What is the origin of your interest in libraries, archives, and the Linnean Society of London specifically?

I learnt to read at an early age and always had my head in a book as a child, especially anything to do with natural history, including trying to identify plants in Cyprus using a paperback guide to British wildflowers, my first introduction to plant taxonomy and Latin names.

I started to use the Library at the Linnean Society in the late 1960s when working as Scientific Co-ordinator for the Conservation section of the International Biological Programme and collecting information on the natural history of Pacific islands for a check list, eventually published as part of a conference proceedings. The flora and fauna holdings of the Linnean Society Library were among my sources. I was elected a Fellow of the Society in 1974.

The International Biological Programme moved into a basement office at the Linnean Society of London for its closing stage of operations, for which I was Executive Secretary. It was there, in 1982, that an evening conversation with Gavin Bridson, then the Society’s Librarian and Archivist, resulted in a temporary appointment to replace him when he was offered a post as a visiting scholar at the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation in Pittsburgh. He obtained his Green Card and remained at the Hunt Institute, and my post in the Linnean Society of London became a permanent one in 1983.

What are the strengths of the Linnean Society’s Library & Archive collections?

The Library and Collections of the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) comprise specimens of plants, animals and some fossils, together with his correspondence, manuscripts and books, both by Linnaeus himself and also books from his working library, many with his annotations.

https://www.linnean.org/research-collections/linnaean-collections

They are unique and their strength lies in the way it is possible to link together information from different elements in the collection to gain a fuller understanding of provenance and the networks Linnaeus was part of. A researcher can go from correspondence sent to Linnaeus to the accompanying specimen and then see the annotated description in Linnaeus’ printed works. For example, a fish specimen may have a number which can be found in a letter sent from Alexander Garden in South Carolina to Linnaeus, with the printed diagnosis available to read in the annotated copy of Systema Naturae.

https://www.linnean.org/news/2015/04/08/8th-april-2015-the-linnaean-annotated-library

Many specimens have type status and it is those linking documents that helps to interpret their status, as shown by Charlie Jarvis in Order out of Chaos: Linnaean plant names and their types (Jarvis 2007). We are still learning about the collections from our visiting researchers, who are often able to add information from their own expertise.

https://www.linnean.org/shop/books/order-out-of-chaos

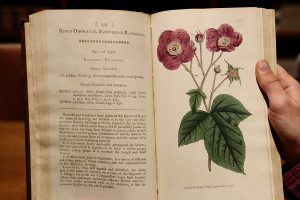

Apart from the Linnaean Collections, the Society’s rich Library holds pre-1750 printed books including early herbals, and general natural history, such as Mark Catesby’s Natural history of the Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands and Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensiumby Maria Sibylla Merian, among others.

https://www.linnean.org/research-collections/library/holdings

The main library has a broad-ranging collection of post-1750 books and journals covering all aspects of natural history, as well as a large collection of smaller “opuscula”, some being reprints, but others just small works bound together. Our early Fellows gave us copies of their own publications, or books from their own libraries. We continue to receive many donations, as well as purchasing key works such as floras and faunas. The earlier links with the International Biological Programme also resulted in strengthening our holdings in ecology, biodiversity and conservation biology and we also have a diverse collection of local UK Natural History journals.

The Collections also include the Herbarium of our Founder, Sir James Edward Smith (1759-1828), for which there are also links between specimens, manuscripts and his correspondence, giving a fuller understanding of our holdings.

https://www.linnean.org/research-collections/smith-collections

We also hold artwork, from portraits to medals, various artefacts and the Society’s own archives, together with manuscripts and correspondence from many of its early members, as well as some more recent past Fellows of the Society.

https://www.linnean.org/research-collections/other-material

The individuals represented in these collections include many of the naturalists who helped to document the way information on natural history was exchanged, and who shared that knowledge worldwide from the late 18th century onwards, such as Alfred Russel Wallace’s manuscripts journals .

