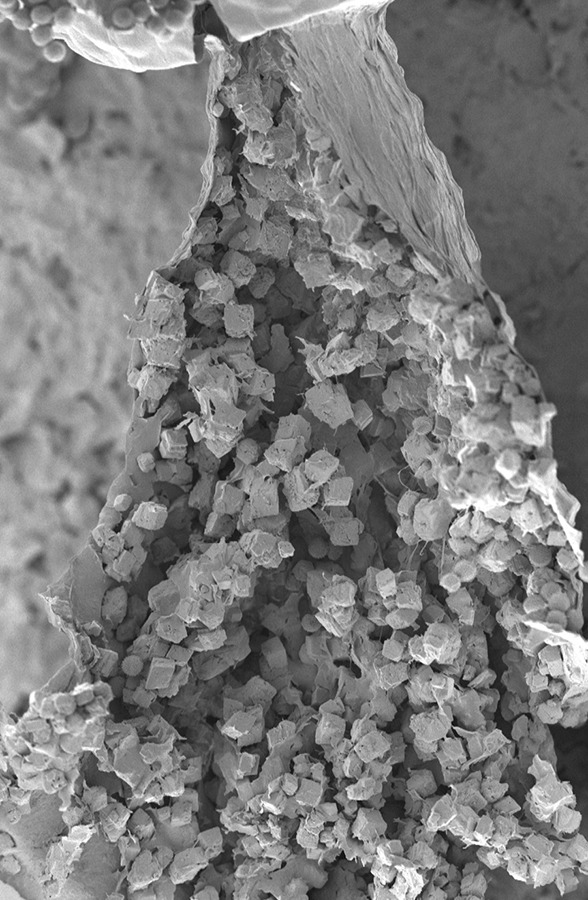

This myxomycete was barely visible to the eyes of undergraduate student Melissa Skrabal who had used the double rope climbing method to access the tree canopy (Figure 4; Kilgore et al, 2008). Her discovery upon closer microscopic examination of fruiting body structural features resulted in a set of unique characteristics (external colors, internal attachments of capillitial threads to a central columella, stalk crystals, and spore size and ornamentation, Figures 5, 6. 7) that represented a myxomycete species new to science, Diachea arboricola (Keller et al., 2004). Diachea (10 species) are all iridescent justifying the descriptive phrase “biological jewels of nature” (Keller and Everhart, 2010).

Figure 7. Diachea arboricola scanning electron micrographs. Unique individual calcium carbonate rhombohedron crystal from stalk.

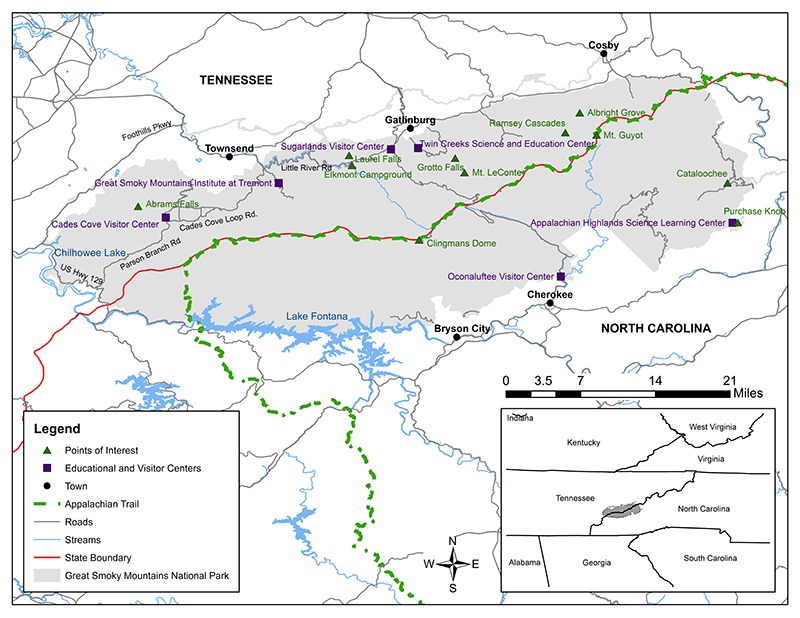

This first tree canopy research study project was part of the All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory (ATBI) conducted in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GSMNP) sponsored by a non-profit organization Discover Life in America (Figures 8, 9; Keller, 2004). A recent publication (Keller and Barfield, 2017) documents the history, geographical features, establishment of the GSMNP, and ATBI as part of the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service.

Canopy research in GSMNP included taxonomic groups represented by bryophytes, ferns, fungi, lichens, myxomycetes, myxobacteria, slugs, snails, and tardigrades (Figures 10–13). The myriad of life forms that are adapted to living in the tree canopy represent one of the last frontiers of exploration on the planet earth.

Readers interested in more details related to this study can learn more by clicking this link: http://www.fungimag.com/summer-2017-articles/Smokey%2044-64_LR.pdf

References

Keller, H.W. 2004. Tree canopy biodiversity: student research experiences in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Systematics and Geography of Plants 74: 47–65.

Keller, H.W., and S.E. Everhart. 2010. Importance of myxomycetes in biological research and teaching. Fungi 3 (1): 29–43.

Keller, H.W. and Keri M. Barfield. 2017. Great Smoky Mountains National Park: The People’s Park. Fungi 10 (2): 44–64.

Kilgore, C.M., H.W. Keller, S.E. Everhart, A.R. Scarborough, K.L. Snell, M.S. Skrabal, C. Pottorff, and J.S. Ely. 2008. Research and student experiences using the Doubled Rope Climbing Method. Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas 2 (2): 1309–1336.

Keller, H.W., M. Skrabal, U.H. Eliasson, and T.W. Gaither. 2004. Tree canopy biodiversity in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park: ecological and developmental observations of a new myxomycete species of Diachea. Mycologia 96: 537–547.