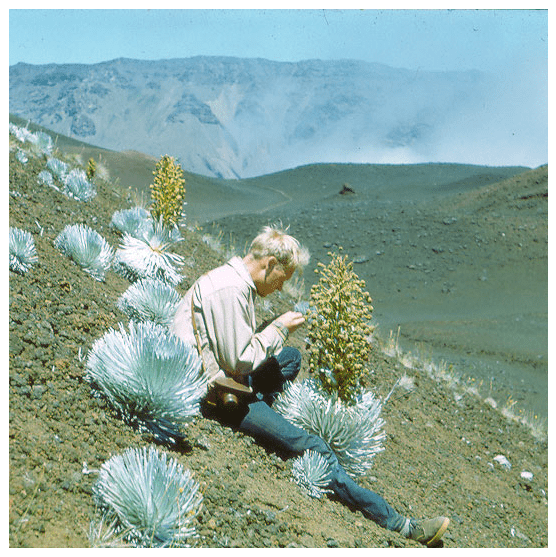

Botanist Sherwin Carlquist (1930-2021) was a legend in his field, a prolific researcher who made major contributions to plant systematics, plant anatomy, island biology and wood anatomy. While holding faculty positions at the California Botanic Garden, Claremont Graduate University, Pomona College and the University of California at Santa Barbara, he traveled the world collecting plant specimens, photographing plants in the field and collecting data about ecosystems.

Botanists seeking to mine this rich resource are fortunate that Carlquist’s archival materials are all store and and stewarded in botanic gardens. However, these materials are not found under one roof. His herbarium specimens are in the collection of California Botanic Garden, while his field notebooks and photographs are here in Fort Worth.

Librarian Ana Niño and Director of Biodiversity Informatics Jason Best hope to remove these barriers to access while creating a rich resource for scholars through a National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded project in cooperation with the California Botanic Garden. The partners received a $1 million grant not only to digitize the entire collection but also to create a new type of research tool, an extended specimen network, that will provide greater context for Carlquist’s work.

“At a basic level, the goal of the project is to digitize all the materials in the Carlquist collection,” says Niño. “Our task is to digitize the field notebooks, photographs and indices in our possession.”

But this digitization is only the start. Niño and her team will then work to link relevant data across the entire collection, creating a vast interwoven network of data that will provide context and additional meaning.

For example, a researcher could begin by examining the digitized image of plant specimen collected by Carlquist. The researcher could then study multiple photographs taken by Carlquist of the plant in the field, read the notes Carlquist wrote about the soil and weather conditions on the day he visited the site, and look at other specimens collected on the same day at the same location. The researcher could do all of this work from anywhere in the world, even half a planet away from the physical object being studied.

This sort of in-depth network of information is known as an “extended specimen network,” and Niño says it has the potential to transform digital collections. “Additional information can be linked as it comes available,” she says. “Scientists could add DNA data about the specimen, microscope images or other specimens of the same plant collected at different times by different people.”

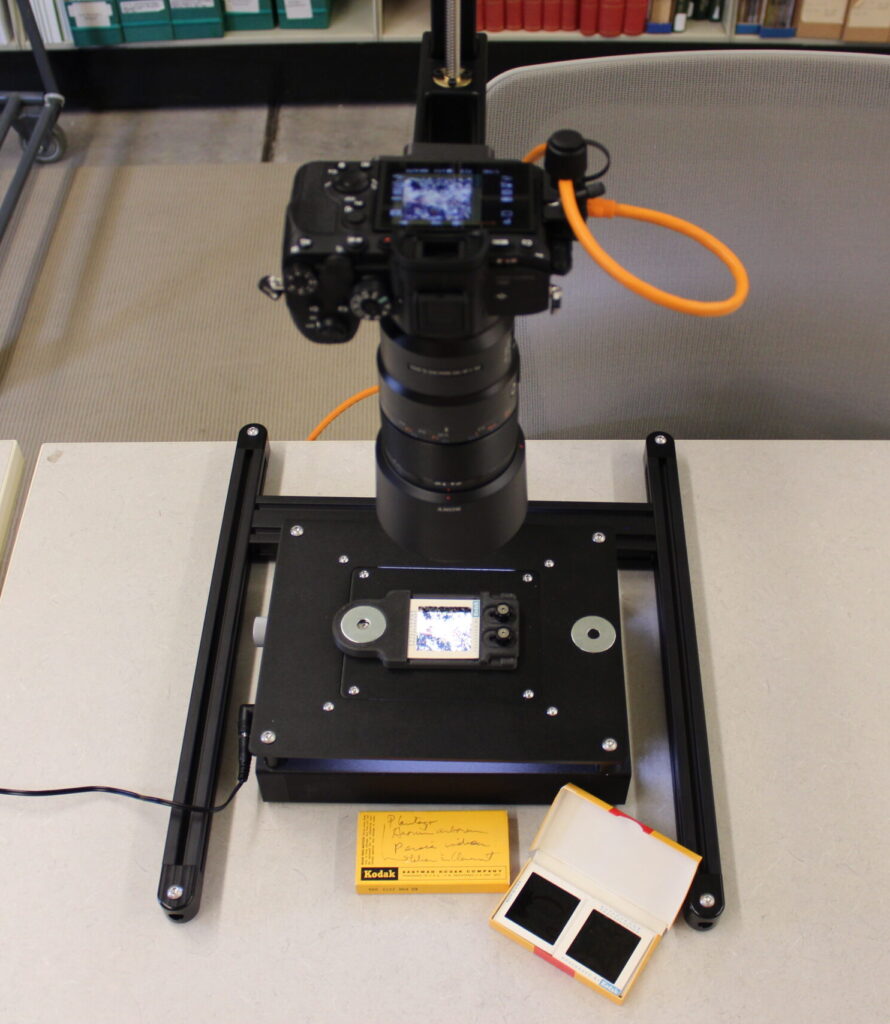

A significant amount of work remains to be done before the Carlquist project reaches this point. Niño’s team of staff and volunteers have been working out the technical challenges of scanning Carlquist’s slides, a process that needs to be both accurate and efficient, since the team has roughly 10,000 boxes of slides to work through. So far 2335 of these slide boxes have been scanned and described, although their contents remain to be imaged.

Nineteen field notebooks have also been scanned, and three of them transcribed. This has been tricky, since Carlquist’s handwriting is, according to Niño, “a fun decoding challenge.” Volunteers have fought to decipher the text, and Niño reserves particular praise for volunteer Glenn Butler, who has gotten accustomed to Carlquist’s script and its idiosyncrasies.

In fact, Niño welcomes volunteers interested in this project. She’s learned what questions she needs to ask potential volunteers before assigning them a task–high-school students, for example, often don’t know how to read cursive script, since they weren’t taught to write it in elementary school. “Maybe I should put out a call to people used to chicken scratch. Medical transcriptionists? Middle-school teachers?” laughs Niño.

The Carlquist project is scheduled to wrap up in May 2026. Niño is excited about how it will evolve and how the extended specimen network will take shape.

“The idea has been around, but this is one of the first efforts to make it a reality,” says Niño. “We’re serving as a proof of concept for the scientific community and blazing a trail.”

Note: The NSF Award number for this project is #2133562.