http://linnean-online.org/wallace_notes.html

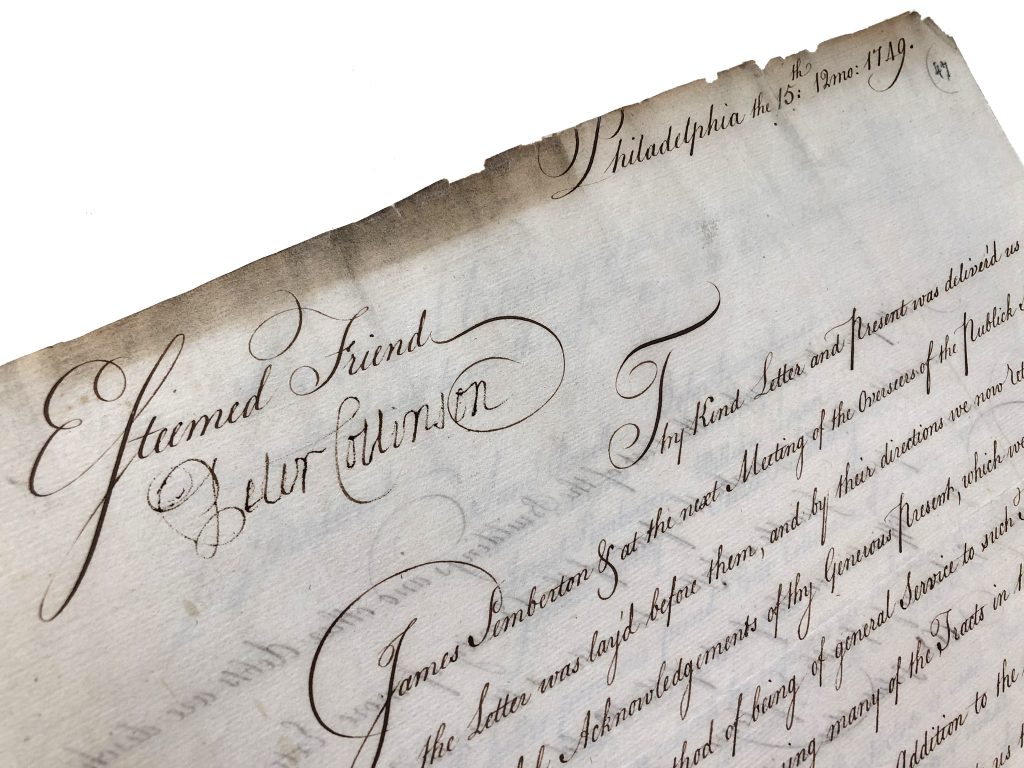

Many of these resources are now accessible online or have full catalogue records, such as this entry for Peter Collinson’s “Commonplace books”:

http://www.calmview.eu/Linnean/Record.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&id=MS%2f323a

https://www.linnean.org/news/2020/06/14/collinsons-connections

What do you find most interesting about the collections? Is there a hidden gem within the collections? What is something only you know about the collections?

The “Collections” are so diverse that it is difficult to identify any one element, but for me the most interesting thing is the way different collections link together and help in understanding the information within them. We are always finding unexpected outcomes and links between the past and present, whether it is descendant of Linnaeus visiting from Sweden, or visiting scholars delighted to find unexpected correspondence relevant to their researches.

A recent Society achievement was a grant enabling conservation work on the carpological (“economic botany”) collection, a neglected part of the Smithian Collections. The grant made it possible to link together information on specimens in the carpological collection with those in the herbarium of Smith, our Founder, and with his correspondents.It has shown that, far from being a miscellaneous collection of “oddments” that narrowly escaped disposal, these specimens do have a provenance and are revealing their stories.

https://www.linnean.org/news/2019/02/22/15-february-2019-the-carpological-collection-on-display

I try to share whatever I discover with my colleagues, but one little known fact is that J. C. Willis FRS (1868-1968) of the Dictionary of Flowering Plants (1908), also designed a diagram showing the London Underground train system, the subway. We have his non-academic archives, donated by his descendants, which include many diaries that document his travel. These include laundry lists from the hotels he stayed in, together with train timetables, travel itineraries as well as a narrative of his daily life, providing a unique social history record.

What have been the most compelling and challenging aspects of your position? What is one of the most valuable things you’ve learned through the years?

During my time working in the Linnean Society Library there have been many changes. They include moving from a card catalogue, where cards had to be printed on a Gestetner duplicator from waxed stencils (a real nightmare) and then cut by our binder, before filing in multiple places in traditional Library catalogue drawers, to first steps in an online digital catalogue and then to digitized collections. It included obtaining our first major grant to digitize the Linnaean Herbarium specimens. Subsequently, we were awarded grants for conserving and digitizing the Linnaean Correspondence, followed by similar successful projects for the Smithian Herbarium and Smithian Correspondence.

Other challenges included dealing with major structural changes to the building, which involved boxing and moving much of our archive and manuscript holdings to a temporary location while at the same time keeping them accessible to researchers, and assisting with specifications for what is now our Archive Room, then transferring those collections to their new location.

https://www.linnean.org/research-collections/archives/domestic-archives

My involvement with the creation of networks, such as the European Botanical and Horticultural Libraries group (modelled loosely on the Council for Botanical and Horticultural Libraries) helped provide contacts with colleagues in similar institutions. Meetings of EBHL members established supporting networks, especially when such visits revealed we were all dealing with similar day to day problems. The members of the Society Committee responsible for the Library and Collections (now the Collections Committee) also brought their specialist knowledge to identify solutions and were generous in sharing their time and supporting grant applications Through them and colleagues in Sweden we founded the Linnaeus Link Union Catalogue.

When I took over from Gavin, my experience had been as a reader rather than as a Librarian, and through that I was already familiar with the general layout of the Library and its holdings. Gavin’s reputation as a bibliographer and historian of natural history had led to his invitation to go to the Hunt Institute. He considered me a safe pair of hands, assuming he might return after a year, and gave me a four-week crash course before he left the UK. It included everything from cataloguing to journal accessions. I recorded those talks on a small hand-held cassette recorder, as we walked around together, with him explaining what was where and why. Those tapes have just been transferred to a digital format. They were an invaluable help and I only once had to telephone to seek information on a manuscript and its location. They still have much information on why things are in their present place, and the methodology we are often still using.

I had help initially from a part time cataloguer, who explained some aspects of that task, but for most of the time I was working alone. A team of volunteers also came in to provide help, and they were one reason for my initial temporary appointment. Gavin wanted to ensure they were looked after and retained. Volunteers have continued to play an important role in undertaking tasks that would otherwise never be done and are still important as shown in a recent blog by a current volunteer, who worked on cataloguing our miscellaneous correspondence. My role is now also that of a volunteer.

https://www.linnean.org/news/2019/12/05/volunteers-linnean-society

My first lesson was to ask for help if I did not know the answer to a reader’s request, sometimes asking them to write it down. This usually resulted in freely given information, so much so that I used to record Professor William Stearn whenever I was dealing with his library requests. The rich holdings of pre-1750 books that are not part of Linnaeus’ own collection revealed their extent when our recent Treasurer was a PhD student needing access to the works of botanists Gaspard Bauhin, Matthaeus Lobelius and Pietro Andrea Mattioli. I also attended an evening class in Swedish, which proved useful in locating items in Linnaeus’ library and manuscripts, as well as later on visits to Sweden and dealing with visitors from Sweden. A book and paper conservation class provided guidance on simple remedial measures needed to safeguard the collections as well as an understanding of binding commissions. We now have a much larger Collections team, including a Conservator as well as an Archivist, both tasks I had to deal with during my tenure as Librarian and Archivist.

In what ways have the collections grown during your time there and what is one of the ways that it is currently growing that warrants particular attention?

Both the Linnaean and Smithian Herbaria are closed collections so there are only exceptional cases where new material may be added. We were able to acquire the manuscript of Founder Smith’s journal of his continental tour, which was offered to us when our new biography of him was in process of being written. This provided the author with new insight, as the published edition omitted much key information.

https://www.linnean.org/shop/books/the-lord-treasurer-of-botany

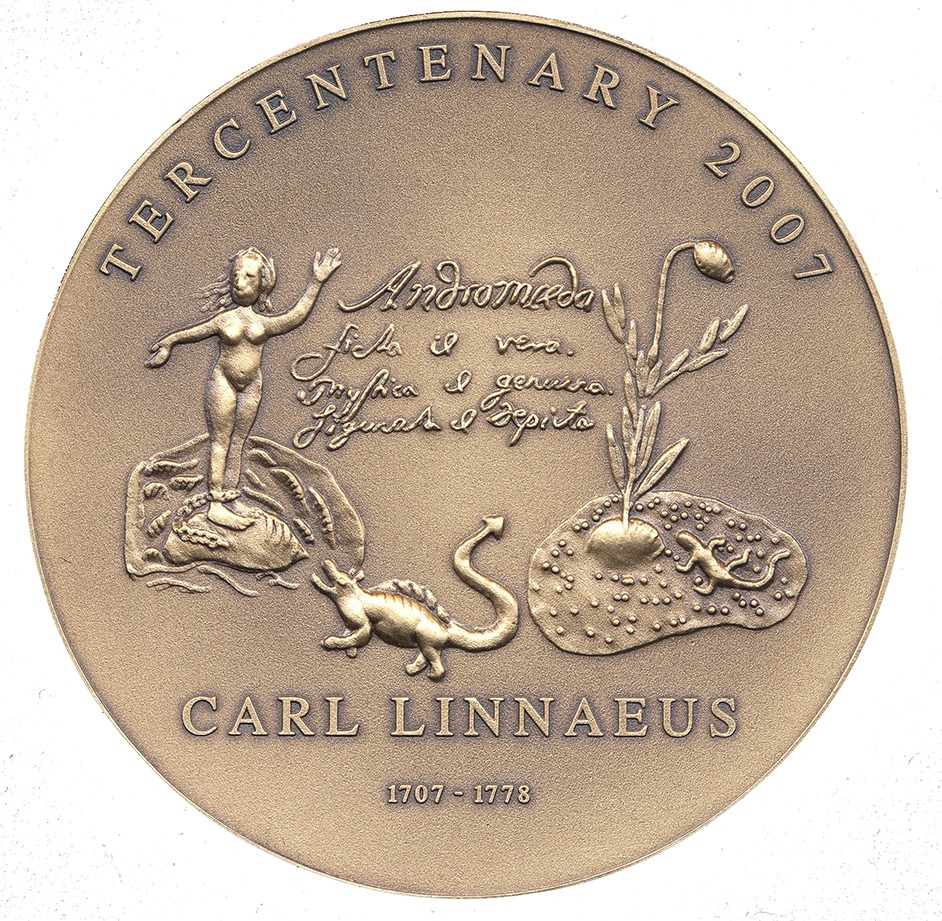

The Bicentenary of the Society in 1988 and the Linnaean Tercentenary both resulted in special gifts and opportunities to purchase special items, such as a portrait of Linnaeus in Lapland dress.

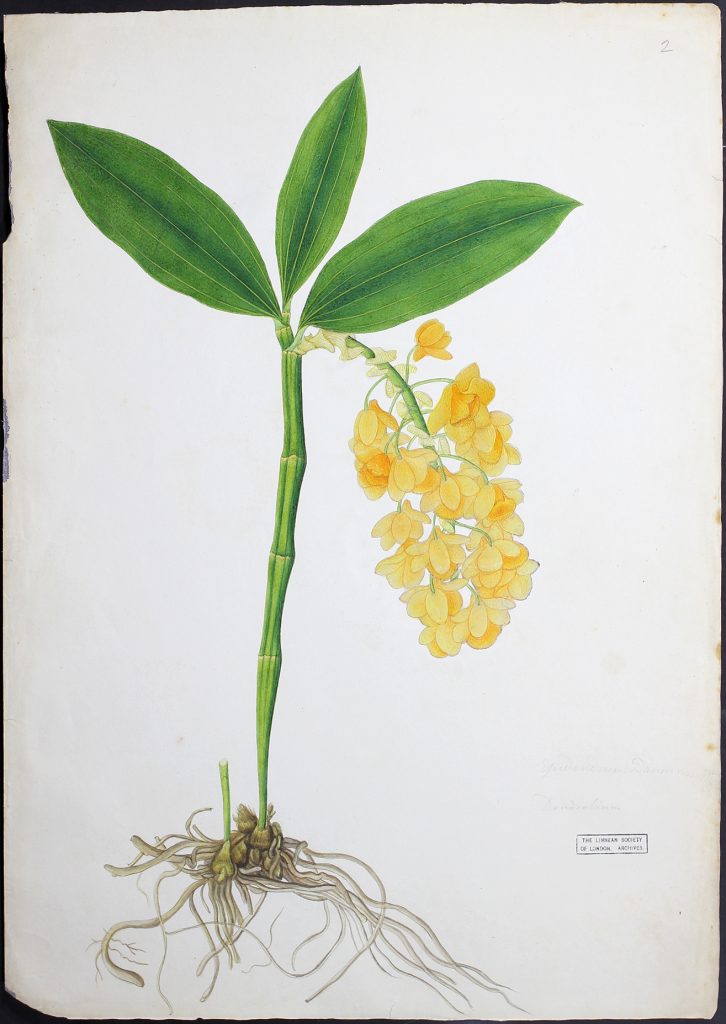

Generous support also enabled us to acquire the first accurately surveyed British maps of Nepal, made for Francis Buchanan Hamilton during his stay in Nepal in 1802-03. It complements our holdings of the beautiful botanical illustrations done by Indian artist Haludar, which we also hold.

http://linnean-online.org/buchanan_hamilton.html

We have also been able to acquire two portraits of our Founder’s wife, Pleasance Smith.

Newly created Society Medals mean we also now hold casts and maquettes for those, as well as dies for some earlier ones. I was very honored when presented with the bronze Tercentenary Medal, especially as I showed the artist, Felicity Powell, the items in the Linnaean Collections that she used for inspiration in her design.

Acquisitions of art also include donations by some of the winners of the Jill Smythies Award (given for excellence in botanical illustration).

The recent addition of the Charles Darwin Trust holdings of material on both Darwin and Wallace is part of developing our educational activities, and this is an area of growth in the Society, which is now adding multimedia material to our collections.

Our digital assets are now an essential part of the Society’s holdings, with access to the Online Collections making them freely available worldwide. Curating and maintaining those has become an essential task for the present Library and Collections team.

How is the Linnean Herbarium valuable to the collections?

It is the “heart” of the Society, but the rest of the Linnaean holdings help to understand it fully: just looking at the specimens themselves gives some answers, but the fuller story lies in the letters, manuscripts, and sometimes art, that link together and which we are lucky to have held in one place.

How are the collections helping to preserve the past, present, and future of biodiversity?

Linnaeus rightly identified the task of naming things as the key element in preserving knowledge of the natural world. Understanding and preserving biodiversity requires that taxonomic knowledge. Our Collections, which also include the Smithian Herbarium, help to do that on a daily basis, thanks to their online availability.

The Linnaeus Link project provides access to Linnaean publications through our Partner libraries. http://www.linnaeuslink.org/

We still hold determination information on the specimens in both our herbaria which has yet to become available online, a project for the future currently under discussion.

Apart from the role of the Linnaean collections, the Society has also acquired a large collection of primary sources on the history of the wildlife conservation movement, including many reports on biodiversity in its widest sense. These provide potential historical information to document changes in biodiversity as well as clarifying past decisions on wildlife conservation issues.

Where do you see botany/horticulture/natural history libraries in the future? How do you see them evolving with the times?

The move to providing online resources has widened access through the Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL) and similar platforms, but there will always be specialist material held in our botany/horticulture/natural history libraries that for some reason or another will not be available online. Better catalogues will help to make information on those available more widely, with collaborative links helping to bringing dispersed collections together to enable wider understanding of them.

One good example of the way it is now possible to exchange resources is the role that the link between CBHL and EBHL has played in helping to provide electronic access to support reader requirements in present times when physical access has not always been possible.

The availability of the BHL has transformed the way it is possible to work from home, something I experienced firsthand when Hurricane Sandy cancelled a research visit to the New York Botanical Garden’s Mertz Library. The BHL helped me to access key publications not yet available in digitized form through the Mertz Library, with additional requests being prioritized.

While recognizing the usefulness of our current digital resources, it is worth remembering that paper is much more resilient than electronic records. Files corrupt, software becomes outdated and the costs of servicing online resources can become unsupportable. Our early herbals date back to the 1490s and are still usable!

If you were given a free week with the collections, entirely extra time, what would you do?

I would work on finishing the task of documenting our nature conservation archives, a task I have been working on intermittently, but one where I have unique inside knowledge of the origins of that collection, so need to capture that knowledge in an accessible form.

http://linnean-online.org/linnaean_aw.html

Gina Douglas is the Honorary Archivist at the Linnean Society of London